Nativism

Essay

While Philadelphia has not been alone in experiencing sharp undercurrents of nativism, virulent rhetoric and periodic waves of violence aimed at the foreign-born have often wracked the city. Clashes between nativists and immigrants between the 1720s and the 1920s helped to set the boundaries of the city as well as define the limits of American citizenship. A renewal of nativism in the Philadelphia region in the early twenty-first century rested upon a long history of misunderstanding and exclusion.

William Penn (1644-1718) founded Pennsylvania on principles of tolerance, and the earliest settlers of Philadelphia included English, Scots Irish, and German immigrants, among others. By the early eighteenth century, however, the influence of German-speaking peoples, settled primarily in and around Germantown, provoked the antagonism of Philadelphia’s English elites. Comprising nearly one-third of the region’s population, German voters became a vital political bloc courted by both Quaker and Anglican politicians. Germans allied politically with Quakers, who conducted business with German merchants and shared pacifist views. With their failure to sway German voters, Anglican politicians, led by William Allen (1704-1780), initiated a wave of election-day violence in 1842 to prevent Germans from voting. A large group of Anglican-affiliated sailors verbally and physically assaulted German voters, but the Quakers, with their German allies, won in a landslide.

Leading city figures, including Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), harbored some of the most virulent anti-German sentiments. In his Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Franklin argued that Germans were of inferior intellectual and biological stock. He asked, “Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a Colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our Language or Customs, any more than they can acquire our Complexion?”

After the American Revolution, Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) suggested that immigrants were unfit for citizenship because many were raised in anti-democratic, monarchical European countries. Fears of immigrants heightened in the 1790s as thousands of men, women, and children fled from the French Revolution. Philadelphia, then serving as the nation’s capital, and its surrounding region became home to a robust French community that included radicals exiled from Paris. Ironically, American officials who came to power via revolution became concerned about the revolutionary rhetoric espoused by French emigrants. In response to tensions between the French and American, and during the Quasi-War with France, the United States Congress passed the Naturalization Act of 1798 as part of the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Naturalization Act, enacted in part due to French naval attacks on American shipping lines, extended residency requirements for citizenship from five to fourteen years and barred newly arrived immigrants from voting.

Irish Catholics

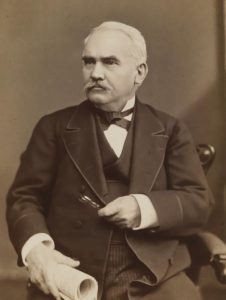

During the first half of the nineteenth century, nativism focused especially on Irish Catholics, then immigrating to the Philadelphia region in increasing numbers. In the early 1840s, Bishop Francis P. Kenrick (1797-1863) set in motion a series of events that hardened nativist sentiments in Philadelphia. Kenrick, an Irish immigrant, questioned an 1838 law that mandated the use of the King James (Protestant) Bible in public schools. In a written appeal to the Philadelphia school board, Kenrick sought to allow Catholic students to read from the Douay Bible used by Roman Catholics. While Kenrick retreated from his position after intense resistance, Protestant clergy and politicians capitalized on the Bible issue to win several elected offices, including Morton McMichael’s (1807-1879) victory as sheriff of Philadelphia. While the Bible controversy metastasized both nativist and anti-Catholic feelings, organizations such as the American Protestant Association and the American Republican Party targeted a wide range of immigrant groups, including German Americans.

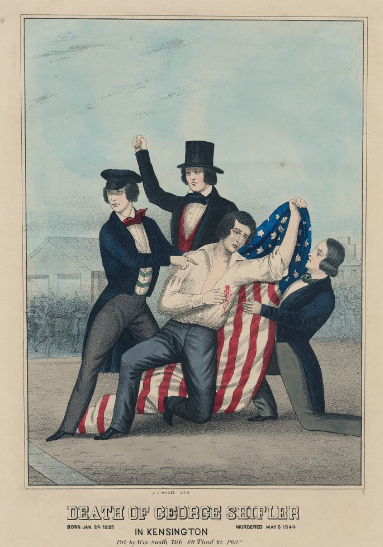

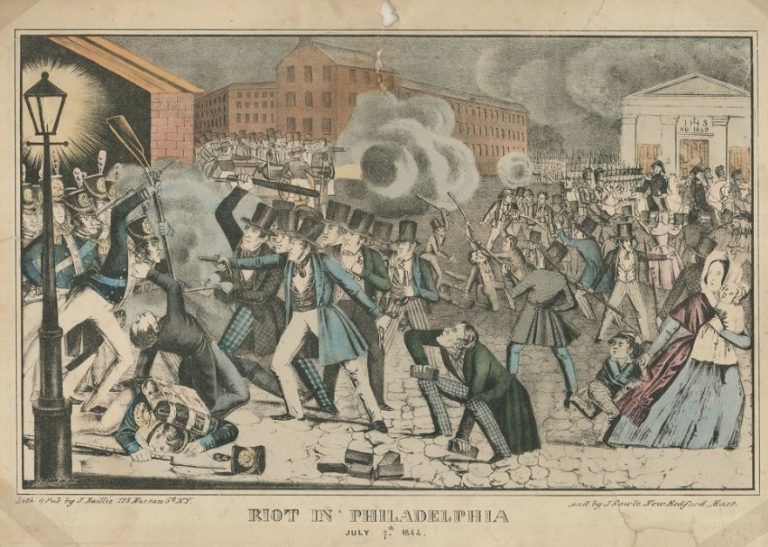

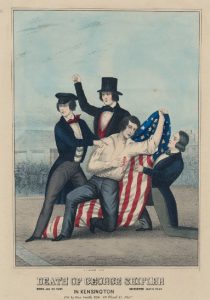

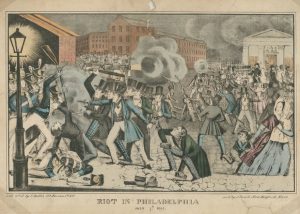

Intra-religious debates between natives and immigrants turned to violence in Philadelphia and other cities. As the Irish potato famine sent an influx of Irish men and women fleeing to the United States, native-born Philadelphians grew fearful of the masses of Catholic immigrants. Goaded by the inflammatory rhetoric of publications that stoked racialized fears, nativists violently clashed with immigrants from May to July 1844. The riots began at the Nanny Goat Market in Kensington and quickly spread across the city. Nativist rioters beat, shot, and stabbed immigrants and burned St. Augustine’s, an Irish-Catholic church at Fourth and Vine Streets. Eventually, Sheriff McMichael and Brigadier General George Cadwalader (1806-79) restored order through martial law.

In the aftermath of the riots, nativist candidates swept to significant victories in the election of 1844. Philadelphians elected Lewis C. Levin (1808-60) and John Hull Campbell (1800-68), both members of the nativist American Party, to the United States House of Representatives. Levin, the editor of the Daily Sun, became a vigorous proponent of extending the naturalization period for citizenship to twenty-one years as well as banning immigrants from holding elected office. The American Party’s success in Philadelphia politics solidified with Levin’s reelection in 1846 and 1848 as well as McMichael’s reelection as sheriff. With nativist politicians in office across the Northeast, especially in Boston and New York City, the American Party nominated Daniel Webster (1782-1852) as its candidate for president in 1852. When Webster died a few days before the election, nativists threw their support behind a Philadelphian, Jacob Broom (1808-64). Although Broom received less than 1 percent of the popular vote, he recovered to win election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1854 from Pennsylvania’s Fourth Congressional District.

Consolidation of 1854

The election of 1854 was a watershed moment for nativists in Philadelphia city politics. Samuel J. Randall (1828-90), running on the American Party ticket, won election as a city councilman while Robert T. Conrad (1810-58), a playwright and editor of The North American, was elected mayor with the backing of a coalition of the Whig Party and the Know-Nothings nativist movement. Conrad implemented the Consolidation Act of 1854, which was crafted as response to the lawlessness of the nativist riots and granted the City of Philadelphia enhanced powers while incorporating the county of Philadelphia into the city’s jurisdiction. Conrad used the patronage of his office to fill city positions, especially the Philadelphia Police Department, with his nativist supporters. Under Conrad, the city government became an instrument through which nativists could surveil and police immigrant communities.

Moreover, nativist political candidates co-opted imagery from the American Revolution for political purposes. Nativists argued that the signers of the Declaration of Independence were of virtuous stock, either native-born or born in England. Independence Hall was seen not only as the seat of power for nativist officials (who installed the city council chambers in the second floor) but also a visible symbol of American identity. In 1856, Millard Fillmore (1800-74) ran for president as the candidate of the American Party using slogans such as “Beware of Foreign Influence.” After Fillmore’s defeat, many nativists defected to the fledgling Republican Party, which actively courted the nativist vote by including anti-immigrant planks in its party platform. While many Republicans, especially abolitionists, were uncomfortable with nativist rhetoric, the party subsumed much of the nativist vote.

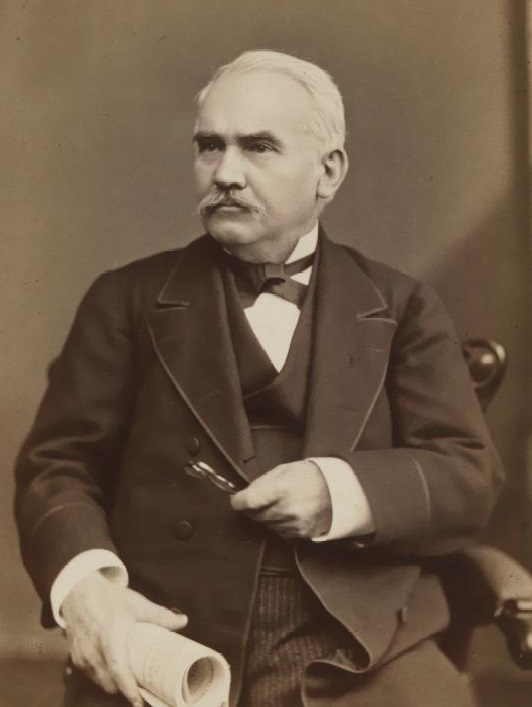

Following the Civil War, Philadelphians elected stalwart nativists to Philadelphia’s most important political offices. Samuel J. Randall (1828-90), who ran as a Democrat, was elected to the House of Representatives. Randall served in Congress for nearly twenty years and acted as Speaker of the House from 1876 to 1881. In 1866, Morton McMichael, former sheriff of Philadelphia, became the first elected Republican mayor of Philadelphia. While McMichael’s time in office was less inflammatory than his time as sheriff, he held anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant views his entire life.

Chinese Exclusion Act, 1882

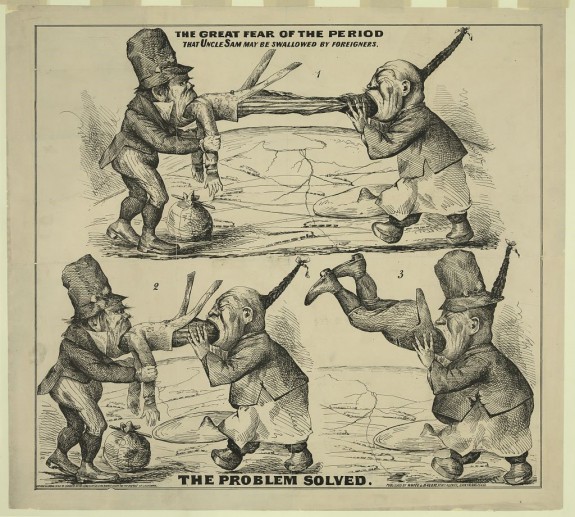

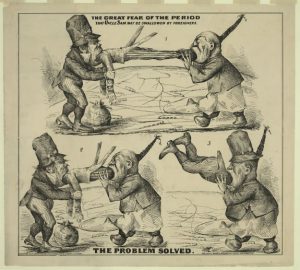

By the 1880s, nativists began to target immigrants from Asia, particularly in the western United States. The Page Act of 1875 barred Chinese women from entering the country, and in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act made all immigration from China illegal. Assaults on Asian communities drove Chinese immigrants in the West to escape to northeastern cities, including Philadelphia. A small but vibrant Chinese community formed along the 900 block of Race Street. With limited job opportunities, Chinese workers established laundries, grocery stores, and restaurants. Their shops became targets for police who periodically raided Chinatown under the guise of preventing immorality. After the Philippine-American War in 1898, the Philadelphia chapter of the American League argued that imperialism threatened to open the door to waves of Filipino immigrants.

Millions of Italians, Jews, Poles, and Slavs migrated to the United States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, generating intense fear and hatred of immigrants among many Americans. Responding to nativists who demanded limits on the number and national origins of immigrants, in 1924 Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act, which implemented a rigid quota system. By basing immigration quotas on 1880s census data, politicians slowed immigration levels until after the Second World War. Russian, Polish, and Italian immigrants were particularly targeted by the Johnson-Reed Act, which slowed immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe to a trickle. The act disrupted chain migration patterns and dislocated families who could not enter the United States as a single unit. Support of immigrant quotas undercut the popularity of Pennsylvania U.S. Senator George W. Pepper (1867-1961) among Italian Americans. Pepper lost the 1926 Republican nomination to William Vare (1867-1934), who ran on an anti-Prohibition and anti-Johnson-Reed platform.

The immigration laws of the 1920s remained in place until 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act redistributed the quota system to allow for a greater diversity of immigrants. From the mid-twentieth century into the twenty-first century, Philadelphia received increasing numbers of immigrants from South Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. In the 1990s, Philadelphia became a “sanctuary city,” preventing the deportation of undocumented immigrants who had not been charged with a crime, without a warrant. Nevertheless, while new immigrant communities carved out niches in the region’s economy and culture, nativism remained an acute issue. In 2006, Geno’s cheesesteak founder Joey Vento (1939-2011) controversially placed a sign reading “This is America When Ordering Speak English.” Despite media attention and boycotts, Vento defiantly refused to remove the sign. Following a campaign stop by Donald Trump (b. 1946), then Republican nominee for president, in fall 2016, Vento’s son, Geno Vento (b. 1971), quietly removed the sign.

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, vandals targeted mosques and Jewish cemeteries. In December 2015, a severed pig’s head was found outside the Al Aqsa Islamic Society in Kensington. Amid a national wave of anti-Semitism in early 2017, the Mount Carmel Cemetery in the Wissinoming section of Philadelphia was desecrated. In response to these ethnically motivated attacks, Muslim and Jewish activists banded together to raise funds for the restoration of holy sites. With renewed waves of violence, immigration relief organizations, such as the Nationalities Service Center and Welcoming Center for New Pennsylvanians, remained newly arrived immigrants’ best option for sound legal and employment advice.

The historical trajectory of nativism in Philadelphia paralleled that of the rest of the country. In periods of political turmoil, Americans often resorted to nativist rhetoric to defend their position in society. Despite Philadelphia’s reputation as the Cradle of Liberty and the City of Brotherly Love, at times the city repulsed its newest residents. Nativism in Philadelphia served as a reminder of the tensions between American ideals and American actions.

James Kopaczewski is a Ph.D candidate in the Department of History at Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University