Nativist Riots of 1844

Essay

In May and July 1844, Philadelphia suffered some of the bloodiest rioting of the antebellum period, as anti-immigrant mobs attacked Irish-American homes and Roman Catholic churches before being suppressed by the militia. The violence was part of a wave of riots that convulsed American cities starting in the 1830s. Yet even amid this tumult, they stand out for their duration, itself a product of nativist determination to use xenophobia for political gain. In the aftermath of the riots, shocked Philadelphians began debating new methods of maintaining order, a discussion that contributed to the consolidation of Philadelphia County in 1854.

Ethnic and religious antagonism had a long history in the city. Since the 1780s, Irish textile workers had come to Philadelphia after losing their jobs to mechanization in the British Isles. As early as 1828, when an off-duty watchman was killed after disparaging “bloody Irish transports,” Catholic presence had provoked anxiety among American- and Irish-born Protestants. In 1831, Irish Catholics battled along Fifth Street with Protestants celebrating the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne.

Anti-Catholic agitation increased in the early 1840s, organized in part around a perceived threat to the Bible in the public schools. Catholic Bishop Francis Patrick Kenrick (1796-1863), an Irish immigrant himself, objected to Protestant teachers’ leading students in singing Protestant hymns and requiring them to read from the King James Bible. Nativists used Kenrick’s complaints to gain followers. In 1842, dozens of Protestant clergymen formed the American Protestant Association to defend America from Romanism. In early 1843, editor Lewis Levin (1808-60) made the Daily Sun an organ for attacks against Catholicism and Catholic immigration, and in December of that year, he helped found a nativist political party called the American Republican Association.

Bible Reading as Flashpoint

In 1844, the Bible controversy intensified in the district of Kensington, a suburb to the northeast of Philadelphia City and home to many Irish immigrants, both Protestant and Catholic. In February, Hugh Clark (1796-1862), a Catholic school director there, suggested suspending Bible reading until the school board could devise a policy acceptable to Catholics and Protestants alike. Nativists saw this as a threat to their liberty and as a chance to mobilize voters, and they rallied by the thousands in Independence Square. On May 3, 1844 they rallied in Kensington itself but were chased away.

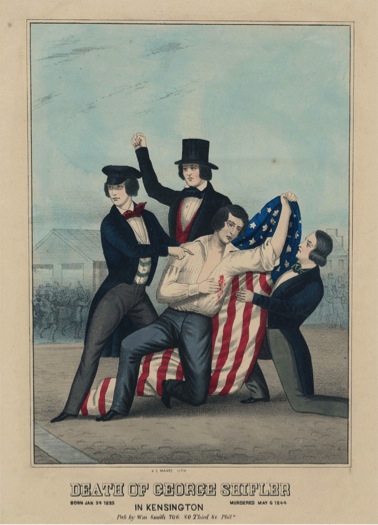

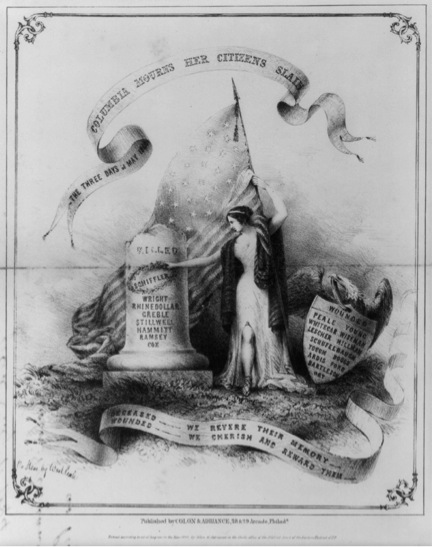

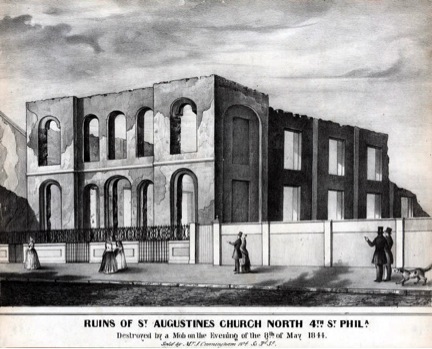

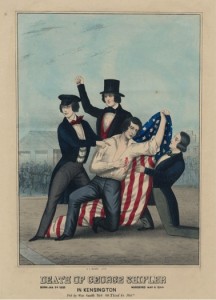

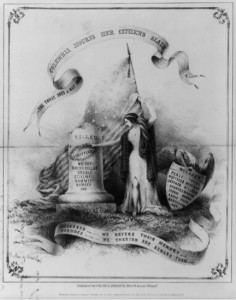

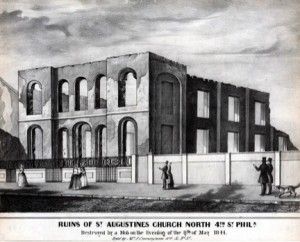

The first serious violence broke out three days later. On May 6, the nativists reassembled in Kensington, provoking another fight, during which a young nativist named George Shiffler (1825-44) was fatally shot. By day’s end, a second man—apparently a bystander—was dead, and several more nativists were wounded, two mortally. The next day, the First Brigade of the Pennsylvania Militia, commanded by Brigadier General George Cadwalader (1806-79), responded to the sheriff’s call for help. The troops faced little direct resistance, but they proved unable to stop people from starting new fires. On May 8, mobs gutted several private dwellings (including Hugh Clark’s house), a Catholic seminary, and two Catholic churches: St. Michael’s at Second Street and Master and St. Augustine’s at Fourth and Vine. Only a flood of new forces—including citizen posses, city police, militia companies arriving from other cities, and U.S. army and navy troops—ended the violence by May 10.

The city remained superficially calm for the next eight weeks, but both nativists and Catholics anticipated further violence. In Southwark—an independent district south of Philadelphia City and a seat of nativist strength—a Catholic priest’s brother began stockpiling weapons in the basement of the Church of St. Philip de Neri on Queen Street. On Friday, July 5, a crowd of thousands gathered to demand the weapons. When the crowd reassembled the following day, the sheriff requested militia troops, and Cadwalader led about two hundred into Southwark. Saturday ended without bloodshed, but the situation remained tense, with a small group of militia—some of them Irish Catholics themselves—guarding the church and a group of nativist prisoners inside it.

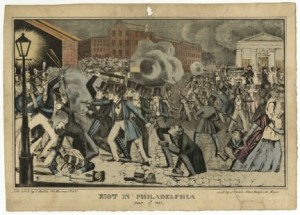

Armed Clash in Southwark

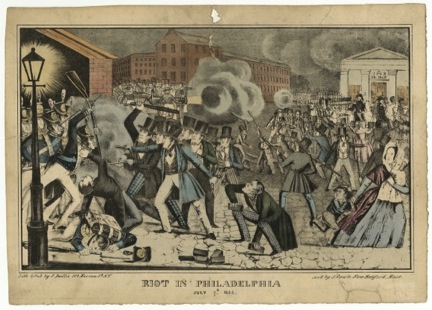

On Sunday, July 7, the crowd reassembled, and this time it armed itself with cannon. Egged on by nativist speakers, the crowd forced the militia to surrender the church and its prisoners. Cadwalader returned to Southwark about sunset at the head of a column and tried to clear the area around the church. When the crowd attacked the militia with bricks, stones, and bottles, the militia fired on them, killing at least two and wounding more. Starting around 9pm, the crowd counterattacked. For the next four hours, rioters and militia battled in the streets of Southwark, with both sides firing cannon. By morning, four militiamen and probably a dozen rioters were dead, along with many more wounded. Southwark’s aldermen negotiated the militia’s withdrawal from their district, but thousands of militia troops from other parts of the state arrived to patrol the City of Philadelphia.

Although American cities, particularly Philadelphia, had endured a surge of riots since the early 1830s, few individual riots lasted for more than a day, making the 1844 riots extreme in their severity and duration. While some of the violence had been spontaneous, the ambitions of the nativist newspapers and political party in an election year likely sustained nativist fury through the spring and summer. Though the riots were more than the simple transplantation of anti-Catholic violence from Northern Ireland, they echoed the deliberate provocation seen there.

The riots did not resolve the place of the Irish in the city. On the one hand, few Philadelphians were willing to endorse publicly the attacks on Catholics, and more than two thousand Philadelphians signed an address praising the militia’s use of “lawful force which unlawful force made necessary.” On the other hand, in the October elections, amid the heaviest turnout in Philadelphia’s history, Levin and another nativist won congressional seats and other nativists took lesser posts.

Meanwhile, Philadelphians began discussing plans for a stronger police force to deter future riots. In April 1845, the legislature passed a law requiring each major city and district of Philadelphia County to support at least one police officer for each 150 taxable inhabitants, and in 1850 it created a new Philadelphia Police District to cover the entire metropolitan area, including the outlying districts of Kensington and Southwark. Though not the sole cause, these steps contributed to the consolidation of Philadelphia County into a single government in 1854.

Zachary M. Schrag is a professor of history at George Mason University. He is at work on a book about the 1844 riots. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Chaos in the Streets: The Philadelphia Riots of 1844 (Falvey Memorial Library, Villanova University)

- Anti-Catholicism in Jacksonian Philadelphia (Philadelphia Archdiocesan Historical Research Center)

- The Kensington Riots of 1844 (PhilaPlace)

- For Teachers: Irish Immigration Unit Plan (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- City of Unbrotherly Love: Violence in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The Kensington Riots Project (Villanova University)