Puerto Ricans and Puerto Rico

Essay

The centuries-long relationship between the Philadelphia region and Puerto Rico unfolded in four interrelated areas: economic links, political channels, personal networks, and cultural exchange. Several dynamics shaped those connections over time. Colonialism, first under Spain and later the United States, set the broad context for trade relations and government policies. Individual reactions to those policies in turn drove the movement of people, capital, and ideas. Over time, advances in transportation and communication technologies increased the frequency and volume of connections across roughly sixteen hundred miles of ocean.

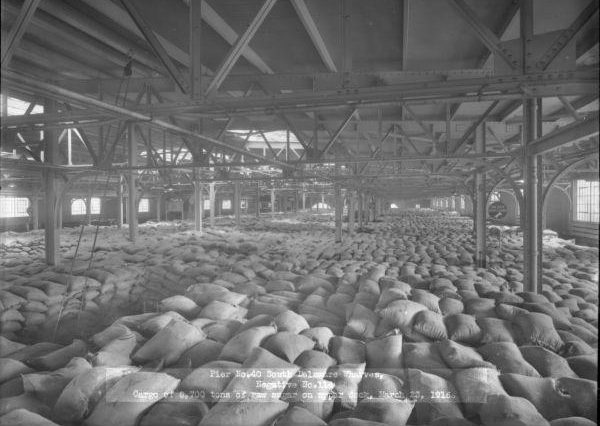

Early links between the two geographic areas were part of the broader Atlantic exchange of humans and commodities. In the early 1700s, Philadelphia traders complained of raids by Puerto Rican privateers, who sought to steal their lucrative cargo of slaves. During the wars between Atlantic powers in the early 1800s, the ports of San Juan and Philadelphia facilitated transshipment of goods and relayed communications across the ocean. The Red D shipping line of merchant John Dallett (d. 1862) set sail between Philadelphia and Caracas, Venezuela, in 1820; its vessels commonly docked at Havana, Cuba, or San Juan, Puerto Rico, as well. Much of the island’s early trade with Baltimore and Philadelphia was controlled by George Latimer, son of a prominent Philadelphia family, who served briefly as the American consul in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico, in the 1830s. Sugar and tobacco were especially important aspects of trade, as Philadelphia housed numerous sugar refineries and cigar factories. As sugar consumption increased, Philadelphia’s imported tonnage was second only to New York’s. The local tobacco processing industry, which first arose to handle Pennsylvania-grown crops, began to incorporate smaller quantities of Caribbean tobacco in the early nineteenth century. The parallel migration of cigar workers from Puerto Rico and Cuba to Philadelphia allowed local concerns to market “Havana-filled” and “Cuban-made” cigars. Mid-Atlantic flour, which resisted spoilage in tropical climates, accompanied other staples and manufactured goods on return trips to the Caribbean.

Spanish-speakers in the Philadelphia region were politically active, pressing for both Cuban and Puerto Rican independence from Spain. In 1822, a small armed force left Philadelphia intent on invading Puerto Rico, but its plans were thwarted by capture. Later in the century, local expatriates joined organizations like the Republican Society for Cuba and Puerto Rico and the Partido Revolucionario Cubano. Meanwhile in the Caribbean, armed insurrection against Spanish rule quickly gained the endorsement of the U.S. government.

American expansionism, public outcry over the indignities of Spanish rule, and the explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor led to the Spanish-American War in 1898. Material and men from the Philadelphia region backed the U.S. campaign. Cramp & Sons Ship and Engine Building Company supplied naval vessels, many of which bore armor and armaments from other Pennsylvania companies such as Bethlehem Steel and Midvale Steel. Meanwhile, the Pennsylvania National Guard saw only limited action after being deployed to Puerto Rico, despite being among the best prepared state militias. That did not discourage Philadelphia from hosting an elaborate three-day-long Peace Jubilee in October 1898 to honor the troops and American victory. Puerto Rico remained under U.S. military rule until 1900.

A Hope for Profits

Companies based in the Philadelphia region hoped to profit from development of the Caribbean islands. Pennsylvania businesses supplied equipment and management for railroad and pier construction in Puerto Rico. Similarly, the Puerto Rico Company, a New Jersey company headquartered in Philadelphia, held franchises for lighting, ice, and brick plants in Ponce, Puerto Rico. Caribbean investments also promoted more philanthropic endeavors. When a cyclone devastated Puerto Rico’s food supplies in 1900, Philadelphia donors quickly filled an entire ship’s worth of food aid. Baltimore soon followed suit.

As the United States gained influence over Cuba and control of Puerto Rico, scathing critiques of American imperialism circulated through Spanish-speaking communities in the Philadelphia region. While island exports had long been sold to the United States market, American political control severely limited Puerto Rico’s ability to export to other nations. Displacement wrought by the swift consolidation of land ownership created the appearance of surplus population on the island. Laborers recognized their increasing subjugation to the American capitalist system. In the years surrounding World War I, some Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia joined the Industrial Workers of the World and helped to distribute anarchist newspapers while maintaining close contact with island allies.

In the early twentieth century, Quakers from the mid-Atlantic region worked to liberalize U.S. policy toward Puerto Rico, though their efforts were limited by widespread assumptions about racial hierarchies. After the Jones Act of 1917 granted them U.S. citizenship, Puerto Ricans could migrate to the mainland United States without threat of deportation. But this citizenship carried severely limited political power, as island affairs remained subject to the oversight of an appointed governor and the United States Congress. Such control derived, at least in part, from recognition that Puerto Rico’s geographic position, in particular its proximity to the Panama Canal, made it a valuable military asset for the United States.

During the early twentieth century, Puerto Rico’s image as an idyllic tropical island drew a limited number of tourists from the Philadelphia region. Although San Juan was less accessible by ship than other Caribbean ports such as Havana and Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, demand for the very limited passenger service to Puerto Rico was high and usually required advance reservations. At the same time, the racial mixing common among Puerto Rican passengers on second-class ships offended the segregationist ideals of some white passengers from the mid-Atlantic.

Growing Bonds

The throes of the Great Depression and the contingencies of World War II further consolidated links between the mid-Atlantic and Puerto Rico. Labor organizations attempted to respond to systemic economic crisis through coordinated campaigns. Striking cigar makers, for instance, simultaneously halted production in Camden, New York City, Tampa, and Puerto Rico in 1933. Soon after, military demands funneled the flow of resources. Puerto Rico remained a strategic location, and Philadelphia-based McCloskey and Company won a $4.7 million contract to construct portions of the air base at Punta Borinquen during World War II. Meanwhile, the War Manpower Commission coordinated the movement of laborers to the mid-Atlantic in order to aid with defense production; about five hundred Puerto Ricans went to work at Camden’s Campbell Soup Company. They joined other Puerto Rican migrants drawn by agricultural employment in the region.

From the late 1940s, two major dynamics impacted the Philadelphia region’s relationship with Puerto Rico. First was an assertive economic development policy called Operación Manos a la Obra (Operation Bootstrap) that sought to industrialize the previously agricultural island. A second, related development was a concerted effort to promote labor migration off the island to solve the perceived problem of overpopulation.

Alongside the Puerto Rican government’s efforts to promote labor migration, labor recruiters based in the Philadelphia region built personal relationships with island residents. In particular, Samuel J. Friedman, who had been born in Puerto Rico, played a prominent role in steering Puerto Rican workers to South Jersey farms and establishing a Migration Division office in the region. By the late 1950s, Puerto Rican labor migrants predominated in the mushroom growing industry surrounding Kennett Square. As Puerto Rican populations increased, first churches, then other local institutions, and eventually city governments began offering accommodations for Spanish speakers.

The advent of regular air travel between Philadelphia and San Juan in the late 1950s greatly increased population flows back and forth. Many passengers were Puerto Rican labor migrants, but Puerto Rican officials also pleaded for increased air service in order to accommodate more tourists. By the 1940s, Puerto Rico had become a vacation destination for some of Philadelphia’s Black middle class, who built social relationships with their island peers. Between 1958 and 1967, Nancy Middens (1913-89) wrote a column for the Philadelphia Tribune called “Under Two Flags,” which sought to inform readers about both the island and Puerto Rican migrants to Philadelphia. In 1967, Black attorney and politician Charles Bowser (1935-2014) represented Philadelphia on a goodwill trip to Puerto Rico. The Reverend Leon Sullivan (1922-2001), a civil rights leader and proponent of economic uplift, also traveled to the island and established a Puerto Rican branch of the Opportunities Industrialization Center.

Sports provided one avenue of cultural exchange—especially baseball and boxing. The Philadelphia Athletics, the Philadelphia Phillies, and Camden’s minor league baseball team all traveled to play in the Caribbean in the early twentieth century. Higher-paying island teams lured players such as Gene Benson (1913-99) away from the Negro League’s Philadelphia Stars. In the following decades, the Philadelphia Phillies regularly sent coaching staff and players including Grant Jackson (b. 1942) and Mike Schmidt (b. 1949) to participate in the Puerto Rico Winter League. Numerous Puerto Rican-born players such as Willie Montañez (b. 1948) eventually found places on the rosters of the Philadelphia Athletics or the Philadelphia Phillies. Meanwhile, boxing fans in the mid-Atlantic followed the successful careers of numerous Puerto Rican fighters.

Promotion of Cultural Awareness

Events, exhibitions, television, and publications also sought to increase cultural exchange and awareness. Puerto Rican government officials and musicians regularly traveled to appear at events like Philadelphia’s North City Festival and Camden’s Saint John the Baptist Parade. In the early 1970s, North Philadelphia activist Maria Lina Bonet (1924-97) convinced Pan American Airlines to transport displays and artifacts from the island free of charge in order to stage a large exhibit on Puerto Rican life and art in Center City. Similarly, the Please Touch Museum mounted a “Salute to Puerto Rico” in 1984. These events dovetailed with sustained cultural programs by organizations like Taller Puertorriqueño and neighborhood festivals. Beginning in 1970, WPVI-TV broadcast a weekly half-hour show titled “Puerto Rican Panorama” for more than twenty years. During the 1980s and 1990s, Community Focus, a bilingual weekly newspaper, ran regular features on Puerto Rican history and politics.

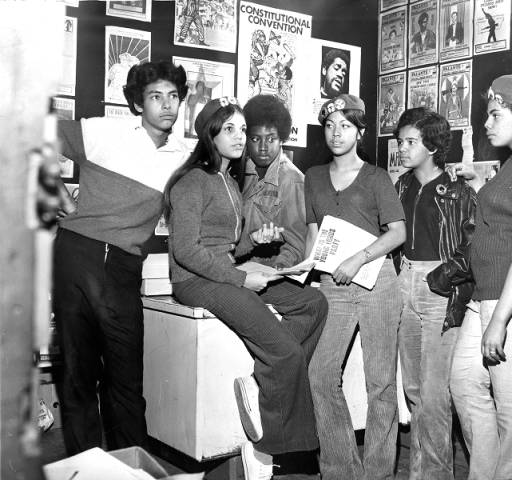

Growing Puerto Rican nationalism impacted the Philadelphia region, where it intersected with civil rights activism, Black Power advocacy, and opposition to the Vietnam War. Leftist Puerto Rican groups drew direct connections between the island’s colonial status and the depressed economic condition of mainland barrio residents, but sometimes struggled to balance those causes. When Philadelphia’s chapter of the Young Lords occupied a North Philadelphia church in 1970 to offer legal aid and fight local drug trafficking, their prominent display of the Puerto Rican flag disturbed some of the Black congregation, while others were eager to collaborate with the Lords on community programs. Across the river, flags and signs reading “Puerto Rico Libre!” lined the streets during an uprising following an altercation between a Puerto Rican motorist and Camden police in 1971. The Movimiento Pro Independencia (MPI), which evolved into the mainland division of the Puerto Rican Socialist Party (PSP), attracted members in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Puerto Rican independence figured prominently in the “Bicentennial without Colonies,” staged by the PSP and allied organizations in Fairmount Park in 1976. The parade and demonstration drew approximately forty thousand participants, despite the Rizzo administration’s efforts to discourage the event. Beginning in the late 1970s, Philadelphia’s Puerto Rican Alliance, under the leadership of figures including Juan Ramos (b. 1951), Angel Ortiz (b. 1941), and Ralph Acosta (b. 1934), carried on the mantle of addressing both city and island issues.

Concern over the impact of the American naval base on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques also resonated on the mainland. Decades of heavy weapons testing contaminated the environment, endangered public heath, and threatened the livelihood of local fishermen. The navy’s activities recurrently drew protests from Puerto Rican populations and Philadelphia members of the Vieques Support Network. Even after the Navy withdrew in 2003, serious environmental damage and health risks remained.

Economic connections between Philadelphia-area companies and Puerto Rico grew more complex toward the end of the twentieth century. As manufacturing concerns decreased their presence in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, they took advantage of generous corporate tax incentives and lower labor costs available in Puerto Rico. In the 1960s and 1970s companies including metal products fabricator Perry Equipment, toy producer De Luxe Reading Corporation, and garment maker Rosenau Brothers started production on the island. First Pennsylvania Bank acquired financial interests in Puerto Rico as part of an aggressive growth strategy. The movement of pharmaceutical and medical supply companies such as Wyeth Labs and National Label Company followed in the 1980s and 1990s. With waves of business consolidation, conglomerates including Campbell Soup Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Alco Standard, and Sun Oil operated facilities in Puerto Rico as well as the mid-Atlantic region.

Migration Persists

Migration from Puerto Rico to the Philadelphia region continued throughout the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. For many families, movement between the island and mainland was bidirectional as economic and personal circumstances changed. Economic turmoil on the island brought increased migration to Philadelphia as it grew to house the second-largest mainland concentration of Puerto Ricans. In July 2016, the U.S. Congress enacted the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) to address the island’s growing debt crisis and the possibility of lawsuits from creditors. Puerto Rican populations in the mid-Atlantic joined their Caribbean counterparts in criticizing the power granted to an unelected financial oversight board.

Over several centuries, ties between the Philadelphia region and Puerto Rico formed and evolved within colonial structures. Economic connections moved from the trade of agricultural commodities to infrastructure development and capital-intensive production facilities. The nature of those economic links in turn encouraged flows of labor migration to the mainland and capital migration to the island. Political advocacy, cultural events, and tourism added complexity to regional relationships. Overall, the mid-Atlantic’s myriad connections to Puerto Rico represent a microcosm of broader processes of globalization.

Alyssa Ribeiro is an Assistant Professor of History at Allegheny College. Her research has examined relations between Puerto Rican and African American residents in postwar Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Neighbors: Exploring 200 Years of Puerto Rican History in Philadelphia (Historical Society of Pennsylvania / Taller Puertorriqueño)

- The Changing of the Guard: Puerto Rico in 1898 (Library of Congress)

- William Cramp & Sons Ship and Engine Building Company (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- The Philadelphia Peace Jubilee of 1898 (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- Operation Bootstrap (1947) (Puerto Rico Encyclopedia)

- Philadelphia’s Puerto Rican Alliance (El Concilio)

- Taller Puertorriqueño

- Puerto Rican Panorama