Nuclear Power

By Sarah Robey

Essay

Mirroring a nation-wide wave of commercial interest in nuclear power plants in the 1950s and 1960s, the Philadelphia Electric Company (PECO) and other energy companies in Greater Philadelphia jumped at the opportunity to develop relatively inexpensive electricity for the region. Nuclear power plants began servicing the region’s electrical grid in 1967. However, as was the case across the nation, planning for the Philadelphia area’s nuclear power plants often met significant resistance and concerns over public and environmental safety. Several nuclear accidents—in the region and elsewhere—contributed to ongoing public ambivalence about the region’s reactors.

Following World War II, the federal government developed civilian nuclear power technologies as an extension of wartime nuclear weapons research. Nuclear power reactors, which used the same physical reaction as in a fission-powered nuclear bomb, were promising commercial investments: although nuclear power required high start-up construction costs, it had low long-term operational costs. In 1956, federal regulators made nuclear power technologies available to public and private utility corporations.

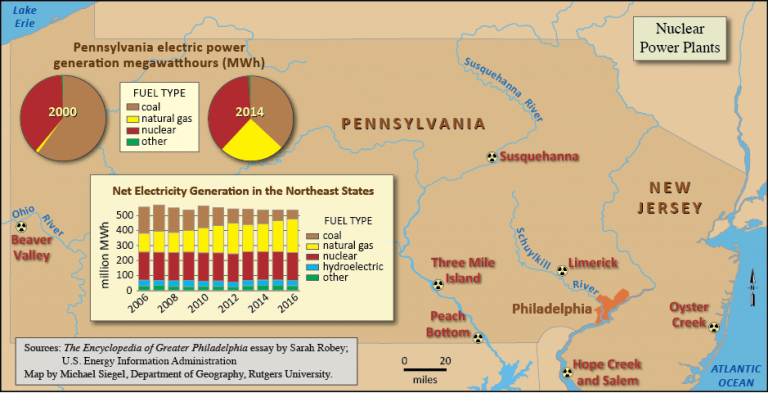

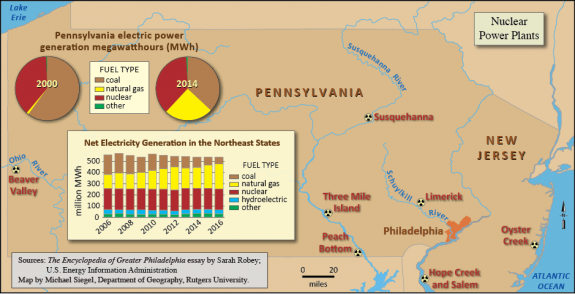

In 1967, after nearly a decade of planning, building, and certifications, PECO opened the first of three planned reactors at the Peach Bottom Nuclear Generating Station on the Susquehanna River in York County. At that time, construction was planned for several additional reactors in the region. PECO selected Limerick, Pennsylvania, about thirty miles northeast of Philadelphia, as a site for two additional reactors. Metropolitan Edison began work on two reactors on Three Mile Island, on the Susquehanna River south of Harrisburg. And Jersey Central Power and Light made plans to build a reactor at Oyster Creek, in Ocean County, New Jersey. In the next several years, it was predicted, these seven reactors—three at Peach Bottom, two at Limerick, two at Three Mile Island, and one at Oyster Creek—would generate enough electricity to power Philadelphia and the surrounding counties several times over.

Anti-Nuclear Activism

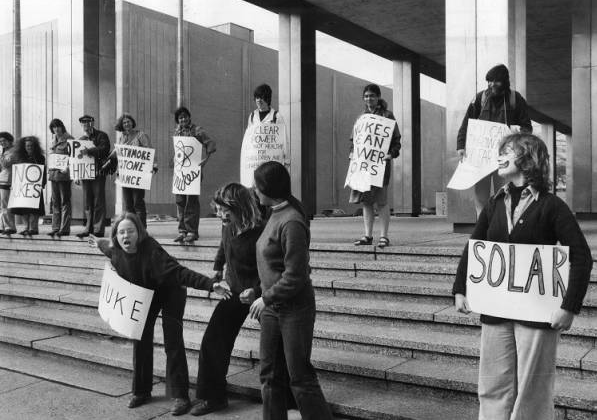

Plans to expand Greater Philadelphia’s nuclear power capacity, however, were slowed by anti-nuclear power activism in the late 1960s and 1970s. Across the nation, protests erupted in response to proposed plants. Activists cited the environmental impact of nuclear power plants, which, like many other thermal power plants, required the use of local bodies of water to regulate the plants’ temperature. Opponents of the expansion at Peach Bottom and construction of the Limerick, Three Mile Island, and Oyster Creek plants were concerned about the potential ecological consequences of local temperature increases in the Susquehanna and Schuylkill Rivers and along the New Jersey shoreline. Protesters were also deeply troubled by the possibility of radioactive contaminants escaping into the surrounding habitat. Their protests thus reflected the broader concerns of the global environmental movement.

While nuclear power protests delayed construction at some sites, during the 1970s several new reactors went online. During 1973-74, PECO replaced Peach Bottom’s original small reactor with two new reactors. In 1974, Metropolitan Edison began commercial production at Three Mile Island’s first reactor. Two years later, Public Service Electric and Gas opened the Salem Nuclear Power Plant on the Delaware Bay in Salem County, New Jersey. In 1978, Three Mile Island added a second reactor.

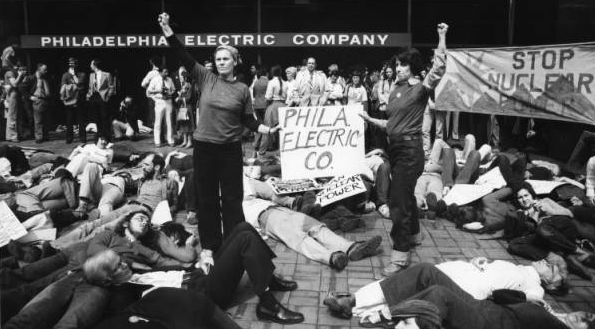

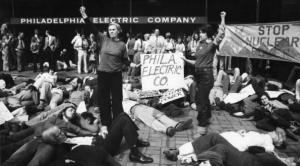

In response to what they believed to be shortsighted, runaway production, anti-nuclear power activists renewed their pressure on PECO and other local energy companies. In 1977, the Philadelphia-based pacifist organization Movement for a New Society formed the Keystone Alliance, a diverse group of antinuclear activists who coalesced around the construction of the Limerick nuclear reactors. Throughout the late 1970s, the Keystone Alliance held rallies and protests outside Philadelphia’s PECO offices and organized teach-ins, letter-writing campaigns, and marches across the region.

The movement against nuclear power gained national attention on March 28, 1979, when an operational problem at Three Mile Island initiated a partial meltdown of its second reactor. The meltdown itself was contained by the end of the day. However, the accident caused significant damage to the reactor, and it was unclear to the public for several days whether associated dangers, such as explosions and fire, had passed. As technicians worked to eliminate the dangers, officials issued voluntary evacuation recommendations to protect local residents, and the nation watched to see if the accident would escalate into a more severe emergency. By April 1, experts issued an all-clear.

Although a catastrophe at Three Mile Island was averted—later studies concluded that the radiation received by local residents was less than that of one medical X-ray—the accident added significant momentum to anti-nuclear power campaigns. As hundreds of thousands of protesters marched in cities across the country, the Keystone Alliance redoubled its efforts in Philadelphia. In 1981, the Alliance, backed by a broad coalition of residents, environmental groups, professional organizations, and politicians petitioned the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to abandon the construction of the partially-completed Limerick complex. The Keystone Alliance also later filed suit against PECO alleging misappropriation of funds for a pro-nuclear public relations campaign.

Chernobyl Affects the Debate

The Keystone Alliance delayed, but failed to halt, the construction of additional nuclear production sites in the Philadelphia region: by 1990, both Limerick reactors, two additional reactors at the Salem County complex, and two reactors in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, had gone online. However, the controversies that predated and followed the accident at Three Mile Island significantly increased public criticism of nuclear power. In the 1980s, the New Jersey-based Sea Alliance joined the ranks of the region’s anti-nuclear power groups, specifically targeting the facilities in Salem County, one of the largest nuclear power sites in the nation. Such protest organizations gained further traction as Cold War hostilities increased in the 1980s and contributed to a broad antinuclear movement that called for abolishing nuclear weapons as well as nuclear power. The April 1986 nuclear disaster at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station in Ukraine, the most severe nuclear accident in history, cemented public fears about nuclear power around the globe.

In the United States, the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl accidents contributed to increased regulatory scrutiny of nuclear power production. In 1987, the Philadelphia area’s nuclear power sites once again gained critical national attention when the NRC ordered the shutdown of the Peach Bottom power complex, citing employee misconduct, operational problems, and corporate negligence. As the national media reported, the official reprimand revealed that operators had been found asleep while on duty, among many other problems. Likewise, in the 1990s, both Salem County reactors were shut down for two years for emergency maintenance on malfunctioning systems.

After early 1990, when the second Limerick reactor began commercial production, no new reactors were added to the Philadelphia area’s electrical grid. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission and local agencies continued to oversee the scheduled maintenance, repairs, and minor accidents of the region’s aging nuclear power infrastructure. Although the region’s nuclear power plants regularly appeared in the news for such reason, after the 1980s, protest largely abated.

As the region’s environmental advocates began to demand low- and no-emissions electricity in the 1980s and 1990s, some activists began to accept nuclear power as a clean energy alternative. Although nuclear power is not strictly renewable, because it consumes fuel in the form of fissile materials, it does not release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Thus the green energy movement created some new opportunities for the nuclear power industry. However, especially in Pennsylvania, traditional segments of the energy sector, including the natural gas and coal industries, remained fierce competitors and voiced critical opposition to the growth of nuclear energy.

In the 2000s, new concerns dominated public discussions about nuclear power. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, for example, raised critical questions about the resilience and safety of nuclear power plants in the event of sabotage or attack. More importantly, the catastrophic meltdown of three reactors at the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant in eastern Japan in March 2011 once again brought nuclear power under severe public criticism in the United States. The Fukushima accident was caused by a tsunami that followed a massive earthquake, which rendered the plant’s cooling system inoperable. The meltdowns, considered the second-worst nuclear accident in history, released a great deal of radiation into the environment and required the evacuation of hundreds of thousands of residents. For Americans, Fukushima served as a stark reminder that nuclear power production could be vulnerable to natural disasters as well as human and technological error. Fortunately, during 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, the reactor at Oyster Creek in Ocean County, New Jersey, was unharmed and continued to function normally, despite severe coastal flooding.

From the time plans began in the late 1950s, nuclear power production in Greater Philadelphia was controversial. For decades, residents, politicians, and businesses struggled to balance economic motivations and energy demands with concerns about public safety and environmental risk. In 2017, nuclear production facilities generated over one-third of the electricity for both Pennsylvania and New Jersey, with nearly all of the plants located within one hundred miles of Philadelphia and in close proximity to millions of residents. The extreme tension between public safety and public benefits came to define the nuclear power industry in the region.

Sarah Robey completed her Ph.D. in history at Temple University and is an Assistant Professor of the History of Energy at Idaho State University. Her research explores American nuclear history through the lens of activism, public knowledge, and civic engagement. She has held fellowships at the Philadelphia History Museum, the National Museum of American History, and the National Air and Space Museum. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Limerick nuclear plant unit licenses extended (WHYY, October 21, 2014)

- Oyster Creek nuclear plant shuts down temporarily (WHYY, March 23, 2015)

- Oldest nuclear power plant in NJ will close (WHYY, May 11, 2016)

- Nation's oldest nuclear plant temporarily shuts down due to system problem (WHYY, November 20, 2016)

- PSE&G warns shutting down nuclear plants could mean higher electric bills (WHYY, May 1, 2017)

- South Jersey teen's love of science leads him to build nuclear fusor...in his basement (WHYY, May 12, 2017)

- Nuclear plant safety drill leads to thousands of 911 calls in New Jersey (WHYY, May 24, 2017)

- Oyster Creek, nation's oldest nuclear power plant, shutting down (WHYY, September 17, 2018)

- 40 years later, the prospect of Three Mile Island-related evacuation remains daunting (StateImpact via WHYY, March 31, 2019)

- As Three Mile Island stops producing electricity, one local community braces for change (WITF via WHYY, September 20, 2019)

Links

- The History of Nuclear Energy (pdf, Department of Energy)

- U.S. Anti-Nuclear Activists Partially Block Establishment of Nuclear Power Plant in Limerick, PA, 1977-1982 (Swarthmore College)

- US Nuclear Power Plants (Nuclear Energy Institute)

- Operating Nuclear Power Reactors (United States Nuclear Regulary Commission)

- Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

- Three Mile Island Emergency (Dickinson College)