Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) Strike

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

The Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) strike, a five-day stoppage of the city’s mass transit system during World War II, resulted from longstanding racial animosities. Preceded by years of protest and ending only after the dispatching of federal troops, the strike exposed the dangers of workplace discrimination while threatening the material output of the nation’s third-largest war production center.

During World War II, thousands of African Americans came to Philadelphia seeking employment. The PTC, a semipublic agency operating the city’s trolleys, buses, and subways, prevented the hiring (or promotion) of black workers to motormen or conductors and consigned them to jobs as porters, messengers, or tracklayers. With many black Americans fighting overseas, those at home felt such discrimination violated American values. Philadelphia NAACP Executive Secretary Carolyn Davenport Moore (1916-98) organized a concerted response. By coordinating efforts with black churches, ward leaders, and union representatives, Moore raised awareness of the issue, leading to an October 1943 march on City Hall calling for an end to the PTC’s discriminatory practices. The following month Malcolm Ross (1895-1965), chairman of the federal Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC), demanded that beginning on August 1, 1944, the PTC promote black employees. White members of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Employees Union (PRTEU) threatened to create chaos in the city if black drivers were permitted.

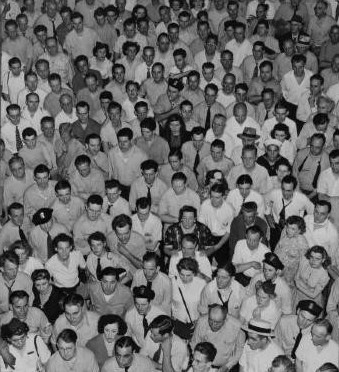

While PTC management agreed in principle with Ross’s order, he argued that black workers could only be promoted with consent from the PRTEU. The impasse prompted the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), with which the PRTEU was not affiliated, to initiate bargaining talks in March 1944. Promoting “multiracial unionism” during the war, the CIO by July persuaded PTC management to agree to integration. On August 1, determined to protect their jobs (and those of returning white soldiers), the PRTEU shut down the entire Philadelphia mass transit system. In retaliation, a number of black citizens attacked white-owned businesses, broke windows, and slashed police car tires. With many of the city’s defense workers (black and white) relying on trolleys and buses to reach their jobs, Philadelphia’s wartime production capacity suffered.

With the CIO and War Labor Board condemning the strike, on August 5 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945) dispatched federal troops to the city. Under the command of Major-General Philip Hayes (1887-1949), 4,000 soldiers, all prepared to drive trolleys and buses, arrived to restore order. Hayes ordered strikers to return to work the following day; penalties for disobeying included canceled draft deferments or permanent ineligibility for defense work. On August 6, 1944, the strike ended. For ten days afterward, army troops rode in all vehicles to maintain the peace.

By October, the PTC counted sixteen black drivers and within one year, the company’s 900 black employees held positions ranging from drivers and conductors to spots on the publicity staff. Yet aging infrastructure, declining ridership, and a series of additional strikes between 1946 and 1967 strained the company’s fortunes. In 1968, the newly created Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA), a nonprofit agency, purchased the PTC for $48 million and assumed control of its transit lines.

Stephen Nepa received his M.A. from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and his Ph.D. from Temple University. He teaches history at Temple University, Rowan University, and Moore College of Art and Design and appears in the Emmy Award-winning series Philadelphia: the Great Experiment.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History