Pine Barrens

Essay

New Jersey’s Pine Barrens, the forest and wetlands area also known as the Pinelands or the Pines, have played a varied but vital role in the region’s cultural and economic history. The Pine Barrens have, over time, been a home to Native American populations, a center of early American industry, a hub of military activity, and a focus of ecological and recreational interest. Although inhospitable to most forms of intensive agriculture, the Pinelands have been a crucial site for the commercial farming of blueberries and cranberries, two of New Jersey’s most valuable fruit crops.

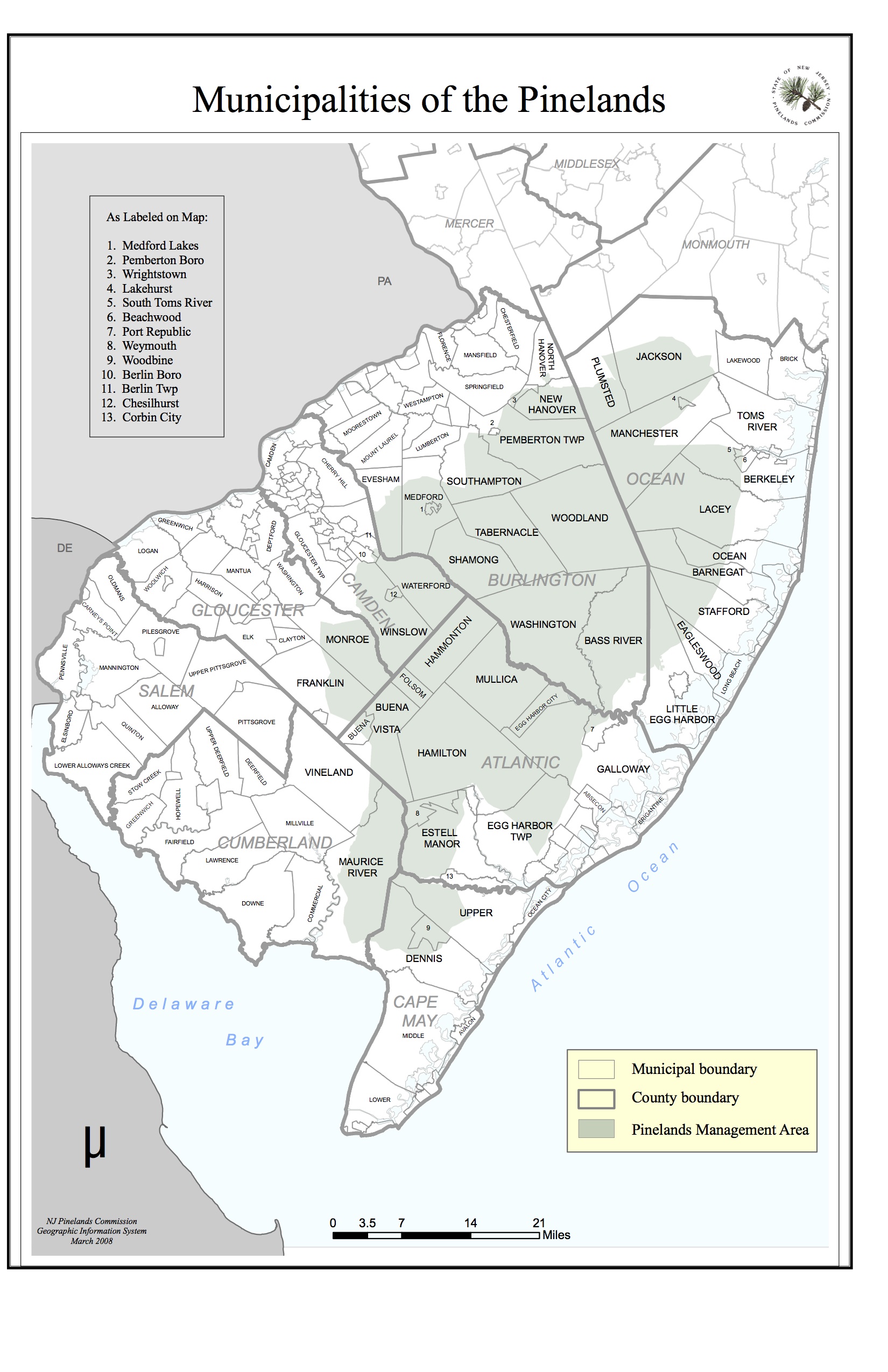

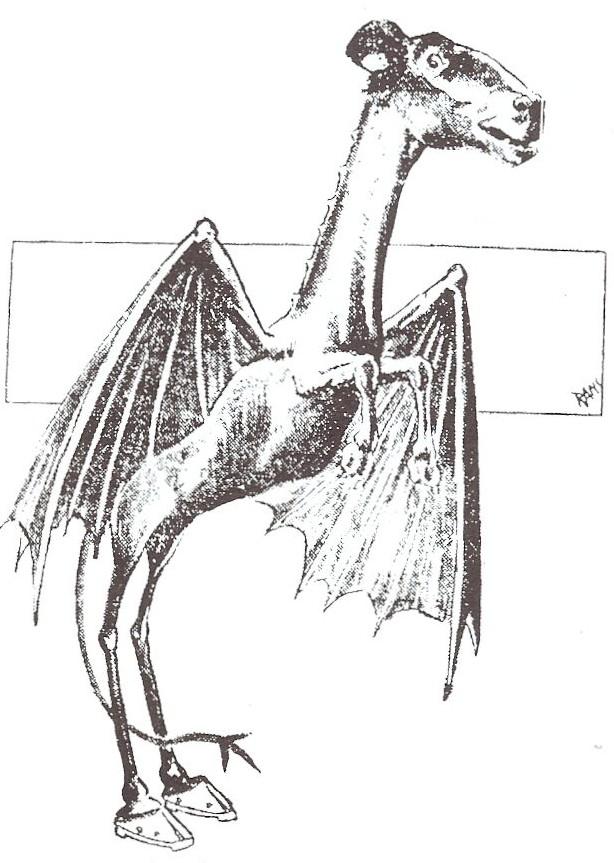

The Pine Barrens are characterized by high water tables and acidic, nutrient-poor, sandy soil, which supports a broad range of plant and animal life, including rare insectivorous plants, dwarf pine species, and the Pine Barrens tree frog. Much of this habitat is contained within the New Jersey Pinelands National Reserve, a 1,100,000-acre area that spans seven counties and occupies about 22 percent of the state’s land mass. Notable residents of this region have included Deborah Leeds (1685-1748), who, according to folklore, gave birth to the Jersey Devil, a legendary winged monster with cloven hooves and a forked tail. The area was also home to James Still (1812-82), the self-taught “Black Doctor of the Pines.”

Archaeological evidence indicates that humans began inhabiting the region around 10,000 B.C.E. While the land proved unable to support intensive agriculture, these early residents created small settlements sustained through hunting and fishing. The best-known native inhabitants were the Lenape, who used controlled fires to remove underbrush that discouraged hunting and agriculture. Because of the environs’ poor soil, the region did not attract significant European settlement until the late seventeenth century, when colonists began establishing whaling and shipbuilding settlements on coastal perimeters of the woodlands. These industries made the Pine Barrens a valuable source of lumber and other materials needed to manufacture pitch, tar, and turpentine, leading to the growth of sawmills and early Pinelands towns such as Browns Mills, Dennisville, Tuckahoe, and Port Elizabeth. The area’s unique plant life also attracted early botanists.

Rise of Bog Iron

As colonial settlement intensified, the Pine Barrens also proved to be a valuable source of bog iron deposits, wood for charcoal, peat, and sand for glass production. Beginning in the early eighteenth century, sawmills and gristmills were established in the Pines. The Lenape also continued to reside in the Pinelands until treaties negotiated in the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War enacted significant resettlement efforts. In 1758, Brotherton, the first Indian reservation in the colonies, was established in present-day Indian Mills. By 1800, the majority of the Lenape had been forced to migrate out of the region. The Pineland’s nonnative population also began to significantly increase around this time, in large part due to the establishment of iron furnaces and glass factories.

The iron industry thrived in the Pine Barrens throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Beginning in 1755, Charles Read (1715-74), a former Philadelphia merchant who had moved to Burlington, New Jersey, to pursue a political career, purchased property in the Pinelands in the hopes of establishing a chain of ironworks and forges in Batsto, Taunton, Etna, and Atsion. After its construction in 1766, Batsto Iron Works became one of the region’s first and most prominent sites of iron production, though financial troubles soon forced Read to gradually split up and sell these properties to investors from Philadelphia and the surrounding New Jersey region. These investors and other early iron-making industrialists oversaw iron production at more than thirty forges and furnaces throughout the Pines, such as the Atsion Iron Works, Cohansie Iron Works, Etna Furnace, Martha Furnace, and Speedwell Furnace. These sites played a pivotal role in supplying military forces during the American Revolution and the War of 1812.

Forges and furnaces were joined by other industries, such as the great glass-making factory of the Pennsylvania landowner and glassmaker Caspar Wistar (1696-1752), who began operating the Wistarburgh Glass Manufactory in violation of colonial laws in 1739 near Alloway, New Jersey. In 1779, the Wistarburgh Glass Manufactory was joined by the Stanger Glass Works, founded by Solomon Stanger (1743-94), a former employee of Wistar, in what later became Glassboro. By the nineteenth century, more than twenty glass manufactories had been established in Pinelands manufacturing towns like Atco, Barnegat, Clementon, Egg Harbor, Estellville, and Green Bank.The region also developed cotton mills after 1810 and paper mills after 1832. Between 1830 and 1840, residents began cultivating cranberries, a water-intensive crop well-suited to the wetlands of the Pines.

Agricultural Limits

Iron production in the Pine Barrens declined precipitously in the mid-nineteenth century as a result of competition from nearby producers in Pennsylvania, collapsing entirely by 1869. Efforts in 1876 by the wealthy Philadelphia industrialist Joseph Wharton (1826-1909) to establish agricultural production of sugar, sugar beets, and cotton also ended in failure, as did his 1891 attempt to export water from his Pine Barrens property to Philadelphia (the New Jersey legislature quickly prohibited the practice). As the region’s industries declined and many of the former hubs of industry were abandoned, the forests instead became a pathway to more enticing locations. Early railroads crossed through the Pine Barrens as they radiated from the transportation hubs of Philadelphia and New York to South Jersey’s early suburbs and the emerging resorts such as Atlantic City and Cape May.

By the early twentieth century, the inhabitants who remained in the Pine Barrens lived in a rural economy based at least partially on hunting and gathering, even as surrounding localities became increasingly densely settled and industrialized. As a result of this cultural and demographic divide, populations surrounding the Pinelands began using the derogatory term “Pineys” to refer to the region’s residents. In 1912, this reputation led the eugenicist Henry H. Goddard (1866-1957) to publish The Kallikak Family, which presented the pseudonymous Pinelands family as a case study in genetic inferiority.

The Pinelands were soon put to new economic uses, however. In 1916, Pine Barrens resident Elizabeth White (1871-1954), who had been raised in a cranberry-farming family, successfully collaborated with botanist Dr. Frank Coville (1867-1937) to develop a hybrid blueberry plant for commercial cultivation. This scientific breakthrough led to commercial blueberry farms on White’s property at Whitesbog and elsewhere. Along with cranberries, blueberries became a staple commercial crop of the region. In 1917, following the outbreak of World War I, the Pinelands area also became the site of the military installations of Fort Dix and Lakehurst Naval Air Station. A third military base, the Millville Army Air Field, was established in 1943, during World War II.

Despite these developments, the Pine Barrens continued to be largely rural and sparsely populated in comparison to neighboring regions. This made it a point of interest for scientists and environmentalists seeking to study or call attention to its unique ecosystem and its endangered plant and animal life. In 1954, the state of New Jersey purchased Joseph Wharton’s old 156-square-mile estate, which had lain vacant since Wharton’s death in 1909. The purchase, which gave the claim to the vast water resources of the tract, also more than doubled the acreage of state parkland. In 1978, Congress designated the federal Pinelands National Reserve (the first such reserve to be created under the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978), and state and federal agencies were established to control development in the reserve area. The ecosystem was also declared to be a U.S. Biosphere Reserve in 1983 and an International Biosphere Reserve in 1988 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Featuring local, state, and federal public parks, wildlife management areas, and the historic industrial villages of Batsto and Double Trouble, the Pinelands continue to be a significant tourism and recreational resource for the region.

Skylar Harris is Grants Program Manager, New Jersey Historical Commission, and an adjunct faculty member of the Rowan University History Department and American Studies Department. Her publications include “Mind over Matter: Social Justice, the Body, and Environmental History,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 79, no. 4 (2012): 440-450, and she has contributed to reference works Water Politics and the Environment in the United States, American Countercultures: An Encyclopedia of Political, Social, Religious, and Artistic Movements, Dictionary of American History: Third Edition Dynamic Reference Edition, The Encyclopedia of American Environmental History, The Encyclopedia of the History of Invention and Technology, The Encyclopedia of the Industrial Revolution in World History, The Encyclopedia of the Modern World: 1750 to the Present, and The U.S. Government and the Environment: A Reference Encyclopedia.

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Four former NJ governors oppose Christie plan for change on Pinelands Commission (WHYY, March 4, 2015)

- Protection zone for NJ's Pine Barrens to expand (WHYY, July 9, 2015)

- Pipeline application approval by Pinelands Commission chief raises eyebrows (WHYY, August 20, 2015)

- Pinelands wildfire is fully contained (WHYY, September 9, 2015)

- South Jersey Gas pipeline plan still fueling dispute, despite Pinelands Commission OK (WHYY, October 19, 2015)

- Proposed 'Pinelands' pipeline faces crucial vote on Friday (WHYY, February 22, 2017)

- N.J. launches pilot program to protect Pine Barren's intermittent ponds from off-road vehicles (WHYY, March 20, 2017)