Pennsylvania Emancipation Exposition (1913)

Essay

Held in 1913 in South Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania Emancipation Exposition marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation with events and exhibits celebrating African American progress. At a time when the African American population in Philadelphia was growing and gaining in political influence, the event’s organizers also experienced a backlash of criticism as they secured $95,000 in state funds to stage the exposition.

In Pennsylvania and elsewhere, African Americans organized state and local events to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation after Congress declined to support a national commemoration. Pennsylvania’s exposition took place at Broad Street and Oregon Avenue, then undeveloped but designated on maps as “City Plaza” (later Marconi Plaza). Three exposition buildings, including a two-story, Beaux-Arts style Administration Building designed by African American architect C. Henry Wilson II (c. 1877-?), housed exhibits, a dining room, an auditorium, and a lecture and concert hall. The Emancipation Exposition opened on September 14, 1913, with a religious congress attended by more than 5,000 people. The next day, marching bands led a parade of floats down Broad Street from Girard Avenue to the exposition grounds, a four-mile route that presented a moving pageant of floats marking African American achievements on display for the white establishment occupying the city’s office buildings, hotels, and City Hall. The exposition continued through October 4 with events including education and medical congresses, athletic contests, and musical performances. An estimated 100,000 people visited the exhibits, which stressed advancements in education and industry.

Racial Conflict

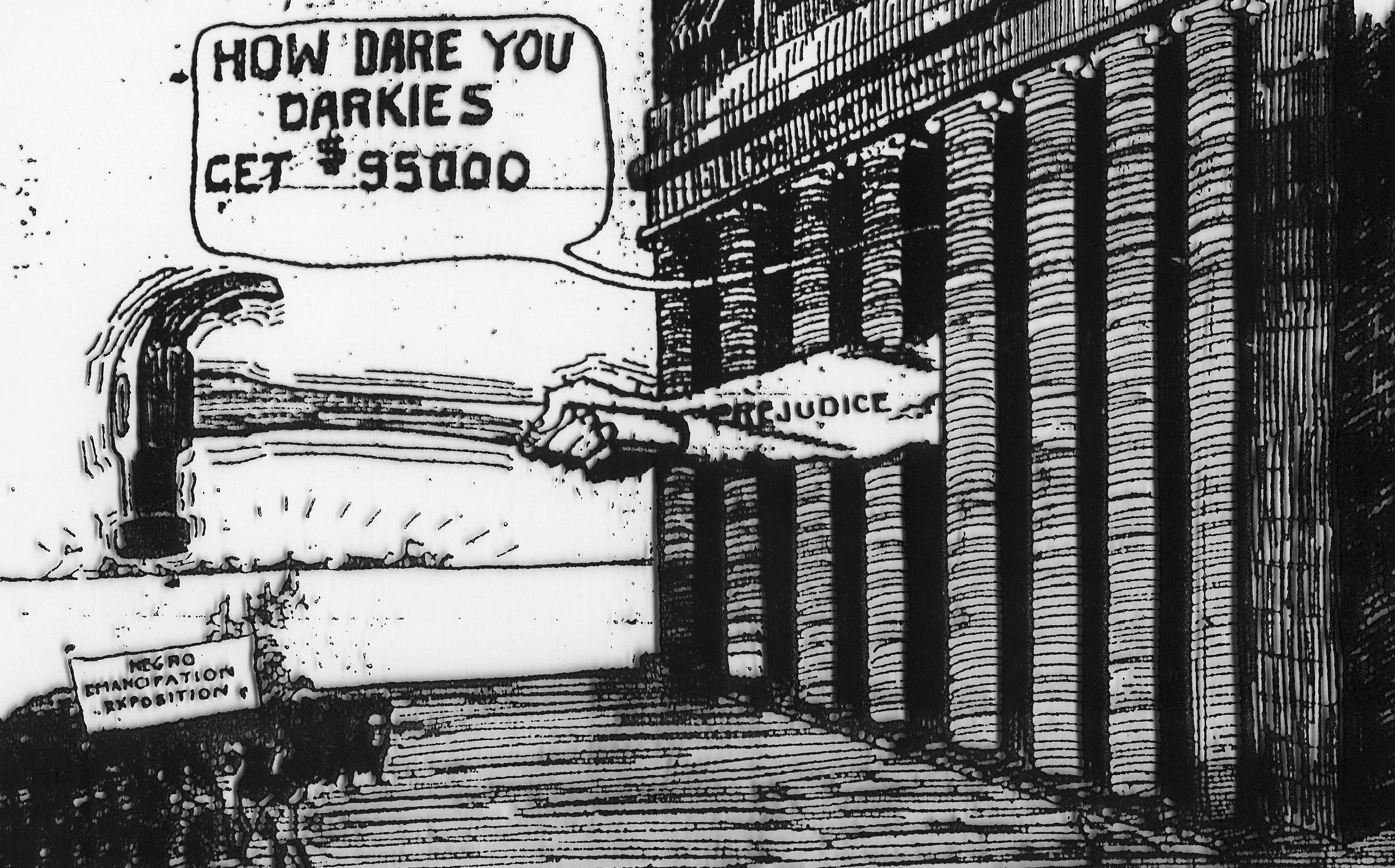

The exposition sparked racial conflict as white-owned Philadelphia newspapers, especially the North American, portrayed the event as a corrupt scheme to funnel public money into the pockets of the ruling Republican Party political machine. The state funding was obtained by the first African American state legislator to be elected in Pennsylvania, West Chester-born Harry W. Bass (1866-1917), a Republican, and exposition organizers rented an office from the Republican Party at 1352 Lombard Street, which the North American labeled “the notorious Senate Club.” Development in the area of Broad Street and Oregon Avenue would potentially benefit property owned in South Philadelphia by political boss William Vare (1867-1934). Such accusations were vigorously challenged by the African American-owned Philadelphia Tribune. Claims of corruption were never substantiated, but the exposition ran over budget by $4,000 and a sculptor and exposition workers protested afterward that they had not been paid.

After 1913, the site of the Emancipation Exposition was landscaped according to plans by the Olmsted Brothers of Brookline, Massachusetts, and in 1926 the resulting park became the location for the eighty-foot-tall, electrified Liberty Bell that served as gateway to the Sesquicentennial International Exposition. With South Philadelphia dominated by Italian immigrants and their descendants, the square in 1937 was renamed Marconi Plaza to honor Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937), the recently deceased Italian inventor of wireless telegraphy. Later additions to the plaza, including the Christopher Columbus monument originally located in Fairmount Park, added to the site’s recognition as a place for Italian-American community and commemoration. The Pennsylvania Emancipation Exposition of 1913, significant in its time for African American residents of Philadelphia, left little trace on the landscape or in published histories of Philadelphia.

Charlene Mires is the author of Independence Hall in American Memory (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002) and Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden.

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University.