Pennsylvania Prison Society

By Laura Michel

Essay

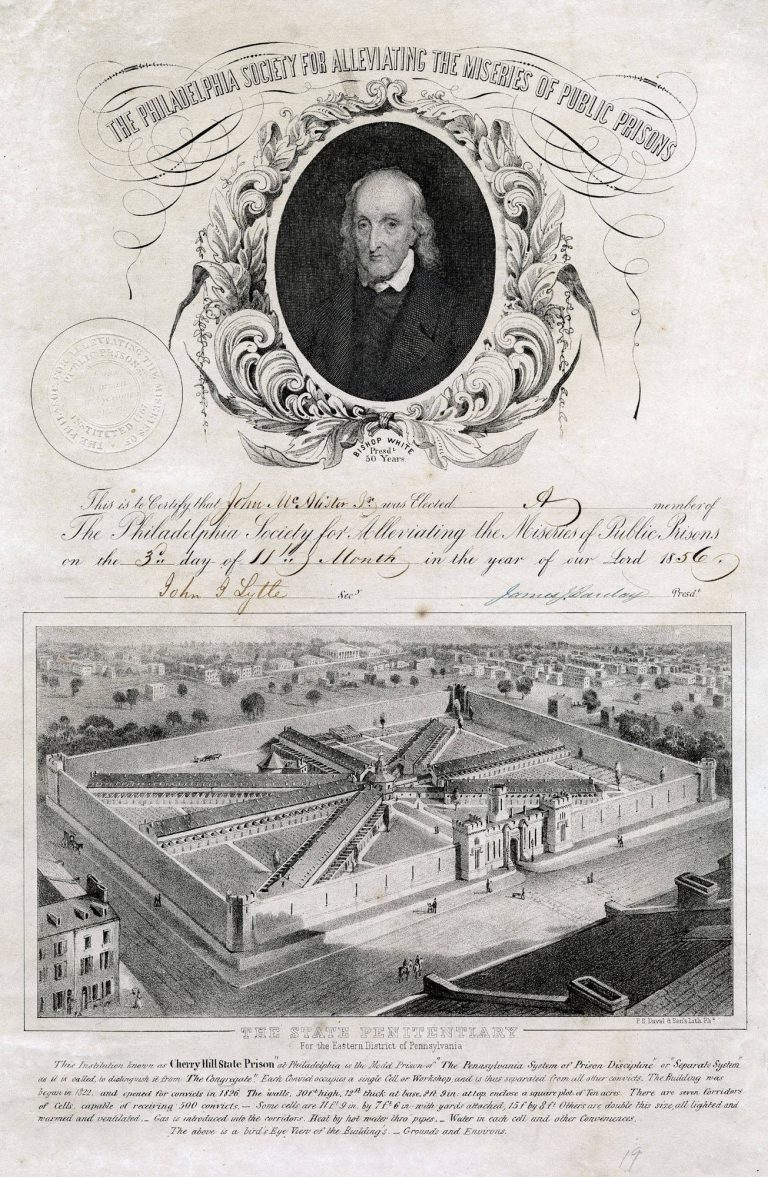

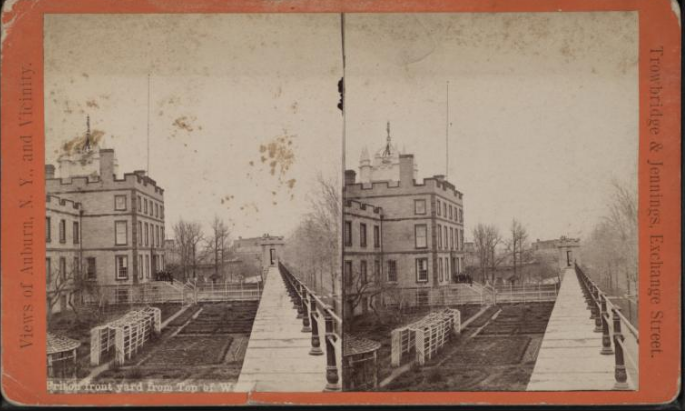

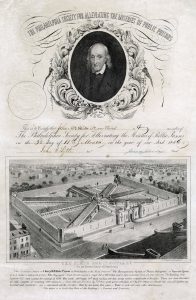

Founded in 1787 as the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons, the Pennsylvania Prison Society quickly became a leading advocate for the humane and salutary treatment of the incarcerated. From the restructuring of the Walnut Street Jail in the eighteenth century, to the construction and oversight of the Eastern State Penitentiary in the nineteenth, and its ongoing work as a social casework agency, the society’s efforts shaped correctional practices in Pennsylvania and beyond.

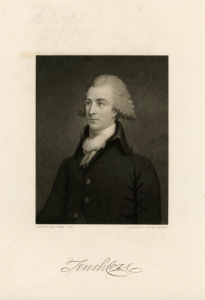

Although it soon gained international renown, the Pennsylvania Prison Society began humbly. As was typical in eighteenth-century Philadelphia, many of the group’s founders, including Caleb Lownes (1754–1828), Christopher Marshall (1709–97), Isaac Parrish (1734–1826), and Thomas Wistar (1765–1851), were prominent members of the Religious Society of Friends (the Quakers). From the outset, however, the Prison Society was decidedly nondenominational. William White (1748–1836), a bishop in the Episcopal Church, served as the organization’s first president, a position he held for forty-nine years until his death in 1836. Many of the society’s charter members were men of both local and national (and even international) repute. Physician and Declaration of Independence signer Benjamin Rush (1746–1813), politician Tench Coxe (1755–1824), and publisher Zachariah Poulson (1761–1844) all attended the society’s first meeting on May 8, 1787.

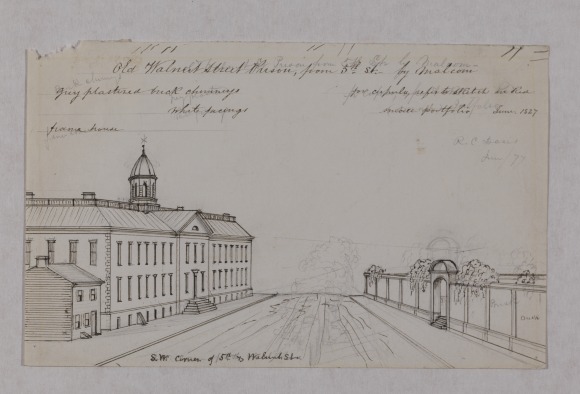

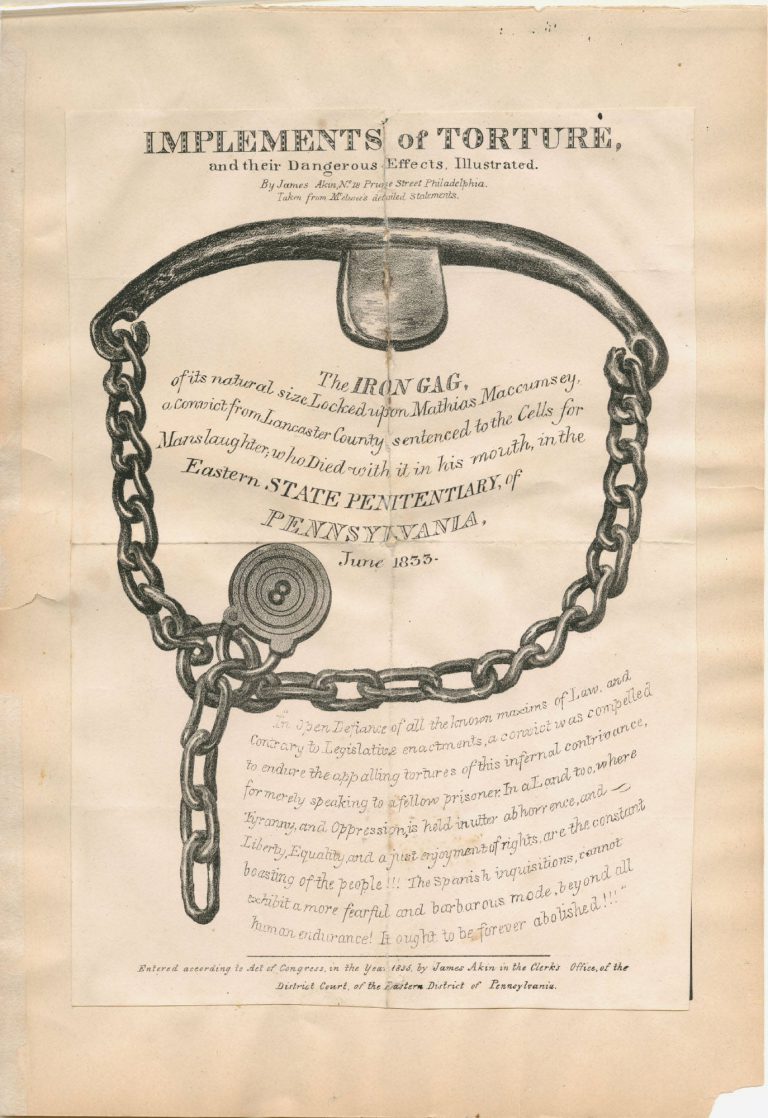

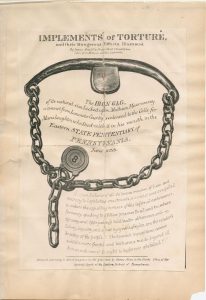

Spurred by reports of deplorable conditions in Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail, the society appointed an acting committee of six to ascertain the conditions of confinement and its effect on inmates’ moral and physical wellbeing. Prison Society visitors found a chaotic institution where inmates of all types, ages, and sexes mixed indiscriminately in an environment rife with obscenity, idleness, and vice. Realizing that the direct relief offered to prisoners in the form of bibles, clothing, medical care, and cash would not address these broader problems, the society also turned its efforts toward legislative change. Proposed reforms included abolishing the use of iron shackles and establishing a set salary for the jailer to avoid corruption.

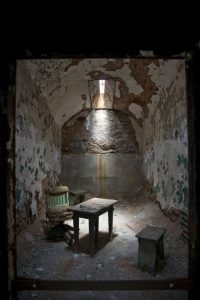

Most significantly, the Prison Society supported the solitary confinement of all prisoners. Influenced by the writings of the British prison reformer John Howard (1726–90), the proposed “separate system” would prevent hardened criminals from corrupting first-time offenders and would provide all inmates with the space needed for serious reflection and reform. Following legislative approval in 1790 for the separation of prisoners by age, gender, and crime committed, the Walnut Street Jail and the Pennsylvania Prison Society became models for prison reform efforts throughout the United States and in Europe.

Even as the Walnut Street Jail earned accolades from visitors, the Pennsylvania Prison Society was far from satisfied on the state of correctional practices. After a deadly riot at Walnut Street in 1820, Prison Society members escalated calls for a larger state institution purpose-built for the separation of all prisoners. In 1829, the first group of prisoners moved into individual cells at the new Eastern State Penitentiary. Though technically a state-run institution, the Prison Society served as sole outside overseer of the facility and active society members Roberts Vaux (1786–1836), Thomas Bradford (1781–1857), and John Bacon (1779-1859) filled three of the eleven state-appointed commissioner positions, while Samuel R. Wood (1776-?) served as the first warden of Eastern State.

Much of the society’s activity in the nineteenth century centered on the oversight of Eastern State and defense of the separate system, which became known as the “Pennsylvania System.” In 1845, largely in response to growing criticism from opponents of such extreme solitary confinement, the society established Journal of Prison Discipline and Philanthropy (later renamed The Prison Journal) to improve public outreach. Early editions extolled the successes of the Pennsylvania System alongside reports of the achievements and deficiencies of penal practices elsewhere in the United States and abroad.

Although the Pennsylvania System spread to Europe, Asia, and Latin America, the practice quickly fell out of favor in the United States. In part due to ongoing questions about the morality of solitary confinement, the scheme was ultimately abandoned because of the untenable costs of providing separate living, working, eating, and exercise quarters for every inmate. In response to these changes, the Pennsylvania Prison Society shifted its attention in the early twentieth century to other pressing issues, including parole and probation standards and the use of prison labor. Over the course of the twentieth century, the society’s activities were increasingly professionalized, with paid staff working with prisoners and their families to ensure legal and just treatment within the correctional system. Nevertheless, the Prison Society’s commitment to the humane and just treatment of prisoners remained at the core of its mission as the group continued to serve as an important advocate for the incarcerated and a leading voice in penal reform.

Laura Michel is a Ph.D. student in History at Rutgers University–New Brunswick. She studies issues surrounding crime, poverty, and philanthropy in the early modern Atlantic World.

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Questions of ethics haunt Eastern State Penitentiary (WHYY, July 26, 2011)

- $3.5 million grant to help Philly cut inmate population, launch other prison reforms (WHYY, April 13, 2016)

- Eastern State Penitentiary focus shifts from Al Capone to prison policy (WHYY, May 6, 2016)

- For the first time, historic prison offers tours of the hospital (WHYY, May 1, 2017)

Links

- Pennsylvania Prison Society

- The Prison Journal

- Walnut Street Prison (JRank Legal Encyclopedia)

- Friends (Quakers) In Prison Reform (Social Welfare History Project, Virginia Commonwealth University)

- Eastern State Penitentiary Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Eastern State Penitentiary (PhillyHistory Blog)