Puerto Rican Migration

Essay

Puerto Ricans migrated to the Philadelphia area in search of better economic opportunities. A small stream of migration prior to the twentieth century grew during the two world wars, with many more migrants arriving from the 1950s onward. Many families settled permanently in the region, where their lives intertwined with Black and white residents and their labor supported the agricultural and manufacturing sectors.

Small pockets of Puerto Rican settlement existed in Philadelphia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Long-standing business relationships between the island and city merchants, especially in the sugar trade, provided personal contacts and direct transportation routes. Itinerant cigar makers, railroad workers, and a smaller number of students and professionals also reached the city, aided by informal networks of family and friends. Some early migrants used Philadelphia as a base for revolutionary political critiques of Spain. They joined Cubans, Mexicans, and Spaniards to form a pan-Latino enclave of perhaps 1,500 persons by 1900. Proximity to jobs along the docks, at Baldwin Locomotive Works, and in cigar factories drew Puerto Rican migrants to three primary areas: Southwark, Spring Garden, and Northern Liberties. In these multiethnic neighborhoods, Puerto Ricans mixed not only with other Spanish speakers, but also Italian, Polish, Jewish, and African American neighbors.

The region’s Puerto Rican population grew quickly due to regional labor shortages during World War I, with many new arrivals to Philadelphia moving into subdivided housing stock or boarding houses. As their numbers grew, Spanish-speaking residents founded institutions including a mutual aid society, La Milagrosa Catholic Chapel, and the First Spanish Baptist Church. Staff at the International Institute (later Nationalities Service Center) also facilitated gatherings. Alongside small businesses like bodegas, these institutions supported a Spanish-speaking community that served as a nucleus for later waves of Puerto Rican migrants. In Southern New Jersey, farmers began to hire Puerto Rican workers as early as the 1920s, and a Puerto Rican enclave emerged around Linden Street in Camden.

After the Great Depression, Puerto Rican government officials increasingly encouraged migration off the island, partly to address their perception that overpopulation exceeded economic resources. Officials facilitated employment contracts, arranged air transportation, and oversaw workers through regional offices. From the early 1940s to the early 1960s, tens of thousands of Puerto Ricans became seasonal workers in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Migrants typically came from rural island areas, where they had worked in agricultural processing of sugar, coffee, or tobacco, produced home needlework, or operated light machinery. Upon arrival in the mid-Atlantic region, the majority started out on farms, while others worked for food canning companies or railroads. As U.S. citizens, Puerto Rican contract workers were not subject to deportation, and many chose to remain stateside. Some Puerto Rican women migrated to join a family member that was already established stateside, while others traveled on their own employment contracts. Finding low wages and poor housing conditions, many migrants left agricultural work relatively quickly in favor of manufacturing or service positions. Some of the population departing from the region’s farms headed to Philadelphia and Camden, while others joined the hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans in New York City, small settlements in the Lehigh Valley, or returned to the island.

Industrialization Arrives

Meanwhile, the predominantly rural and agricultural island of Puerto Rico quickly industrialized, as a massive internal migration brought families from rural areas to cities. Finding far too few jobs for the many workers displaced by declines in agriculture and home needlework, growing numbers of Puerto Ricans left the island in search of employment. Philadelphia attracted approximately twelve thousand Puerto Rican migrants during the 1950s and soon hosted the third-largest concentration of Puerto Ricans in the continental United States, while Camden drew an additional six thousand migrants. Many moved to the cities in search of manufacturing jobs. The biggest draw was the garment industry in North Philadelphia and Kensington. Others found openings at shipyards or Camden’s Campbell Soup factory. Puerto Ricans also commonly worked in restaurants, hotels, cleaning, and maintenance.

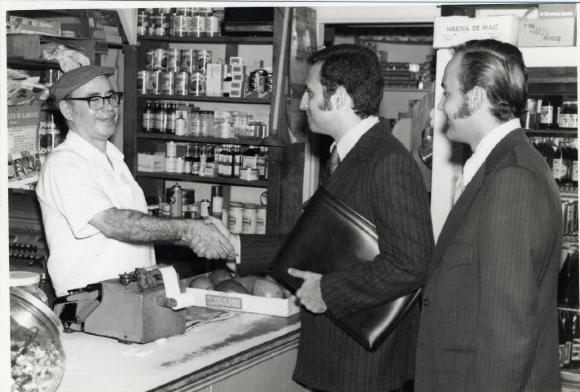

By the 1950s and 1960s, Puerto Rican migrants to Philadelphia settled primarily in the Spring Garden neighborhood and along a north-south corridor surrounding North Fifth Street. Many of their neighbors were African American families with southern roots. The clustering of Puerto Rican-owned businesses around Fifth Street and Lehigh Avenue developed into the “Golden Block” (El Bloque de Oro) retail area. Pressured by gentrification of neighborhoods close to Center City, some Puerto Rican families later settled farther north, toward Hunting Park. Others moved into West Kensington, where they sometimes faced racial violence and intimidation from remaining white residents. Across the river, Puerto Rican settlement gradually progressed into South Camden, creating friction with remaining Italian neighbors.

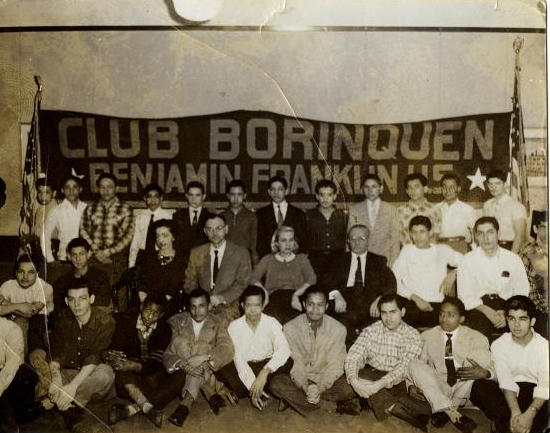

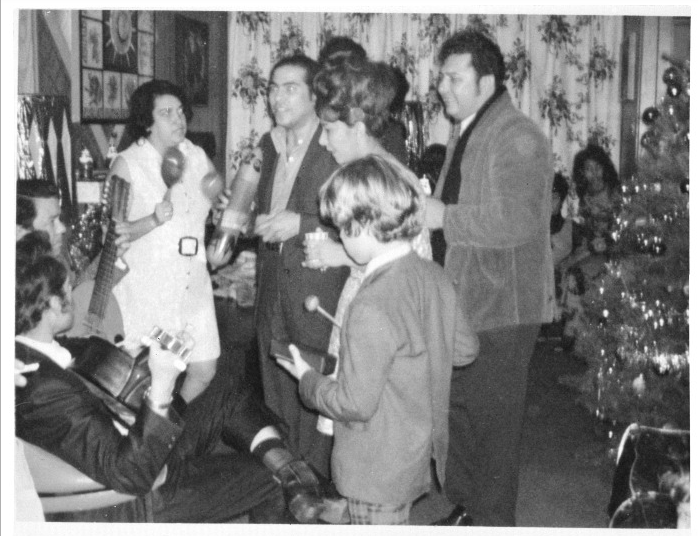

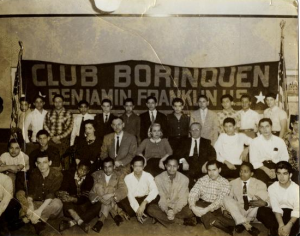

In their interactions with other city residents, Puerto Rican migrants encountered discrimination and confusion. Philadelphia officials took greater notice of the new arrivals in the mid-1950s, after white residents attacked Puerto Ricans outside a bar in Spring Garden. The Commission on Human Relations undertook studies in 1954, 1959, and 1964 to gather information on how to speed Puerto Ricans’ assimilation. Existing institutions such as Friends Neighborhood Guild, Nationalities Service Center, and branches of the Young Women’s Christian Association sought to improve services to the community. The Catholic Archdioceses also sought to reach Puerto Ricans, opening Casa del Carmen in North Philadelphia and posting a Spanish-speaking priest at Our Lady of Fatima in South Camden, which was in the process of transitioning from an Italian into a Puerto Rican parish. Meanwhile, Puerto Ricans founded their own hometown clubs and other groups, some of which united under umbrella Concilio organizations in both Philadelphia and Camden. They also made Puerto Rican culture more visible, beginning annual Puerto Rican Day celebrations in Philadelphia and Saint John the Baptist parades in Camden.

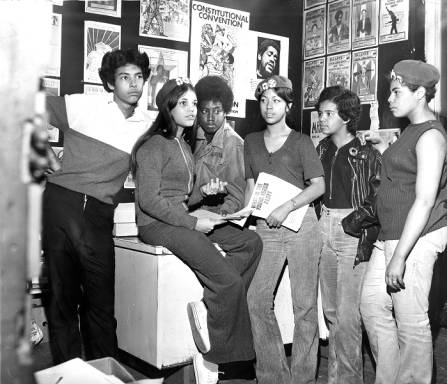

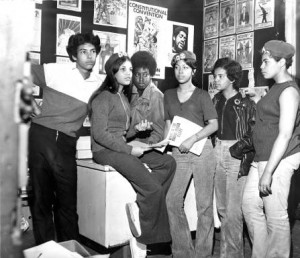

From the 1970s forward, migration from the island continued to the region even as it declined to other destinations. Local populations also grew through natural increase. By 1973, Philadelphia and Camden had an estimated 85,000 and 13,000 Puerto Ricans residents, respectively. Many families moved between the mid-Atlantic region and the island as employment and personal circumstances changed; it was not uncommon for children to attend schools in both places. The majority of Puerto Ricans still held blue-collar jobs, with about 20 percent gaining white-collar employment. The growing population took advantage of the Young Lords Party’s community programs, Aspira’s educational enrichment, and Taller Puertorriqueño’s artistic offerings in Philadelphia, while Puerto Rican Unity for Progress bolstered social services in Camden.

Community Development

In the latter decades of the twentieth century, Puerto Rican residents faced greater challenges in securing stable employment as the region deindustrialized. Neighborhood infrastructure and public services suffered from disinvestment. Nonprofit organizations including El Congreso de Latinos Unidos and Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha engaged in community development to address some of these needs in North Philadelphia, while the Puerto Rican Alliance helped channel the community’s growing political power. In Camden, the Latin American Economic Development Association (LAEDA) formed to assist small business owners. In both cities, Puerto Rican residents were particularly visible in calling attention to poor housing conditions and police brutality, at times cooperating with African American neighbors in their activism.

Beginning in the 1980s, the community’s growing political power helped elect Puerto Ricans to Philadelphia City Council and the Pennsylvania legislature. Puerto Ricans remained the largest and most politically visible Latino group in the region, but they were increasingly joined by migrants from Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and Colombia. These groups occupied their own residential enclaves and economic niches while sometimes mixing with Puerto Ricans in established Spanish-speaking organizations.

By 2010, approximately 122,000 Puerto Ricans lived in Philadelphia and an additional 24,000 in Camden. Philadelphia’s population had grown sufficiently to overtake Chicago as the second-largest mainland concentration, behind only New York City. More recent economic troubles on the island spurred additional migration to the mid-Atlantic region.

Overall, Puerto Rican migration to Philadelphia has been a reflection of economic circumstances. Workers who found an inadequate labor market on the island were attracted to opportunities in agriculture, manufacturing, and service in the mid-Atlantic region. Upon arrival, migrants provided the region with much-needed labor, but also faced challenges due to widespread discrimination and the decline of industrial employment. Still, many persevered and built a strong network of community resources within an increasingly diverse region.

Alyssa Ribeiro is an Assistant Professor of History at Allegheny College. Her research has examined relations between Puerto Rican and African American residents in postwar Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Photos document 200 years of Latino history in Philadelphia (WHYY, March 19, 2013)

- Scenes from Philly's Latino Barrio festival [photos] (WHYY, September 12, 2013)

- Celebrating two Latino luminaries from Philly on NYC stage (WHYY, March 14, 2014)

- 'Estamos Aqui' flocks into this Puerto Rican neighborhood in Philly (WHYY, May 4, 2024)

Links

- In the Heart of Gold (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- PhilaPlace: Concilio (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: El Centro de Oro – The Golden Block (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- In Kensington, Immigrants Spark a Philly Soccer Revival (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Cobertizos of Kensington (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- PhilaPlace: Congreso de Latinos Unidos headquarters and Casita (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Centro Musical: A Music Store with Family Values (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Puerto Rican Migration Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)

- Mapping Puerto Rico's Hurricane Migration With Mobile Phone Data (CityLab)