Public Education: Suburbs

Essay

In the second half of the twentieth century, many parents moved their families out of Philadelphia, Camden, or Wilmington so that their children could enroll in suburban public schools because they perceived them to be better than their urban counterparts. Before then, many believed that the best public schools were urban and that rural schools were inadequate. But as many rural communities became suburban, they created comprehensive public school districts with programs and facilities that matched or exceeded those found in the region’s cities.

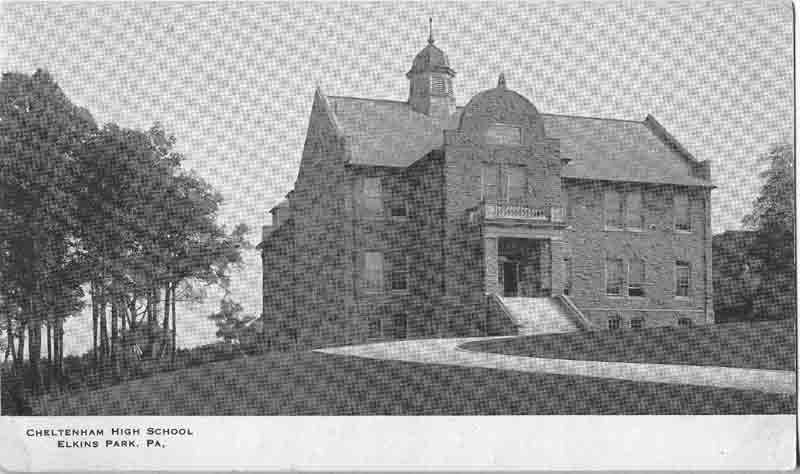

More often than not, the rural districts that upgraded their public schools were in communities that began to suburbanize as early as the 1870s with the advent of commuter railroads and, later, electric trolley lines. The residents of these communities wanted urban benefits and services — paved roads, sewer lines, and, above all, comprehensive systems of public education. Audubon, Collingswood, and Haddonfield, in Camden County, New Jersey, and Abington, Cheltenham, and Lower Merion, in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, acted on such expectations. So, too, did those who lived in the several small but thriving centers of commerce and industry outside the region’s big cities, in places like Norristown, Pottstown, and Conshohocken in Pennsylvania and Gloucester City in New Jersey.

Rural Districts Become Suburban

Between 1895 and 1920 many rural school districts in Montgomery County became suburban. In 1897 there were 498 public schools and fifty-five public school districts in the county; forty-four of these operated only one-room schools. By 1916 the number of districts operating just one-room schools had been reduced to ten; the total number of public schools had been reduced by more than 200; and the number of districts operating high schools had risen from a handful to twenty-one. Not surprisingly, these included Norristown (with 474 students in high school), Pottstown (380), and Conshohocken (101), along with Abington (205 students), Cheltenham (273), and Lower Merion (336). Jenkintown and Narberth did not have separate high school buildings in 1916; instead, they set aside rooms for high school classes in their elementary school. But the suburban die was cast, and by 1930 there were high schools in thirty-six of the county’s sixty-six public school districts.

The fifty years that followed the end of World War I might be called the era of suburbanization in Greater Philadelphia. Population grew substantially in the four Pennsylvania and three New Jersey suburban counties between 1920 and 1940, and the pace accelerated after World War II. In South Jersey, for example, population in Burlington, Camden, and Gloucester counties grew more than twice as fast in the twenty years after 1940 (+77%) as it did in the twenty years before (+33%). Some of this demographic growth resulted from the Baby Boom that began in 1946. But some of it came about because many young families relocated, and they often settled far from the city, renting or buying housing in newly developed communities. In 1960, for example, more than one-third of Burlington County residents had been living in their present house for no more than two years. Levitt and Sons persuaded many white-collar and even some blue-collar families to uproot by building planned communities for them in both Bucks (1951) and Burlington (1958) counties.

Most public school systems were unprepared for this demographic shift. Those in Pennsylvania had some time to adjust because the effect was modest at first; between 1954 and 1958 public school enrollment in the four Pennsylvania counties surrounding Philadelphia grew by just eighteen percent. Over the next twelve years, however, it increased by more than two-thirds, climbing from 228,551 to 384,200 students. The comparable numbers for the three New Jersey counties across the Delaware River from Philadelphia are staggering. Public school enrollment in Burlington, Camden, and Gloucester counties nearly tripled between 1950 and 1970, soaring from just over 78,000 to just under 211,000 students. The lion’s share of this growth (60 percent) took place in Burlington and Gloucester counties where the population before 1945 had been small and scattered.

These numbers alarmed educators and reformers not only because none of the school districts in these suburban counties had enough teachers or classrooms but also because many districts still functioned as they always had. In 1945 more than a few in both New Jersey and Pennsylvania relied on supervising principals rather than superintendents. Several did not operate their own high schools, paying for their students to go elsewhere. But by far the most vexing problem was the persistence of small school districts. When Harvard University’s former president James Bryant Conant loudly complained in 1959 that far too many communities in the United States had public high schools that were too small to offer sufficiently rigorous academic programs, his words described the Greater Philadelphia suburbs. Most of their residents still believed that smaller was better in public education or at least not bad enough to justify the consolidation through reorganization of small school districts. New Jersey codified this expectation by requiring local school boards to submit their annual budgets to the voters for approval by referenda.

Push for Modern Curriculum

Reorganization was not a new idea in 1950. As early as the turn of the twentieth century many school reformers advocated it. They wanted to eliminate the one-room, one-teacher school and form high schools that offered a modern curriculum including contemporary foreign languages, social studies, physical science, bookkeeping, and stenography. They wanted schools capable of housing a varied extra curriculum, including interscholastic athletics for boys and in most cases girls. Small rural districts could not provide these amenities; their tax base was too small, their unit costs too high. Between 1910 and 1940 reformers made considerable progress in achieving reorganization, especially in New England and the South Atlantic states. But progress came more slowly to the Mid-Atlantic region where local loyalists resisted.

Delaware is a case in point. The crucial variable there was not the economic disparity between Wilmington, its biggest city, and the rest of the state but the political gap between Dover, its capital, and its rural school districts. The idea to reorganize came from the state’s first Commissioner of Education, Charles A. Wagner (1863-1924); his boss, Governor John G. Townsend (1871-1964), ran with it. At Townsend’s behest the legislature instructed the governor to appoint a school reform commission in 1917. It devised a new school code that put considerable power in the hands of county school boards. One of the most powerful men in the state, industrialist and philanthropist Pierre S. du Pont (1870-1954), endorsed this reform, but in the face of fierce opposition from local school districts the legislature reversed itself in 1921, dismantling the county school board system. Once again, public education would be overseen by local authorities working with the state Board of Education. But the unintended consequence of this reform was to increase the power of the state board and the state Commissioner of Education.

The state board hoped to modernize public education through reorganization. At the time there were 395 incorporated school boards and unincorporated school committees in Delaware. Many supervised just one school. The state’s first consolidated rural district (Caesar Rodney) had been formed south of Dover in 1916. By 1921 there were thirteen such districts, and the reformers hoped that consolidation would make it possible for more rural students to get a high school education. Not including Wilmington, there were only 116 students in the state poised to graduate from a four-year public high school in 1918. Over the next twenty years the state commissioner convinced some rural districts to accept consolidation in exchange for help from Dover with teacher salaries and pupil transportation. In 1953 the state board drafted legislation to reduce the number of school districts from 105 to fifteen, but rural school consolidation did not really come to pass until the General Assembly adopted the Educational Advancement Act in 1968. It cut the number of school districts in the state from sixty to twenty-six. Meanwhile, reorganization barely touched the lives of Delaware’s African American children before the 1970s because until then the state maintained a dual system of public education. Only Howard High School in Wilmington was available to black students while school segregation remained widespread. In 1965 the state board of education ordered the closure of twenty-five “Negro” districts, but most of them were in rural communities.

In New Jersey reorganization reshaped the map of public education following World War II, but the state’s tradition of local control affected the way this occurred. Perhaps because New Jersey lacked a major metropolis, most people had no experience with anything other than “neighborhood” schools. Not surprisingly, new school districts formed when population grew. Between 1900 and 1970 the number of school districts in the state rose from 395 to 576. Camden County’s total stood at thirty-six in 1950, and this number did not change over the next twenty years because the fastest suburban development in South Jersey was taking place elsewhere. Burlington and Gloucester counties added seven districts in the same period. In many of them home buyers found a four-year public high school, one of the features they wanted most in a suburb. In the three-county region the number of school districts with a high school almost doubled between 1950 and 1976 (from 21 to 41) with Burlington (7) and Gloucester (8) counties registering the largest increases. Twelve of these were regional high schools operated by regional high school districts. For many years families living in a rural district without a high school sent their children to one in a nearby suburban district. In Camden County, for example, they sent them to Merchantville, Haddon Heights, or Haddonfield. But now rural and suburban families could send their children to one of twelve high schools operated by a regional high school district (RHSD). The first two of these, Rancocas Valley RHSD in Burlington County and Lower Camden County RHSD were formed in the 1930s; the rest came to life after World War II. The reason for them, according to the New Jersey State Department of Education, was that they “bring together a sufficient number of pupils and financial resources to offer a broad and comprehensive educational program.” Collaboration, not consolidation, was New Jersey’s response to the people’s demand for public secondary education.

Pennsylvania Takes the Lead

Pennsylvania took a different approach, committing itself to school reorganization after World War II. Larger than New Jersey and Delaware combined, it had 2,544 school districts in 1945, nearly ten percent of which (240) were in Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery counties. Thirty years later the number of school districts in Pennsylvania had been drastically reduced to fewer than 600. In Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery counties there were sixty-one (as before, about ten percent), but they were now educating more than twice as many students. The justification for reorganization was partly financial. Even in Montgomery County the tax base in some suburban communities was not large enough to pay for an educational program with all the essentials, much less any extras. The state could have used its equalization subsidy program to compensate for the differences, but it chose to help less affluent communities by achieving economies of scale.

Lawmakers knew that Pennsylvania had too many small school districts as early as 1854 when they first made provision for collaboration among them. At the beginning of the twentieth century the commonwealth adopted a new school code that authorized the use of state aid for student transportation in districts that collaborated or consolidated. But it was not until the late 1940s, when many Americans realized that public education had been neglected for far too long, that the Pennsylvania legislature mustered the political will to attack the problem. In 1947 it passed a law that gave the county boards of school directors, created in 1937, the “power and duty” to prepare long-range plans for eliminating districts with no or only a few students. It also set aside money to give school districts an incentive to collaborate, but a commission appointed by Governor George Leader (1918-2013) concluded in 1960 that such financial incentives were ineffective. Leader’s successor, David L. Lawrence (1889-1966), repeated the call for reorganization because he considered the real estate tax base in many rural and even some suburban districts to be insufficient to support a modern educational program. Some of those districts (such as those in Jenkintown Borough and Bristol Township) were in the Philadelphia suburbs. The legislature responded in 1961, passing legislation (Act 561) to reduce the number of districts, but quickly repealed it after Republican William Scranton (1917-2013) defeated Democrat Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974) in the 1962 gubernatorial election. Once in office, Scranton endorsed a watered-down version of Act 561 (Act 299) that retained its predecessor’s minimum enrollment provision of 4,000 students but allowed for numerous exceptions based on topography, pupil population, community characteristics, transportation, and educational quality.

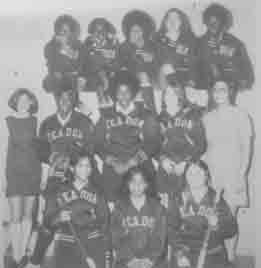

Perhaps the most outspoken opponents of school district reorganization came from the Philadelphia suburbs. Jenkintown’s Wilmot E. Fleming (1916-1978) believed that the best small districts should remain independent. Others argued that consolidation would lead to higher taxes or decline of community spirit and loss of local control. In 1966 State Senator Clarence Bell, a Republican from Delaware County, warned that reorganization would eventually lead to the formation of a metropolitan school district, an idea that Richardson Dilworth floated while he was the president of the Philadelphia School Board. If such a district had been created, it would have brought a wave of African Americans from the city to the suburbs, a prospect certain to upset many of the whites living there. They did not see the minority children already in their midst, perhaps because they lived in neighborhoods and patronized schools that were mostly segregated. This discrimination led to civil rights protests in places like Mt. Holly, New Jersey, and Abington, Pennsylvania. It even convinced the Lower Merion School District to close the Ardmore Avenue Elementary School in 1963 because it was segregated. But it also led to a long and bitter fight against school reorganization – in Delaware County especially.

Just beyond West Philadelphia, southeastern Delaware County began to suburbanize at the beginning of the twentieth century. Public transportation allowed many of its white-collar and blue-collar residents to commute to jobs in Chester or Philadelphia. Some of the area’s public school districts took on suburban characteristics. In 1908, for example, the Darby Borough district replaced its supervising principal with a superintendent. It also opened a four-year high school, as did the Lansdowne Borough School District in 1914. The population of southeastern Delaware County, which rose rapidly at the beginning of the twentieth century, leveled off during the Great Depression but started growing again once prosperity returned. Folcroft’s mostly white population increased by twenty-six percent in the 1950s. Public school enrollment did not increase as fast, in part because many young families chose the leafier suburbs of Bucks and Montgomery counties instead.

Shifts in Racial Balance

Between 1900 and 1960 the African American proportion of the population in Delaware Country shrank from ten percent to seven percent. But in places like Darby Township and Yeadon Borough there were already enough black families to deter prospective partners in any reorganization effort. In 1964 the county’s plan for reorganization faced opposition because it proposed to combine three school districts that were almost exclusively white – Collingdale (99.7 percent), Folcroft (100 percent), and Sharon Hill (98.5 percent) – with two that were significantly black, Darby Colwyn (22.1 percent) and Darby Township (68.2 percent). Responding to an appeal from the white districts, the State Board of Education placed Darby Colwyn in another reorganized district. The Delaware County Board of School Directors approved the consolidation of the Folcroft, Sharon Hill, Collingdale, and Darby Township school districts in 1968, and subsequent appeals that eventually went all the way to U.S. District Court failed to prevent the formation of the Southeast Delco School District. But discrimination persisted because minority students living in the southern portion of Darby Township were bused past all-white schools in nearby Folcroft and Sharon Hill to schools in the northern part of Darby Township that already had many black students.

The elaborate appeals procedure set up by the state in 1968 (Act 150) slowed but did not prevent reorganization from being implemented. In 1975 there were thirteen local and forty-eight regional school districts in Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery counties; many of the latter emerged out of cooperative arrangements, known as “jointures,” which had been in place for years. For example, the eight districts in Montgomery County that had participated in the North Penn Jointure for grades seven through twelve stayed together as the North Penn School District. Its 11,402 students in 1973 made it one of the largest in Greater Philadelphia. But some small districts avoided reorganization, especially in Montgomery County, because they met the state’s requirements for independence. Despite never enrolling more than 828 students, the Jenkintown School District was not forced to merge with either Abington or Cheltenham because its leadership convinced county and state officials that it had the economic resources and the educational standards to remain self-governing.

By the early 1980s segregation had become a regional problem in Greater Philadelphia because the public schools in Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Camden now had such a high proportion of black students. There were simply not enough whites enrolled in these urban school systems to achieve racial balance. Aware of this disparity, most educators and politicians ignored it. Change did occur in Delaware when the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed a District Court decision (Buchanan v. Evans, 1975) that led to the consolidation of all the public schools in New Castle County where Wilmington is located. Formed in 1981, the Brandywine, Colonial, Christina, and Red Clay Consolidated school districts brought the black children of the city together with white children living in its suburbs. But such sweeping changes may have helped convince at least some people that public education was failing not just in the region’s cities but everywhere. Whether urban or suburban, public schools increasingly found themselves being compared unfavorably with private schools, charter schools, and even home schooling.

The crisis of confidence in public education that began in the 1980s stemmed in part from the fact that suburban public schools were not able to escape the problems of their urban counterparts. Given a choice, suburban educators would immunize their schools against violence and substance abuse. All their students would excel on standardized tests and be admitted to college. None would be victimized by the ravages of poverty or the sting of racism. But this is not how public education works, even in the most affluent suburbs.

Public schools are open and free to all – by definition. Those in charge cannot ignore at-risk students, no matter what the problem. Children with special academic needs or debilitating personal problems are not geographically bounded, and their right to a “thorough and efficient” public education is legally protected. But some previously all-white suburbs had to contend with more equity issues than others at the end of the twentieth century because by then they had absorbed enough nonwhite residents to make race a significant issue in their public school systems. Consider, for example, the Cheltenham School District in Montgomery County, whose minority population had become big enough by the mid-1990s to attract attention. In 1996 the Cheltenham School Board decided to achieve better racial balance by busing some elementary students. This decision was denounced – not by white, but rather by some black parents, who accused the board of racism because its busing program increased one school’s proportion of white students. The board members who made this decision did not anticipate such opposition, but they stuck by it because they believed it would make the Cheltenham public schools better for everyone.

Over the course of the twentieth century the relationship between suburban and urban public schools in Greater Philadelphia flipped. Suburban schools at first emulated their urban counterparts and hoped to be compared favorably with them. When urban public education fell on hard times, suburban schools ran away from such comparisons. But suburban and urban public schools could not run away from each other not only because they shared the same fundamental characteristics but also because they served a region that was itself becoming increasingly diverse and interdependent.

William W. Cutler III is Professor of History, emeritus, at Temple University. He was a member of the Jenkintown Board of School Directors for eight years (1995 to 2003), the last two as president. Catherine D’Ignazio holds a Ph.D. in Urban Education from Temple University. She is an adjunct professor of History at Rutgers University, Camden campus.

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History