Restaurants

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

From colonial-era taverns to the celebrity chef establishments of the early twenty-first century, Greater Philadelphia’s restaurants illuminated the region’s socioeconomic, cultural, and culinary trends while also providing sustenance for millions, employing thousands, and in some cases emerging as historic and nostalgic treasures.

Taverns and public houses (“pubs”) represented the area’s earliest food-serving establishments; many operated in private residences, catered to diverse clienteles, and provided ample alcohol. The area’s oldest surviving taverns include the Broad Axe Tavern (est. 1681) in Ambler, Pennsylvania; the Barnsboro Tavern (est. 1720) in Sewell, New Jersey; and Jessop’s Tavern (est. 1724) in New Castle, Delaware. William Penn (1644-1718) noted in the 1680s that Philadelphia contained a handful of taverns with “a good meal to be had for sixpence,” but it was not until the 1750s that taverns began serving table d’hôte (“ordinary food”) with locally obtained produce, meats, and grains. Funded by subscriptions, Pennsylvania Journal editor William Bradford (1719-91) in 1754 opened the Old London Coffeehouse (Front and High Streets), which contained separate floors for drinking alcohol and coffee and minimal food offerings.

As Philadelphia developed into colonial America’s primary urban center, fancier restaurants appeared. The exclusive City Tavern (Second and Walnut Streets) opened in 1773 and gained a reputation for opulent banquets. Recalling dining there during the First Continental Congress, John Adams (1735-1826) praised the tavern’s “thousand delicacies” and fine wines. Hoping to appeal to non-elite customers, in 1780 Vincent Pelosi opened the Pennsylvania Coffeehouse (Front and High Streets) and later a second location in Camden, New Jersey. In 1791, James Oeller opened his eponymous hotel, Philadelphia’s first, at Sixth and Chestnut Streets. Oeller’s assembly room, decorated with French wallpaper and antique illustrations, challenged the City Tavern as Philadelphia’s finest banquet space. In addition to these establishments, Philadelphians satisfied their hunger by preparing meals at home or patronizing street vendors selling products ranging from fruits and vegetables to pepper pot soup and oysters. Oyster purveyors, centered on Philadelphia’s Dock Street, supplied vendors and restaurants alike. They proved so popular that discarded shells were used for ship ballast and street paving. Shad, plentiful in the Delaware River and later celebrated by local artist Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), was especially popular.

International Ingredients

In the early 1800s, Philadelphia became more cosmopolitan as its merchants traded with the Caribbean, China, and Europe, leaving the area awash in foreign foodstuffs. Philadelphia’s hotels, including the United States (Chestnut Street), the Merchants’ (38 N. Fourth Street), Mansion House (Third and Spruce Streets), and the La Pierre (Broad and Chestnut Streets) offered French cuisine and Parisian-style coffee. The Continental Hotel (Ninth and Chestnut), the city’s most opulent, contained a main dining room and “gentlemen’s café.” In the Washington Hotel’s kitchen (20 S. Sixth Street), co-owner Elizabeth Rubicam prepared what was considered the best terrapin (marsh turtle) dishes in the region.

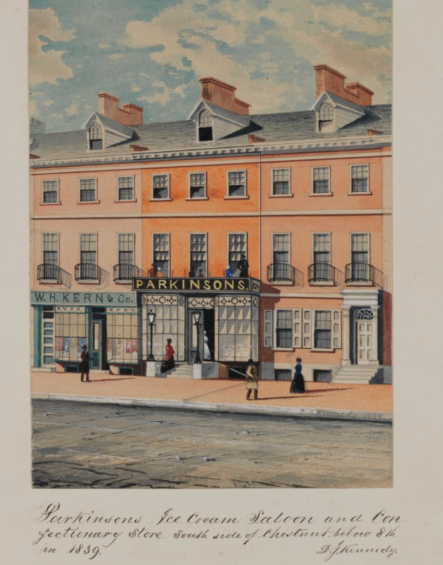

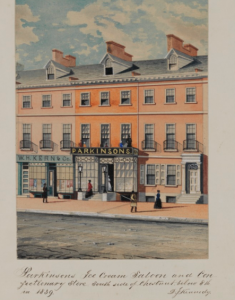

Confectioners and chefs also opened restaurants. James W. Parkinson, the son of a tavernkeeper, operated not only a famous restaurant at 180 Chestnut Street and produced Philadelphia’s most popular ice cream (Parkinson’s), but also in 1851 bested New York’s Delmonico’s restaurant in a seventeen-course cook-off dinner (later called the “thousand-dollar dinner”) that earned him a standing ovation. M. Latouche, a French chef once employed by the Russian minister in Washington, emerged as a popular restaurateur. His Market Street establishment, complete with an oyster cellar, offered quail, beef, mutton chops, and oyster pies. Prominent Philadelphians, such as bank president Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844), retained Latouche for private banquets.

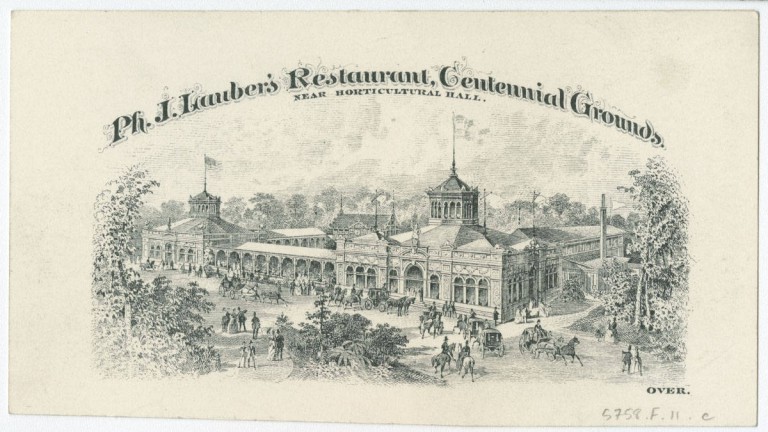

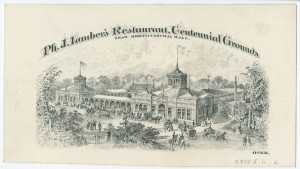

Following the Civil War, increases in transportation, immigration, and industrialization altered dining practices and restaurant offerings. When millions of visitors attended the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, they found not just the latest industrial and technological developments but also cuisine from around the globe. In addition to Brazilian, Japanese, Spanish, and Hawaiian delicacies, the Centennial featured Philadelphian Phillip J. Lauber’s (1830-81) German restaurant, able to accommodate 1,200 customers at once, which became the fair’s most successful largely due to the “Hamburg steak” (hamburger) on its menu. Though Philadelphians did not embrace the decadent “lobster palace” trend of the 1880s pioneered in New York City by Café Martin, the city’s finer establishments served dishes such as Lobster Thermidor and Lobster Newburgh.

Mirroring the region’s economic disparities as thousands of immigrants arrived during the Gilded Age, Philadelphia and the area’s larger cities (Wilmington, Camden, and Trenton) developed ethnic and working-class neighborhoods with tiny eateries serving Italian, Polish, German, and Irish food. In some cases, people operated restaurants out of their homes, catering to friends and neighbors. By 1900, Philadelphia contained a thriving Chinatown with “chop suey joints” along Race Street, east of Broad. Around the city, many former oyster stalls became full restaurants, including Snockey’s (Second Street and Washington Avenue.), Boothby’s (Thirteenth and Chestnut Streets), and Bookbinders (moved to Second and Walnut Streets in 1898). Bookbinders became one of Philadelphia’s most famous restaurants until its closing in 2009.

Department Store Dining Rooms

In the early twentieth century, department stores and “grand hotels” allowed diners higher degrees of luxury in their restaurant choices. Among Philadelphia’s Market Street department stores, Gimbels by 1902 contained a full-service restaurant as well as a deli and soda fountain/lunch counter. By 1912 Strawbridge’s boasted one of the finest restaurants in the city, but Wanamakers Grand Crystal Tea Room was Philadelphia’s largest; on average, the restaurant served 3,000 patrons per day and offered items such as caviar and sweetbreads. The majority of department store diners were middle- to upper-class women while lower- to middle-class men patronized lunch counters inside Broad Street Station and the Reading Terminal. Upper-class men dined at Green’s Restaurant (Eighth and Chestnut Streets), the New Bingham Café (Eleventh and Market Streets), and Boothby’s (Thirteenth and Chestnut Streets).

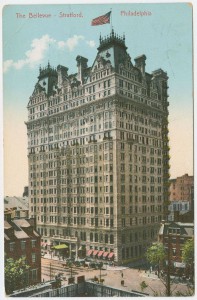

Perpetuating Gilded Age opulence, the region’s “grand hotels” offered the finest restaurants of the period. Establishments such as the Stenton, the Lafayette, the Walton, the Warwick, and the Bellevue-Stratford provided guests not only banquet-style meals but also richly decorated spaces in which to dine; the Walton’s Palm Room and Pierrot Roof Garden hosted lavish meals while the Bellevue-Stratford offered the South Garden Room (the place to be seen among the city’s elite), the Hunt Room (where power brokers lunched) and a separate Ladies’ Dining Room. North along Broad Street, the Lorraine Hotel’s Café Lorraine could accommodate three hundred people for dinner. Grand hotels also opened in 1913 in Wilmington (the Hotel DuPont) and in 1925 in Camden (the Walt Whitman). The Green Room in the Hotel DuPont stood as Delaware’s most refined dining establishment.

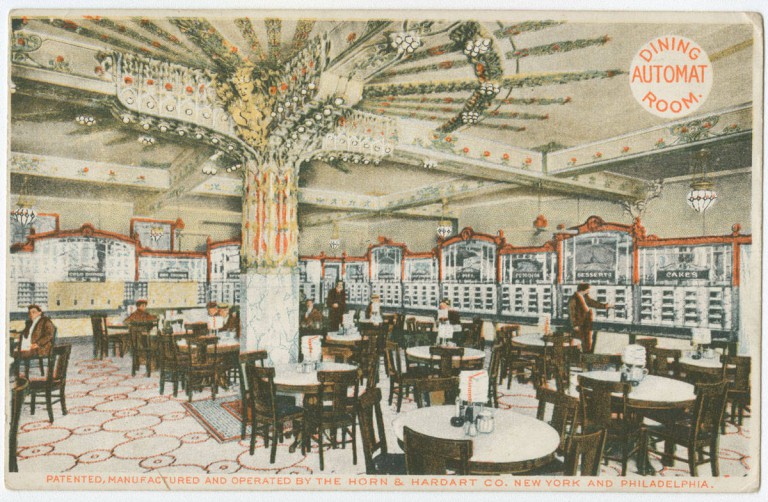

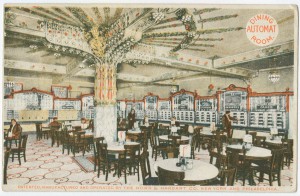

Independent restaurant operators also thrived. In 1915, Fritz Pflug opened the Arcadia restaurant in Penn Square’s Widener Building; by the 1930s, the renamed Arcadia International Restaurant and Club hosted the top musical acts of the time. In 1922, hoping to capture motorist traffic between Philadelphia and New York, Pflug opened Evergreen Farms on Roosevelt Boulevard, a “suburban café” advertised as “most beautiful restaurant in the country.” For those lacking the means or time to patronize department store or hotel restaurants, the region offered dairies, rathskellers, ice cream parlors, lunch wagons, cafeterias, automats, and “quick lunches” (luncheonettes). The first automat, opened in 1902 at 818 Chestnut Street by Joseph Horn (1861-1941) and Frank Hardart (1850-1918), set the standard for quick restaurant meals for people on the go. In the midst of the Great Depression, Pat Olivieri (1907-74) created the cheesesteak at his South Philadelphia hot dog stand in 1932, ultimately making that sandwich synonymous with the city. Small, family-owned Italian restaurants remained numerous in South Philadelphia and along Wilmington’s Union Street; Philadelphia’s Dante and Luigi’s (est.1899), Ralph’s (est.1900), and Wilmington’s Mrs. Robino’s (est.1940) all survived into the first decades of the twenty-first century.

Rise of the Diners

After World War II, increasingly propelled by cars and expressways, residents of the Philadelphia region patronized diners and drive-throughs. Although the diner first appeared in the 1870s in Rhode Island, Greater Philadelphia eventually contained dozens of the beloved institutions. Many of Philadelphia’s diners, including the Melrose, the South Street, the Oregon, the Broad Street, and the West Oak Lane, became neighborhood landmarks. Yet New Jersey, with key transportation routes between New York and Philadelphia as well as hundreds of suburban communities, contained more diners, per capita, than any other U.S. state. Famous South Jersey diners included the Deepwater (Carney’s Point), Olga’s (Marlton), the Club (Bellmawr), and Angelo’s (Glassboro). Chain restaurants also expanded in the postwar years. Companies such as Stouffer’s, Savarin, Ponderosa, Horn and Hardart, Gino’s Hamburgers, and McDonald’s opened urban and suburban locations in the 1950s and 1960s. Private dining clubs, including the Vesper, the Bellevue Court, Union League, Embassy, Saxony East, and Quo Vadis continued to thrive in central Philadelphia. “Chop houses” served as the forerunner of modern steakhouses; in the 1960s and 1970s, Philadelphia’s Frankie Bradley’s, Arthur’s, Leibowitz’s, and Mitchell’s, as well as Wilmington’s Constantino’s House of Beef, appealed to those with a fondness for beef.

Philadelphia in the early 1970s underwent its first “restaurant renaissance.” Prior to that decade, many downtown workers and residents felt the city lacked a reputable dining-out scene; some joined one of Philadelphia’s many supper clubs to ensure a decent meal. While many new eateries in the 1970s, such as Alexander’s, Astral Plane, Broadway Eddie’s, Friday Saturday Sunday, Gilded Cage, Lickety Split, Knave of Hearts, and White Dog Café were casual and experimental, young, enterprising chefs such as Steve Poses (b.1947), Peter Frederick Von Starck (1942-84), and Georges Perrier (b.1944) introduced French nouvelle cuisine to local Baby Boomers eager to expand their palates. Several French restaurants appeared in the 1970s, including Le Pavillon, Lautrec, Les Amis, La Panetiere, Déjà vu, Frog, and the Bellevue-Stratford’s Versailles. Yet no other French restaurant in Greater Philadelphia received more accolades than Perrier’s Le Bec-Fin, which opened in 1970 on Spruce Street and later moved to larger quarters on Walnut Street. For several years Le Bec-Fin received the coveted Michelin three-star award and was considered among the finest restaurants in the United States. Besides French, northern Italian cuisine also defined the renaissance; following Gaetano’s (Seventh and Walnut) were the Monte Carlo Room (Second and South) and the Saloon (Seventh and Fitzwater).

Festival Marketplaces

As Philadelphia competed with suburban shopping malls and their food courts in the 1970s, the “festival marketplace” arrived with the Louis Sauer (b.1928)-designed New Market, a shopping-dining complex adjacent to Society Hill’s Headhouse Square. New Market’s restaurants ranged from the Dickens Inn (English pub fare) and Café Lisboa (Spanish-Portuguese) to Focolare (Italian) and the Rusty Scupper (seafood). In 1973, restaurateur Neil Stein (b.1941) opened the Fish Market at Eighteenth and Sansom Streets in Philadelphia. By the late 1990s, Stein’s restaurant empire included Marabella’s, Avenue B, the Striped Bass, and the city’s most popular sidewalk café, Rouge.

After Greater Philadelphia experienced capital flight, deindustrialization, and suburbanization through the 1980s, restaurants from the 1990s into the early decades of the twenty-first century played a major role in the region’s economy and signaled a second renaissance. New waves of immigration from Asia and Latin America remade the area’s restaurant scene by opening pho and dumpling houses, Korean BBQs, sushi bars, and taquerias in neighborhoods from East Passyunk Crossing to Cheltenham. By 1998, food service positions comprised nearly 12 percent of all employment in Philadelphia; in 2015, Pennsylvania had the country’s sixth-largest restaurant workforce. Towns in South Jersey, such as Collingswood and Haddonfield, also relied on restaurant growth for their economic vitality.

While mainstays such as Bookbinders and Le Bec-Fin lasted into the 2000s, a new generation of talented chefs challenged them by opening popular restaurants and catering to millennial tastes. They included Jose Garces (b.1971) (Amada, Tinto, Distrito, Rosa Blanca), Marc Vetri (b.1968) (Osteria, Amis, Vetri), Michael Solomonov (b.1978) (Zahav, Federal Donuts, Percy Street BBQ), and Chris Scarduzio (b.1965) (Brasserie Perrier, Table 31, Mia). By mid-decade, James Beard Foundation finalists and Top Chef contestants, including Marcie Turney (Lolita, Barbuzzo), Jennifer Carroll (b.1982) (10 Arts), Garces, and Masaharu Morimoto (b.1955) (Morimoto), further cemented Philadelphia’s national dining out profile with their acclaimed eateries.

Popularity of BYOBs

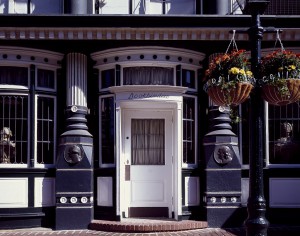

With liquor licensing prohibitively expensive in Pennsylvania and New Jersey since Prohibition’s repeal, BYOBs thrived in both states; though Philadelphia contained more per capita than any other U.S. city, many towns in New Jersey, including Collingswood, Cherry Hill, and Haddonfield had thriving BYOB scenes. After 1995, with the debut of his revamped Continental diner in Old City, no other restaurateur in Greater Philadelphia was more recognized than Stephen Starr (b.1956). Using specific themes (French bistro, British pub) and echoing existing restaurants (New York’s Odeon, Hollywood’s Roscoe’s), Starr created popular eateries throughout Philadelphia (Buddakan, Pod, Talula’s Garden) and South Jersey (outposts of Continental and Buddakan in Atlantic City) that enlivened the region’s dining out scene. By 2012, his Rittenhouse Square bistro Parc was the highest-grossing among his more than twenty restaurants in four states.

Through centuries of urban growth, immigration, economic and cultural exchange, and changing culinary trends, the restaurants of Greater Philadelphia provided not only nourishment, employment, and entertainment but also allowed residents and visitors alike to experience and identify with the region.

Stephen Nepa teaches history and American studies at Temple University, Rowan University, and Moore College of Art and Design. A contributor to numerous books and journals, he also appears in the documentary series Philadelphia: The Great Experiment and The Urban Trinity: The Story of Catholic Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- America's oldest Italian restaurant is right here in Philadelphia (WHYY, May 27, 2012)

- Once internationally acclaimed, Le Bec-Fin closes doors for good (WHYY, June 14, 2013)

- Roxborough native Justin Bogle returns to Philadelphia to head up Avance (WHYY, January 30, 2014)

- The Olde Bar is the new edition of iconic Bookbinder's (WHYY, January 6, 2015)

- Last call for Snockey's after more than a century (WHYY, November 27, 2015)

- Dishing DNC: Philly’s food scene through the eyes of our elected officials (WHYY, July 5, 2016)

- Burned by papal visit, Philly restaurateurs warming up to prospect of DNC (WHYY, July 11, 2016)

Links

- London Coffee House Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- PhilaPlace: The City Tavern - A Taste of Philadelphia History (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Oellers Hotel - Definitely Philadelphia Original (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Hungry for Authenticity at Second and Walnut (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Staying in Philadelphia: The Hotel Stenton and Hotel Walton (PhillyHistory Blog)

- A Man Full of Trouble: Philadelphia’s Last Surviving Colonial Tavern (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Rebooting Bookie’s: Garces Group Awakens The Spirit Of An Old Original Legend (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Rise and Fall of Philadelphia's Diners (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The food tree: Top Philadelphia restaurateurs nurture next generation of fine-dining talent (Philadelphia Daily News)