Public Education: High Schools

Essay

From one of America’s earliest public secondary schools to the large, neighborhood high schools of the early twentieth century and sprawling suburban campuses after World War II, through later experiments aimed at restructuring and reforming urban high schools, Greater Philadelphia has been notable in the development of secondary education in the United States.

Central High School, established in 1838 at the current location of the Wanamaker Building, on Juniper and Market Streets, provided the sons of middle-class shopkeepers and artisans with the skills and credentials they believed they needed for social mobility in a rapidly changing industrial society. Part of the movement for tax-supported common (public) schools in the mid nineteenth century, Central dramatized a tension, still evident in the region today, between the ideal that public schools would provide democratic opportunity and the reality of unequal experiences. Central’s entrance exam and its monopoly over boys’ secondary education epitomized public education in Philadelphia, though it served only a tiny segment of the city’s population. Over the next half century political pressures led to expanded access as well as the establishment of competing high schools, starting with Central Manual Training (on the corner of Seventeenth and Wood Streets) in 1885. Girls’ high school education proceeded on a parallel track, when Girls’ Normal School for teacher preparation, founded in 1848, became Girls’ High and Normal School twelve years later. The school occupied a grand building at Seventeenth and Spring Garden Streets in 1876, and it continued to be the home of the Philadelphia High School for Girls after the two became separate institutions in 1893.

Spurred in part by Philadelphia’s Centennial Exhibition (1876), manual training schools introduced mechanical arts into the curriculum, though the academic focus remained strong, and access was not widespread. In the early twentieth century, however, and especially after 1920, the high school became a mass institution. At a time of upheaval stemming from immigration and industrialization, educators and government officials began to expand public education and look to the high school as a vehicle for socializing all youth.

Fifteen New High Schools

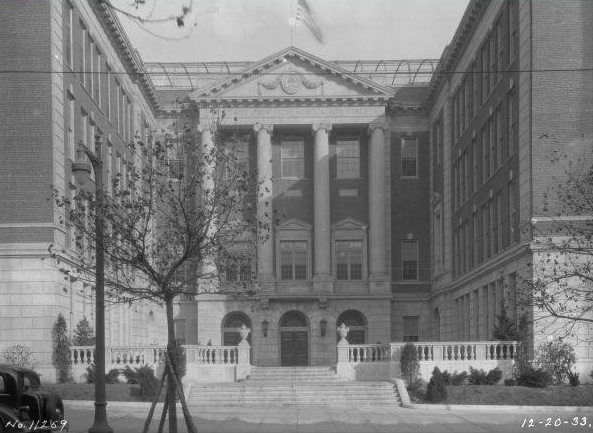

In the early twentieth century, high schools constructed in Center City Philadelphia and in Camden, New Jersey, represented the cutting edge of innovation in education. Between 1911-1939, under a newly centralized school board, the School District of Philadelphia built fifteen neighborhood high schools, including West Philadelphia High School in 1912 (at Walnut Street between Forty-Seventh and Forty-Eighth Streets) and South Philadelphia High School in 1915 (on Broad Street and Snyder Avenue). The building program was notable for its style as well as its scale. Architect Irwin T. Catharine (1883-1944) supervised the design and construction of all public high schools built in Philadelphia between 1923 and 1937, which were similar regardless of what neighborhood or ethnic groups they served. Referred to as “cathedrals of learning,” these massive, ornately-decorated structures symbolized the city’s expanded commitment to secondary education (and influenced school construction in the suburbs). At West Philadelphia High, which occupied an entire city block, students passed through castle-like entrances intended to inspire them with stone carvings of scholarly equipment such as books and pens. Boys and girls entered separate, identical halves of the building, though these were joined for co-education in 1927. Camden High School (established in 1891 as the Camden Manual Training and High School) was built in a similar style.

The new high schools were not only numerous, large, and architecturally grand; they also offered a “comprehensive” program that school leaders touted as meeting the needs of all youth. As the system expanded to include new ethnic and socioeconomic groups, educators broadened the academic and manual curriculum to include trade training for specific occupations. For example, John Bartram High School, named for the eighteenth century Philadelphia botanist, opened in 1939 (on Sixty-Seventh Street and Elmwood Avenue) with a greenhouse, electrical shops, and an entire floor devoted to commercial topics such as retail salesmanship. Comprehensive high schools like Bartram exemplified a new era of mass secondary education, defined by differentiated curricular tracks taught under one large roof.

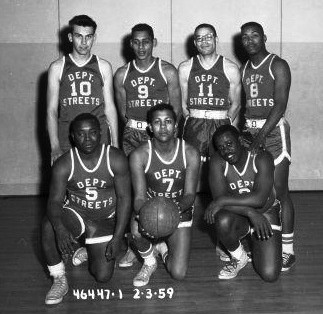

Between 1920 and 1945, curricular expansion and a lack of jobs for teenagers, especially during the Depression, helped spur a dramatic increase in rates of high school attendance. This trend intensified after World War II as the rise of a postindustrial economy helped make education more central to American life. Yet, even as going to high school became almost commonplace, the quality and outcomes of education varied tremendously. After 1945, as southern blacks migrated to Philadelphia and whites moved out of the central cities to newly developed sections of Northeast Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania suburbs, or South Jersey, high schools became more segregated. In a context of rising poverty and urban decline, the comprehensive high schools of Philadelphia and Camden went from being models of innovation to sites of underachievement, disorder, and protest, while the standard for educational excellence passed increasingly to the suburbs.

Outside City, Fewer High Schools

The suburbs had not always set the pace. In the first half of the century, public high school options outside of Philadelphia had been concentrated in affluent and/or populated areas, such as Lower Merion, Media, and Cheltenham in Pennsylvania and Haddonfield, Paulsboro, and Moorestown in New Jersey. These and other districts had high schools that served their own residents as well as some students from smaller districts that paid tuition for them to attend. Delaware was largely rural and educationally backward, though state leaders and the industrialist Pierre S. du Pont (1870-1954) did much to expand educational opportunities after 1920, including the modernization of two notable high schools in the city of Wilmington: Pierre S. du Pont High School, a landmark Georgian structure built in 1935 and recently renovated as a middle school, and Howard High School, one of some eighty African American schools that du Pont built or rebuilt in Delaware with his own money.

Increasing suburbanization after World War II transformed the educational landscape. Districts with existing high schools expanded or rebuilt them, as Moorestown did in 1962. Meanwhile, population growth led some localities to construct new high schools, sometimes at a dizzying pace. In 1957, for example, residents of Cherry Hill, New Jersey, stopped paying tuition to send their children to Moorestown High School, and the district opened a school of its own, Delaware Township High School (later Cherry Hill High School West). Within weeks the district hired architects to double the capacity of the new building, and within a decade it dedicated another new high school, Cherry Hill East (1968). In another trend, small districts consolidated or cooperated to create regional high schools; Garnet Valley High School (1966), for example, served what previously had been three separate school districts in Delaware County, Pennsylvania. Ten regional high school districts were operating in Burlington (3), Camden (4), and Gloucester (3) counties in New Jersey by 1976. And finally, after 1960, the Archdiocese of Philadelphia shifted its focus from the central city to suburbs like Springfield, in Delaware County, where Cardinal O’Hara High School opened in 1963.

The new suburban high schools were still comprehensive high schools of the sort that had been pioneered in the city, but they tended to have a more pronounced focus on college-preparatory academics, and they set a new standard and style in school design. Instead of imposing edifices, schools such as Harriton High School in Lower Merion (1958) epitomized a popular new emphasis on campus-type layouts and extensive athletic fields.

Suburban high schools were not immune from the disorder and violence that plagued urban schools in the 1960s and 1970s, and independent or private high schools—always an important presence in Greater Philadelphia—attracted families even in prosperous suburban districts. In the late 1970s, for example, Friends Schools in Haddonfield and Moorestown, New Jersey enjoyed rising popularity. Still, in 1970 the educational advantages of the suburbs were indicated by U.S. Census data showing that in central Philadelphia, even after decades of expansion in access to high school, only forty-two percent of the adult population had a high school diploma, compared to sixty-eight percent in the Philadelphia suburbs. By 2013, high school graduation rates in the School District of Philadelphia had risen to about sixty percent (up about twenty percent since the mid-1990s), yet rates in many suburban districts continued to be substantially higher. Suburban high schools continued to attract families seeking strong academics, although private tuition and real estate prices limited access, a problem that was highlighted by reports of families who used illegitimate addresses to gain admission to favored high schools. At least one district—Pennsauken, New Jersey—hired a full-time investigator to catch such violators, who appeared to be coming from Camden.

Into the twenty-first century, the academic performance of high schools in Greater Philadelphia remained dramatically uneven, though dissatisfaction with Philadelphia’s comprehensive high schools generated reforms with influence in and beyond the region. Since the 1960s, these have included the Parkway Program (1967), a briefly influential “school-without-walls” that aimed at tapping the educational resources of the city; career academies, a school-within-a-school initiative introduced in the 1980s that blends academic and applied learning related to particular careers; and ongoing efforts to restructure large high schools into academically-focused charter schools run by various entities, private as well as public. By 2013, the shift toward charters had contributed to long-term enrollment declines at some large comprehensive high schools, leading to painful decisions to close some of those schools, including, Germantown High School (1914), one of the city’s oldest.

John P. Spencer is Associate Professor of Education at Ursinus College. He is the author of In the Crossfire: Marcus Foster and the Troubled History of American School Reform (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012).

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- On the scene for the last day of Germantown High School's life (1914-2013) (WHYY, June 21, 2013)

- For many Philly families choosing high schools, it's either magnet or charter (WHYY, March 11, 2014)

- Philadelphia School Partnership gives $2 million to new public high school (WHYY, March 18, 2014)

- Will prosecuting parents help solve Philly's problem with chronically truant students? (WHYY, April 19, 2014)

- Young Philly football star's transfer stirs bad blood between two schools (WHYY, July 9, 2014)

- Pending deal on former school building catches Germantown High neighbors off guard (WHYY, September 19, 2014)

- Nearly half of Camden's graduates get diplomas by appeal (WHYY, February 9, 2015)

- Students begin using recording studio donated by Drake (WHYY, March 10, 2015)

- Vaux High School reopens as part of Sharswood revival (WHYY, September 5, 2017)