Private (Independent) Schools

Essay

The private or independent schools in the Greater Philadelphia area came about mainly to satisfy a need felt by wealthy, white families to educate their children in a cultural and intellectual environment that would prepare them for the responsibilities befitting their gender, race, and class status. Most have existed for at least a century. Although never a large proportion of the region’s educational marketplace, they achieved respect based upon their associations with wealth and power, their academic excellence, and in many cases their religious affiliations. Nevertheless, they struggled with three important issues: access, location, and cost. Finding the right balance among them was a perpetual problem. Since the 1960s, they have addressed this problem by diversifying in many ways—in student body, curricula, and leadership. Ironically, this made them, as a group, more alike than different. But as a result, they lost an important part of their heritage—namely, the desire to preserve strict economic, social, and cultural distinctions.

Most of the region’s private and independent schools are concentrated in southeastern Pennsylvania and northern Delaware. South Jersey lagged behind because it did not have a critical mass of middle- and high-income residents at the beginning of the twentieth century when circumstances for founding such schools were most propitious. Protestant denominations and Catholic religious orders, both male and female, started many of them. They wanted a “protected education” that would reinforce their teachings. Sequestering students from those of different faiths and from the opposite sex screened out “undesirable” influences and temptations.

In 1689, members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) founded the first school in the region because they associated education with the common good as well as personal salvation. The William Penn Charter School was named for the document establishing it by Pennsylvania proprietor William Penn. In the beginning it taught rich and poor, Quaker and non-Quaker alike. By the twenty-first century, it could claim the honor of being the oldest Friends school in the world, the oldest elementary school in Pennsylvania, and the fifth-oldest elementary school in the United States. After occupying several sites in the old city, it moved in 1925 to the suburbanlike neighborhood of East Falls/Germantown. Its new address and high tuition made it inaccessible to many children. Friends Select School was originally “under the care” of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, a sponsorship later shared with the Central Philadelphia Monthly Meeting. The word “select” in its name indicated that only Quaker children were admitted (or selected); financial considerations brought this practice to an end in 1877.

Established in 1697 in what became Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, the Abington Friends School was under the care of the Abington Monthly Meeting. When it opened, it was in a completely rural area. The same could be said for the Westtown School, which was established on a farm in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in 1799. The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, which planned the school and brought it to fruition, purposely located it a day’s ride by stagecoach from Philadelphia to protect its students from the city’s corrupting influence. Not surprisingly, it was a boarding school though it eventually accepted day students as its surroundings became more populated.

Established in 1697 in what became Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, the Abington Friends School was under the care of the Abington Monthly Meeting. When it opened, it was in a completely rural area. The same could be said for the Westtown School, which was established on a farm in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in 1799. The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, which planned the school and brought it to fruition, purposely located it a day’s ride by stagecoach from Philadelphia to protect its students from the city’s corrupting influence. Not surprisingly, it was a boarding school though it eventually accepted day students as its surroundings became more populated.

Most Quakers were clear about the different roles of men and women, but they vacillated for years on the subject of coeducation for children. Friends Select operated separate schools for boys and girls before consolidating them in the 1880s. Abington and Westtown Friends admitted both boys and girls in the beginning, but Abington excluded boys for three decades, a practice that ended only in the 1960s. Westtown kept the sexes apart until the late nineteenth century, when it gradually began to allow boys and girls to attend some classes together and play with one another under strict supervision. By contrast, it did not admit non-Quakers until the 1930s. The school incorporated for the first time in 2010, making it an independent Quaker prep school.

The George School, a Quaker school not affiliated with a Friends meeting, opened in 1893 and has been located in Newtown, Bucks County, ever since. It was named for John M. George, its principal donor, who along with other backers intended it to be a coeducational institution for Hicksite Quakers. Since the Westtown School was affiliated with the Orthodox movement, the George School saw itself as an alternative. Over the last fifty years, a large number of financially successful alumni have built one of the largest endowments of any private school in the greater Philadelphia region, facilitating the admission of low-income students. In 2006-2007 Westtown and George enrolled a much higher proportion of such students than all the other Quaker schools in the region (see chart in the image gallery at right). Nevertheless, both are schools for which family income remains a defining characteristic.

The George School, a Quaker school not affiliated with a Friends meeting, opened in 1893 and has been located in Newtown, Bucks County, ever since. It was named for John M. George, its principal donor, who along with other backers intended it to be a coeducational institution for Hicksite Quakers. Since the Westtown School was affiliated with the Orthodox movement, the George School saw itself as an alternative. Over the last fifty years, a large number of financially successful alumni have built one of the largest endowments of any private school in the greater Philadelphia region, facilitating the admission of low-income students. In 2006-2007 Westtown and George enrolled a much higher proportion of such students than all the other Quaker schools in the region (see chart in the image gallery at right). Nevertheless, both are schools for which family income remains a defining characteristic.

Suburbanization affected some Quaker schools more than others. Friends Select School remained in downtown Philadelphia, eventually settling in 1937 on the grand boulevard that became known as the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Founded in 1845 by the Germantown Monthly Meeting, Germantown Friends School never left its original location (Coulter Street near Germantown Avenue) even though this neighborhood, which was once almost entirely white and middle class, diversified demographically and deteriorated physically. The school has always been coeducational, but until the early twentieth century,

Suburbanization affected some Quaker schools more than others. Friends Select School remained in downtown Philadelphia, eventually settling in 1937 on the grand boulevard that became known as the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Founded in 1845 by the Germantown Monthly Meeting, Germantown Friends School never left its original location (Coulter Street near Germantown Avenue) even though this neighborhood, which was once almost entirely white and middle class, diversified demographically and deteriorated physically. The school has always been coeducational, but until the early twentieth century, it admitted only Quakers. Friends Central School, on the other hand, started life in 1845 at Fourth and Cherry Streets before moving to the fringe of the developed city (Fifteenth and Race Streets) just before the Civil War. It left Philadelphia altogether in 1925, relocating to Wynnewood, Montgomery County.

it admitted only Quakers. Friends Central School, on the other hand, started life in 1845 at Fourth and Cherry Streets before moving to the fringe of the developed city (Fifteenth and Race Streets) just before the Civil War. It left Philadelphia altogether in 1925, relocating to Wynnewood, Montgomery County.

Suburbanization caught up with both the George School and Abington Friends. As Bucks County’s population grew in twentieth century, the George School accepted an increasing number of day students. Situated in eastern Montgomery County, Abington Friends expanded its campus, allowing it to stay in the same place under the same management longer than any other school in the nation. All of these Quaker schools have relied on academic rigor and a high college acceptance rate to attract both urban and suburban applicants since at least the middle of the twentieth century.

Not to be outdone, Quakers in New Jersey founded two schools, Moorestown Friends in 1785 and Haddonfield Friends one year later. The latter accepted both Quakers and non-Quakers from the beginning. Like most Friends schools, it required students to attend meeting once per week. Founded by the Wilmington Monthly Meeting in 1748, Wilmington Friends, in Wilmington, Delaware, has been an independent day school for decades. Before public schools existed in Delaware, it served a wide array of students, but in recent decades it has concentrated on those aspiring to attend college. It moved to suburban Alapocas in 1937.

The percentage of Quakers enrolled at Friends schools has diminished over the years in part because, like most private schools in the region, they have increasingly sought to enroll many different kinds of students. At the same time, these schools have always stressed such core Quaker values as equality, simplicity, justice, integrity, and service to others. None of these values is exclusive to Quakers, of course, but sometimes they conflicted with practices associated with a rigorous college preparatory education. Germantown Friends, for example, eliminated academic awards for its students in 2002. As a rule, the Quaker schools have not required try-outs for their athletic teams; anyone who comes forward can participate.

Roman Catholic Schools

The Roman Catholic Church sponsored many private schools in the region. Even more than the Quakers, the Catholics were committed to religious schools for their children, and some—especially those for girls—practiced single-sex education. In time, they all admitted non-Catholics and some even opted for coeducation, both of which helped make ends meet. Waldron Mercy Academy, for example, brought together two single-sex private schools in Merion, Pennsylvania —Waldron Academy for Boys and Merion Mercy Academy for Girls—in a merger that took place in 1987. That there was some precedent for this combination may be inferred from the history of their mutual predecessor, Mater Misericordiae Academy (1885). It had a young boys department that joined Waldron Academy for Boys when it opened in 1923.

The Roman Catholic Church sponsored many private schools in the region. Even more than the Quakers, the Catholics were committed to religious schools for their children, and some—especially those for girls—practiced single-sex education. In time, they all admitted non-Catholics and some even opted for coeducation, both of which helped make ends meet. Waldron Mercy Academy, for example, brought together two single-sex private schools in Merion, Pennsylvania —Waldron Academy for Boys and Merion Mercy Academy for Girls—in a merger that took place in 1987. That there was some precedent for this combination may be inferred from the history of their mutual predecessor, Mater Misericordiae Academy (1885). It had a young boys department that joined Waldron Academy for Boys when it opened in 1923.

Three Catholic private schools began as feeders for Roman Catholic colleges. Such an arrangement was not unusual at a time when most small colleges had to prepare students for admission by sponsoring high schools or academies. The oldest is Malvern Preparatory School in Malvern, Chester County. Operated by the Order of St. Augustine, it began in 1842 on the campus of what was then Villanova College. In 1922, partly in an effort to make an even clearer distinction between the college and the academy, its secondary department moved to Malvern where it served a largely suburban population. Other early feeder schools included St. Joseph’s Preparatory and La Salle College High School. “St. Joe’s Prep” traces its roots to the founding of St. Joseph’s College (chartered in 1851), both under the a

Three Catholic private schools began as feeders for Roman Catholic colleges. Such an arrangement was not unusual at a time when most small colleges had to prepare students for admission by sponsoring high schools or academies. The oldest is Malvern Preparatory School in Malvern, Chester County. Operated by the Order of St. Augustine, it began in 1842 on the campus of what was then Villanova College. In 1922, partly in an effort to make an even clearer distinction between the college and the academy, its secondary department moved to Malvern where it served a largely suburban population. Other early feeder schools included St. Joseph’s Preparatory and La Salle College High School. “St. Joe’s Prep” traces its roots to the founding of St. Joseph’s College (chartered in 1851), both under the a uspices of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). The school and college were located initially at (Old) St

uspices of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). The school and college were located initially at (Old) St . Joseph’s Church on Willings Alley (between Third and Fourth Streets, and Walnut and Locust Streets). When the college moved to Seventeenth and Stiles Streets, the “Prep” went with it and remained there when the college relocated to City Avenue in 1927. After considering coeducation, the Prep decided to remain all male. La Salle College High School for boys came into being with the establishment of La Salle College in 1858. A century later it moved to a separate suburban campus in the affluent community of Wyndmoor, Montgomery County, while the college remained in the city.

. Joseph’s Church on Willings Alley (between Third and Fourth Streets, and Walnut and Locust Streets). When the college moved to Seventeenth and Stiles Streets, the “Prep” went with it and remained there when the college relocated to City Avenue in 1927. After considering coeducation, the Prep decided to remain all male. La Salle College High School for boys came into being with the establishment of La Salle College in 1858. A century later it moved to a separate suburban campus in the affluent community of Wyndmoor, Montgomery County, while the college remained in the city.

Like the Catholic prep schools in Pennsylvania, Archmere Academy in Claymont, Delaware, started as an all-boys school in 1932 but became coeducational in the early 1970s. The Norbertine Brothers founded it as a boarding school but eventually abandoned this policy due to space considerations.

Like the Catholic prep schools in Pennsylvania, Archmere Academy in Claymont, Delaware, started as an all-boys school in 1932 but became coeducational in the early 1970s. The Norbertine Brothers founded it as a boarding school but eventually abandoned this policy due to space considerations.

Catholic women’s religious orders established several girls’ schools in Philadelphia in the second half of the nineteenth century. Founded by the Sisters of Notre Dame in 1856, what became the Academy of Notre Dame de Namur educated both sexes at first. Moving west with the city, it opened a convent boarding and day school on fashionable Rittenhouse Square (Nineteenth Street below Walnut) in 1866. It remained there for nearly eighty years (1866-1944) before establishing a second campus in Villanova (Sproul Road) to which it moved its entire operation in 1967. By then, it was a day school for girls only, a policy that the move did

Catholic women’s religious orders established several girls’ schools in Philadelphia in the second half of the nineteenth century. Founded by the Sisters of Notre Dame in 1856, what became the Academy of Notre Dame de Namur educated both sexes at first. Moving west with the city, it opened a convent boarding and day school on fashionable Rittenhouse Square (Nineteenth Street below Walnut) in 1866. It remained there for nearly eighty years (1866-1944) before establishing a second campus in Villanova (Sproul Road) to which it moved its entire operation in 1967. By then, it was a day school for girls only, a policy that the move did  not change. The Sisters of St. Joseph established Mount St. Joseph Academy in 1858 on what later became the campus of Chestnut Hill College. It sought to instill a fear of God in girls about to enter polite society and impress upon them such values as modesty and chastity. It also sought to “recruit” young women for the sisterhood, and for many years some followed this path. But its primary objective soon became college preparation.

not change. The Sisters of St. Joseph established Mount St. Joseph Academy in 1858 on what later became the campus of Chestnut Hill College. It sought to instill a fear of God in girls about to enter polite society and impress upon them such values as modesty and chastity. It also sought to “recruit” young women for the sisterhood, and for many years some followed this path. But its primary objective soon became college preparation.

The Sisters of Mercy established what became Gwynedd Mercy Academy in 1863, and it moved several  times before settling in suburban Gwynedd Valley in 1947, where it shared a site with Gwynedd Mercy College. Nuns belonging to an order known as the Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary opened Villa Maria Academy in 1872. It occupied several sites before moving to the Chester County campus of Immaculata College in 1925. Along the same lines, the Ursuline Sisters established Ursuline Academy for girls in Wilmington, Delaware, in 1893. All these Catholic academies had mandatory religion classes, but they stopped requiring their students to attend Catholic religious services when many were no longer practicing Roman Catholics.

times before settling in suburban Gwynedd Valley in 1947, where it shared a site with Gwynedd Mercy College. Nuns belonging to an order known as the Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary opened Villa Maria Academy in 1872. It occupied several sites before moving to the Chester County campus of Immaculata College in 1925. Along the same lines, the Ursuline Sisters established Ursuline Academy for girls in Wilmington, Delaware, in 1893. All these Catholic academies had mandatory religion classes, but they stopped requiring their students to attend Catholic religious services when many were no longer practicing Roman Catholics.

Similar to the Roman Catholic academies, the Academy of the New Church grew up in a religious tradition. Established in Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania, in 1876, it was formed to train clergy for the New Church founded by Emanuel Swedenborg. Separate schools for boys and girls began in 1881 and 1884, respectively. Their main purpose was to strengthen their students’ ties to the faith, and for many years all of them belonged to the New Church. The school separated boys and girls in classes that were deemed gender restrictive but mixed them in other subjects. Students not only took religion classes but also attended church services on a regular basis. Among private schools in the region, it enrolled by far the largest proportion of low-income students in 2007 (see chart in the image gallery at right).

Episcopal Schools

Men founded the academies associated with the Episcopal Church in greater Philadelphia. They became more diverse over the years, enrolling girls in most cases as well as some minority and low-income students. William White, the first Episcopal bishop of Pennsylvania and the moving force behind the creation of the Episcopal Church in the United States, founded Episcopal Academy in 1785. Located in the city at first, it followed its mostly affluent constituency to suburban Lower Merion in 1921. In 2008, the school pulled up stakes once again, relocating to a larger campus in Newtown Square, Delaware County. Its students were still required to attend chapel, but religious observance in its daily life paled by comparison to academic rigor and college acceptance.

St. Andrew’s School (also Episcopal) in Middletown, Delaware, is a boarding school for college preparatory students with an emphasis on the liberal arts. Founded in 1929 by A. Felix du Pont, a member of Delaware’s immensely wealthy Du Pont family, it was intended to give a superior education to boys of all socioeconomic backgrounds. The school’s large endowment has allowed it to be generous with financial aid for low-income students.

Akiba Hebrew Academy

As the anti-Semitism that once characterized Philadelphia culture subsided in the second half of the twentieth century, Jews gained access to many private schools that had previously been off limits to them. But before such barriers came down, Rabbi Joseph Levitsky, among others, established Akiba Hebrew Academy. Opened at the Young Men’s/Young Women’s Hebrew Association on South Broad Street in 1946, it moved to North Philadelphia (Strawberry Mansion) in 1948, Wynnewood six years later, and Merion Station in 1956. The wealth amassed by Philadelphia lawyer and philanthropist Leonard Barrack made possible another move, this time to Bryn Mawr in 2008, where it became known as the Jack M. Barrack Hebrew Academy. Like many of the Christian preparatory schools in southeastern Pennsylvania, it was mobile but perhaps because it was not founded until after World War II, it was also coeducational from the beginning.

As the anti-Semitism that once characterized Philadelphia culture subsided in the second half of the twentieth century, Jews gained access to many private schools that had previously been off limits to them. But before such barriers came down, Rabbi Joseph Levitsky, among others, established Akiba Hebrew Academy. Opened at the Young Men’s/Young Women’s Hebrew Association on South Broad Street in 1946, it moved to North Philadelphia (Strawberry Mansion) in 1948, Wynnewood six years later, and Merion Station in 1956. The wealth amassed by Philadelphia lawyer and philanthropist Leonard Barrack made possible another move, this time to Bryn Mawr in 2008, where it became known as the Jack M. Barrack Hebrew Academy. Like many of the Christian preparatory schools in southeastern Pennsylvania, it was mobile but perhaps because it was not founded until after World War II, it was also coeducational from the beginning.

Nonsectarian Private Schools

Besides the schools with religious ties, nonsectarian private schools have been in the region for many years. Some always were, while others have become college preparatory. A few moved to suburbs during the twentieth century. Like several of their sectarian counterparts—Abington Friends (1966), St Andrews School (1973), Episcopal Academy (1974), and Penn Charter (1980) — they began shifting from single-sex to coeducation in the 1960s and 1970s. They did so not only because of changing attitudes about gender roles, but also because of their dependence on tuition income. In 1962 the average cost to attend one of them was about $1,000 per year, far more than what most families could pay. Although the decision to go coeducational was often divisive, it was no longer advisable or even feasible for them to deny access to half the school-age population. Over the next forty years many increased their enrollment, even as their tuition grew by as much as 2500 percent.

The oldest nonsectarian private school to survive into the twenty-first century is Germantown Academy. Established in 1759 as the Germantown Union School, it was initially located in the place for which it was named. It moved to a new suburban campus (Fort Washington) in 1965 and became coeducational. The Hill School in Pottstown, Montgomery County, was founded as a boarding school in 1851. Its founder, the Reverend Matthew Meigs, was a Presbyterian minister, but the school was never affiliated with that denomination or any other. Originally known as “The Family Boarding School,” its board of directors renamed it the Hill School—a reference to its elevated site—when academic excellence and college preparation became its primary mission. Originally for boys only, the school was a latecomer to coeducation, admitting girls for the first time in 1998. The Haverford School, on the other hand, chose to remain for boys only. Founded in 1884 as the Haverford College Grammar School, it acted as a feeder for the college for many years. It was under the care of the college’s board of managers until 1916.

The oldest nonsectarian private school to survive into the twenty-first century is Germantown Academy. Established in 1759 as the Germantown Union School, it was initially located in the place for which it was named. It moved to a new suburban campus (Fort Washington) in 1965 and became coeducational. The Hill School in Pottstown, Montgomery County, was founded as a boarding school in 1851. Its founder, the Reverend Matthew Meigs, was a Presbyterian minister, but the school was never affiliated with that denomination or any other. Originally known as “The Family Boarding School,” its board of directors renamed it the Hill School—a reference to its elevated site—when academic excellence and college preparation became its primary mission. Originally for boys only, the school was a latecomer to coeducation, admitting girls for the first time in 1998. The Haverford School, on the other hand, chose to remain for boys only. Founded in 1884 as the Haverford College Grammar School, it acted as a feeder for the college for many years. It was under the care of the college’s board of managers until 1916.

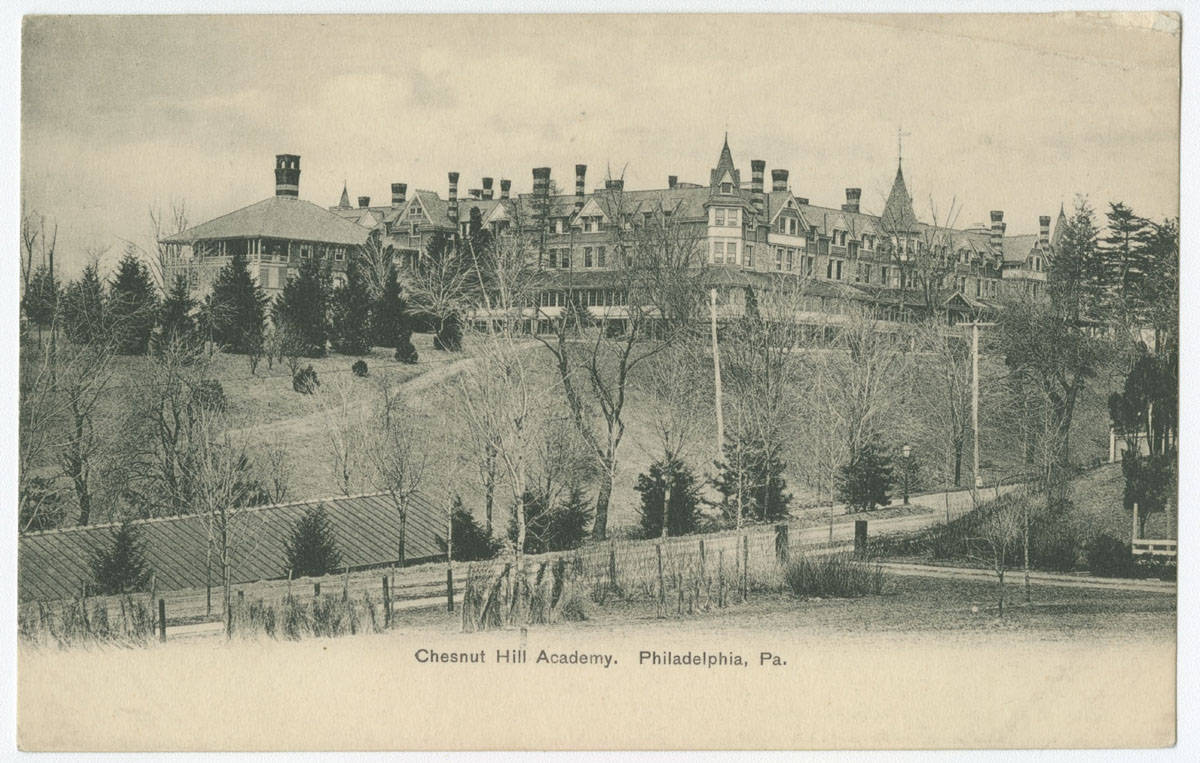

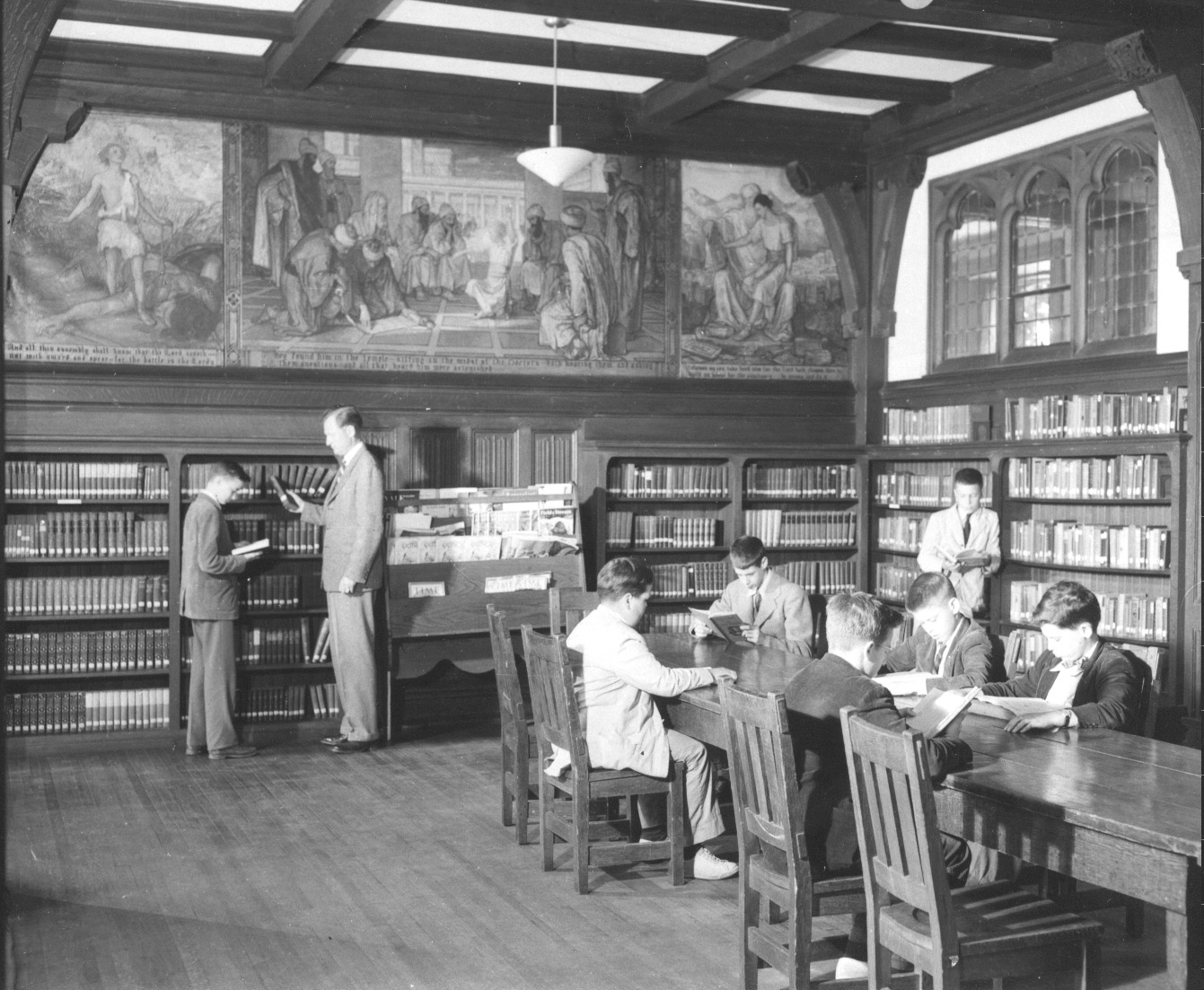

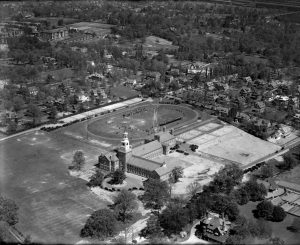

Chestnut Hill, an elite residential neighborhood in northwest Philadelphia, has been home to two selective private schools since the mid-nineteenth century. Opened in 1861 as a school for boys, Chestnut Hill

Academy was loosely tied to the Episcopal Church and even explored merging with Episcopal Academy. Boarders were expected to attend Sunday services at neighboring St. Martin-in-the-Fields Episcopal Church until 1934 when the Depression forced the boarding department to close. Thinking that this fashionable neighborhood needed a girls’ “finishing school,” two southern women, Ann Bell Comegys and Jane Erwin Bell, founded Springside School in 1879. After occupying several sites in Chestnut Hill for nearly eighty years, it moved in 1957 to the front lawn of Druim Moir, the former home of multifaceted entrepreneur and real estate developer Henry Howard Houston. By then, its student body had become more diverse thanks to the gradual modification of its neighborhood orientation. Almost half its students now lived outside Chestnut Hill, but these girls often had trouble fitting in. Because the two schools were adjacent, they increasingly entered into joint ventures, beginning in the 1960s, and finally merged completely in 2011, becoming Springside Chestnut Hill Academy.

Nonsectarian Schools for Girls

Nonsectarian private schools for girls appeared in the Main Line suburbs at the end of the nineteenth century. Educating them meant limiting their exposure to some of the subjects taught to boys, such as science and math. It also meant a curriculum that featured languages, art, music, and the social graces. Florence Baldwin founded the institution that bears her name in 1888 as an unofficial preparatory school for the academically rigorous Bryn Mawr College. One year later the Shipley sisters located their new school across the street from Bryn Mawr College to drive home the point that they, too, intended to prepare young women for college, not just marriage. Both schools accepted boarders as well as day  students for many years but eventually closed their boarding departments. Shipley went one step further, becoming coeducational in 1984. The Agnes Irwin School, which opened its doors in 1869, has never admitted boys. Like so many of its counterparts, it moved out of Philadelphia, settling in Wynnewood in 1933 and then in Rosemont twenty-eight years later. Like Springside eventually did, these three schools downplayed high society, stressing higher education instead.

students for many years but eventually closed their boarding departments. Shipley went one step further, becoming coeducational in 1984. The Agnes Irwin School, which opened its doors in 1869, has never admitted boys. Like so many of its counterparts, it moved out of Philadelphia, settling in Wynnewood in 1933 and then in Rosemont twenty-eight years later. Like Springside eventually did, these three schools downplayed high society, stressing higher education instead.

The adoption of coeducation by many of these private schools in the second half of the twentieth century leveraged their commitment to college preparation. It reinforced the idea that academic achievement was their prime consideration. But even those schools that remained single-sex had to have a demanding curriculum. They supplemented languages, science, and mathematics with opportunities for self-expression (e.g. the performing arts) in a robust extra curriculum. Some added community service (aka service learning) because many colleges looked for evidence of this in applicants. Informed by federal legislation (Title IX), others introduced a girls’ sports program, or expanded it, building on their long history of boys’ interscholastic competition. The athletic rivalry between Germantown Academy and Penn Charter dates to 1886. All of these improvements have required constant fund-raising.

Along with coeducation, minority recruitment, and the elimination of religious restrictions in admissions, the focus on college preparation helped to make selective private schools more alike than different. Even those for girls operated by Catholic religious orders were not able to resist this trend. All of these schools survived, despite their high cost, because they had some important advantages. Their facilities were outstanding and their reputations excellent. Like all private schools, they were less subject to government regulation, freeing them, for example, from state teacher certification requirements and the standardized tests imposed by federal law. They set their own academic standards. Such private schools have been criticized because they do not participate in the grand democratic experiment that public education represents. But they offer to those who can afford them an attractive alternative to the public schools—especially those in Philadelphia, Chester, and Camden—that many regarded as failing.

David R. Contosta is the author of many books and articles on Philadelphia history, such as Philadelphia’s Progressive Orphanage: The Carson Valley School (1997). William W. Cutler III has authored many publications on the history of education in Greater Philadelphia. His most recent is “Outside In and Inside Out: Civic Activism, Helen Oakes and the Philadelphia Public Schools, 1960-1989,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography CXXXVII (July 2013), 301-324.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Springside Chestnut Hill Academy president discusses sustainability efforts at school (WHYY, October 24, 2012)

- Springside Chestnut Hill Academy adds leadership training to its curriculum (WHYY, March 22, 2012)

- New leader wants to give elite Philly private school 'public purpose' (WHYY, November 17, 2016)