Point Breeze (Bonaparte Estate)

By Richard Veit

Essay

Joseph Bonaparte’s Point Breeze estate was one of the finest country houses in the Delaware Valley. Similar grand houses once graced the Delaware Valley, especially upriver from Philadelphia and along the Schuylkill. The first was likely Pennsbury Manor, the American home of William Penn (1644-1718). Many of these country houses still stand, including the Woodlands, Andalusia, Lemon Hill, and others. Country estates provided the elite with refuge from the heat and disease of the city during the summer months and provided wealthy Philadelphians with showplaces for their gardens and architecture.

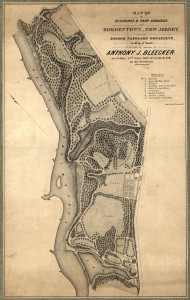

Although only traces of the original Point Breeze estate in Bordentown, New Jersey, remain, extensive archaeological deposits survive to reveal the grandeur of the home occupied by Joseph Bonaparte during his American sojourn (1815-39). Famous for its picturesque landscape, wonderful gardens, extensive art collection, and large library, it was a center of social life in the Delaware Valley. Here Joseph entertained French emigres and Philadelphia elites, played host to visiting diplomats, artists, and naturalists, and stayed abreast of the latest political news from Europe. Indeed, everyone from American politicians to the Marquis de Lafayette and Mexican revolutionaries visited Joseph and solicited his counsel.

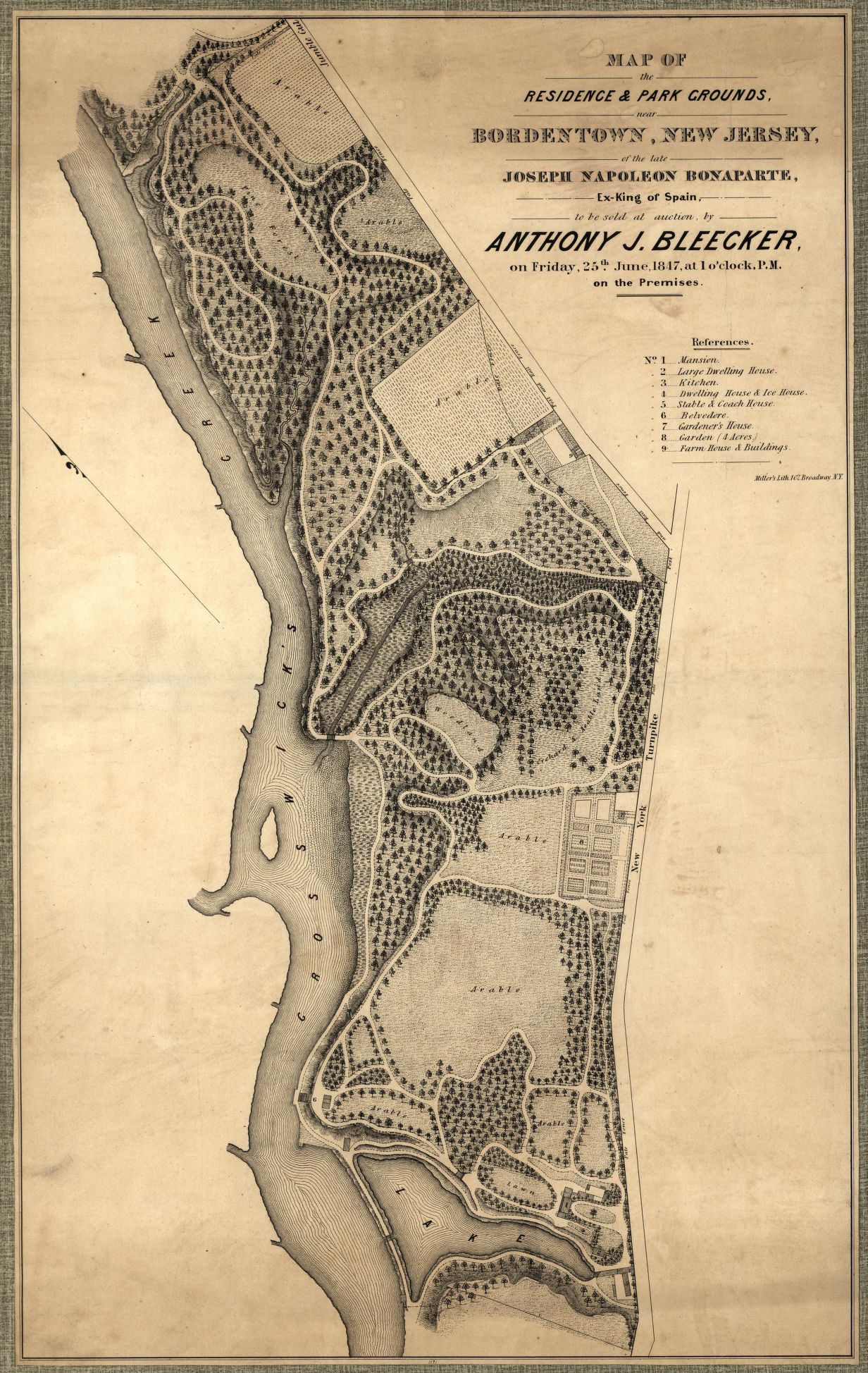

Joseph Bonaparte (1768-1844), the elder brother of Napoleon, immigrated to the United States at the close of the Napoleonic Wars and settled in the Delaware Valley. Known as the Comte de Survilliers, Joseph was a patron of the arts and sciences and owned a townhouse in Philadelphia. However, he was best known for his lavish country estate at Point Breeze in Bordentown. Joseph, who had owned fine estates in Europe, chose to live in Bordentown because of its location on the main route between Philadelphia and New York and because of the property’s exceptional setting. At Point Breeze he constructed a pair of palatial houses. The first was destroyed by a fire in 1820, the second stood into the mid-nineteenth century. He also laid out one of the finest picturesque gardens in North America.

Bonaparte’s Park

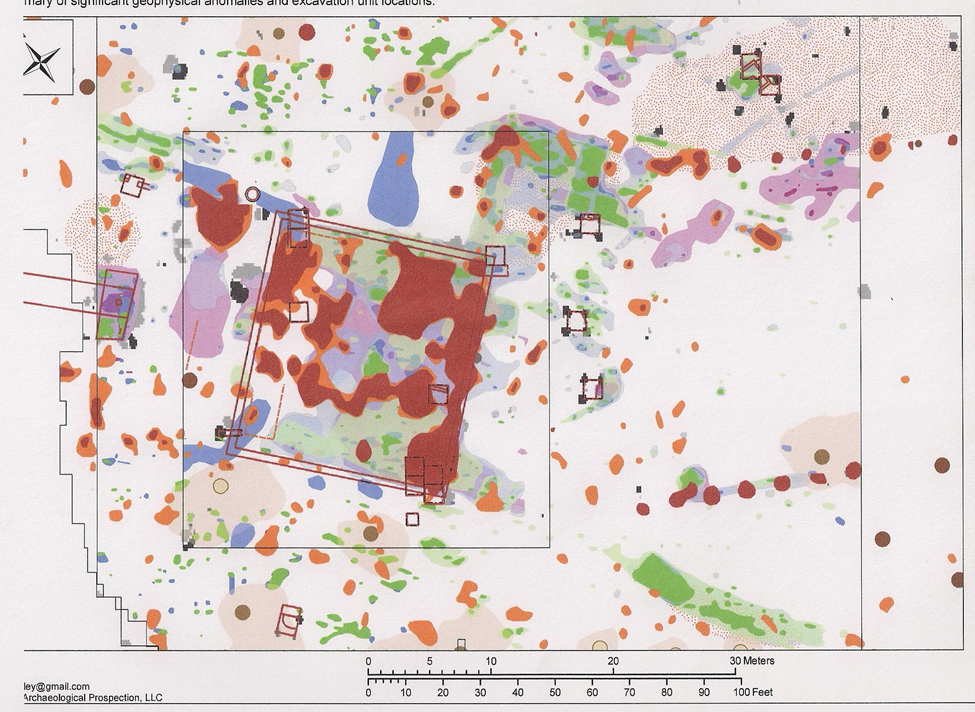

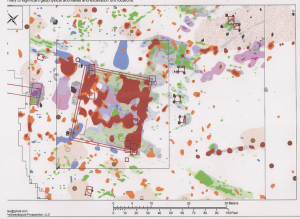

Joseph’s country estate, sometimes called Bonaparte’s Park, attracted many luminaries who commented on it widely. It was one of the sights to see in the Delaware Valley. After Joseph’s return to Europe, the property remained a private estate/park owned by the Richards, Beckett, and Hammond families. In 1941 Divine Word Missionaries, a Roman Catholic religious community, acquired the property. Divine Word employed the property first as a seminary and subsequently as a retirement community. In 2007, archaeology, both below and above ground, provided a wealth of new information about the layout of the site and especially Joseph’s use of the landscape as a stage for enacting his role as a king in exile.

Born on the Mediterranean island of Corsica, Joseph Bonaparte trained as a lawyer and served as a member of the Council of 500, the lower house of the French legislature during the French Revolution. A distinguished diplomat, he helped negotiate the Louisiana Purchase (1803). After his brother became emperor, Joseph was made King of Naples and Sicily (1806-08). In this role, he was seen as a democratically inclined monarch. Later, Napoleon made him King of Spain (1808-13). This proved considerably more challenging, and during the Peninsular Wars he was driven out of Spain. A close confidante of his brother, he supported his brother’s return from exile in Elba in 1815, and following his brother’s defeat at Waterloo, encouraged him to flee to America. Napoleon chose not to, but Joseph escaped to the United States to begin a new life.

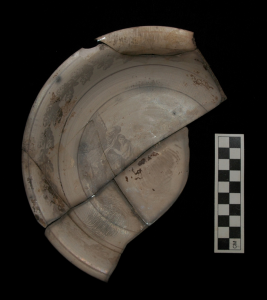

Joseph wanted to live between Philadelphia and New York, where he could rapidly receive the latest news from Europe. In 1816, he purchased Point Breeze, the country home of Stephen Sayre (1736-1818), an American diplomat and adventurer. Point Breeze soon became renowned as one of the finest houses in the United States. The home consisted of a main block, three stories tall, with flanking wings, and a tower providing a view of the surrounding countryside, the Belvedere. It resembled Joseph’s European estates Prangins and Mortefontaine and was built with funds secretly removed from France by his trusted secretary Louis Mailliard (1795-1872). It contained an extensive collection of art, including statues by Canova and paintings by David including Napoleon Crossing the Alps. In 1820 a fire of unknown cause destroyed the house. Joseph was not home at the time. However, the residents of Bordentown and his servants were able to save many of his possessions, including much of his art collection.

New House Built on Site

Joseph quickly rebuilt, employing his former stables as the core of his new home. This second house was also known for its galleries and was connected by a series of tunnels to outbuildings and a home, the Lake House, occupied by his daughter Zenaïde and her husband Charles-Lucien-Bonaparte, a noted naturalist.

At Point Breeze Joseph also created a private park. He laid out several miles of roads, bridged streams, created an artificial lake, built docks and landings, and installed an array of statuary. His property soon became well known as a center of social life in the Delaware Valley. It was also the heart of a considerable French expatriate community. Joseph opened his property to the public and was often seen working on the grounds. His home was the subject of numerous artists. They emphasize the scenic nature of the property with winding roads, beautiful plantings, and pleasing vistas.

In 1832, Joseph returned to Europe, living in London until 1838, then returning to Point Breeze. In 1839 he left Point Breeze and again returned to Europe where he reunited with his wife, Julie Clary. He suffered a major stroke in 1840 and passed away in Florence four years later. The property passed to his grandson, who quickly auctioned off the household contents, including the library and artwork. In 1850 the property was acquired by Henry Beckett, a British diplomat, who tore down the second Bonaparte house, likely because of the great expense needed to maintain it. After a succession of owners, the core of Point Breeze became the property of Divine Word Missionaries.

In 2007, at the request of Divine Word Missionaries and in an attempt to better document the history of this exceptional property, Monmouth University began an archaeological study of the property. Fieldwork was directed by Monmouth University archaeologists Richard Veit and Michael Gall, assisted by Gerard Scharfenberger and William Schindler. Even a century and a half after Joseph’s return to Europe, traces of his estate remained, including one original building, the Gardener’s Cottage, and ruins from the Lake House and the lodge. Some plantings likely dated from his occupation, as well as traces of his manmade lake, docks, and landings. Moreover, archaeological deposits associated with the earlier colonial and prehistoric occupations of the site were still present.

At Point Breeze, historical archaeology has proven to be a powerful tool for understanding one of the Delaware Valley’s finest country estates. It has also served to focus public and scholarly interest on an otherwise overlooked historic site. The destruction of Joseph’s first house by fire resulted in the creation of an extraordinary archaeological deposit that provided an unparalleled material record of the lifestyles of early American elites. Careful mapping of the remaining features of the estate illuminates how Joseph transformed his property into a new private park where he could play the role of king in exile. Even today, Point Breeze is an evocative reminder of a time when Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley were central to American intellectual and cultural life.

Richard Veit, Ph.D., is Professor of Anthropology and Chair of the Department of History and Anthropology at Monmouth University. He teaches courses on archaeology, New Jersey history, Native Americans, and historic preservation. He has authored or co-authored numerous articles and reviews and five books including Digging New Jersey’s Past: Historical Archaeology in the Garden State (Rutgers Press, 2002), New Jersey Cemeteries and Tombstones History in the Landscape (co-authored by Mark Nonestied, Rutgers Press, 2008), and New Jersey: A History of the Garden State (co-authored with Maxine Lurie, Rutgers Press, 2012). He also regularly presents on topics relating to historical archaeology and New Jersey history and has been a TED speaker.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University