Single Tax Movement

By Christopher England | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

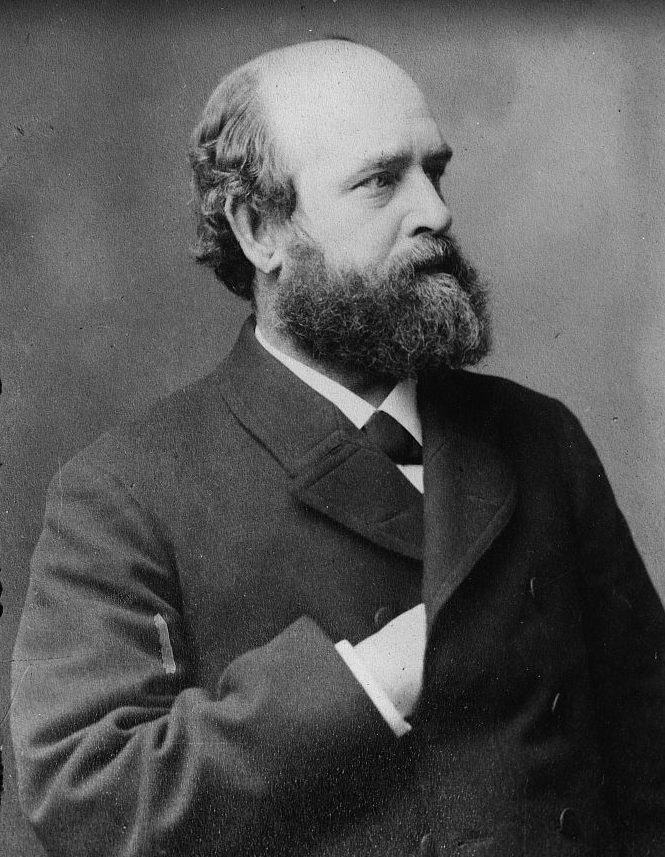

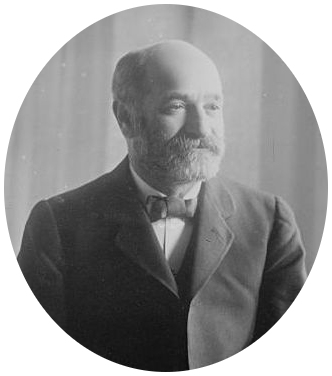

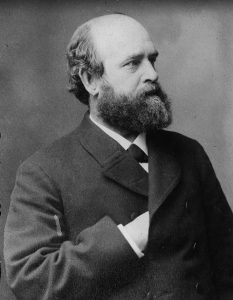

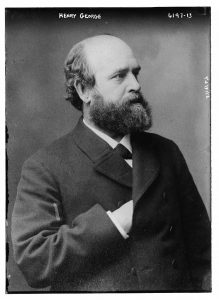

During the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, Philadelphia helped give birth to the single tax movement, one of the country’s more influential, if less well-remembered, reform movements. The idea of a “single tax” on the unimproved value of land, rather than on productive activities, was popularized by Henry George (1839-97), a native of Philadelphia. The city was also home—at least periodically—to one of the movement’s most prominent twentieth-century leaders, Joseph Fels (1853-1914). Thus, the Philadelphia region became a major epicenter for a movement that maintained that the value of land should benefit the whole community, rather than serve as a source of wealth for private individuals. By the 1920s, the region was home to a prominent communal single-tax experiment and to substantive tax reform inspired by George’s ideas.

The son of a Democratic Party activist, George was influenced in his youth by the city’s vibrant social movements, particularly abolitionism and the Working Men’s Party. The first of these inspired in George a belief in the free market, whereas the second instilled the idea that access to land was important for truly free competition. Later in his life, George developed close personal relationships with some notable veterans of both movements. However, George did not fully formulate his philosophy until after he moved to San Francisco in 1858. There he gradually concluded that high urban rents were consuming all the gains of industrialization. He came to believe that increasing population and demand for natural resources caused the value of the world’s finite stock of land to increase in value, skewing wealth toward the elite, even when owners did nothing but idly hold their property.

In 1879, George published Progress and Poverty, in which he argued for what his followers later called the “single tax.” All government revenue, he posited, should be derived from a tax equivalent to the full rental value of land. George, an advocate of free trade, was eager to end the federal tariff system, but also to fund social welfare programs. Land values were defined as the value of natural resources and premiums for urban locations. Buildings were not to be taxed because they were the product of labor and contributed to the progress of the community. Land, on the other hand, was created by God and belonged to all in common. George believed that industry should be free from taxation and regulation and that the confiscation of land rents would be sufficient to fund programs such as free public transportation and higher education. George’s unique combination of classical liberalism and socialism won a wide hearing. He campaigned twice for mayor of New York City, even outpolling his Republican opponent, Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), in a three-way race during the campaign of 1886. By the time of his death in 1897, about five million copies of George’s books had been distributed throughout the world, making him one of the most widely read American writers of the nineteenth century.

During the election of 1896, Georgists formed the Single Tax Party to wage a concerted campaign for control of Delaware’s state government. Single taxers believed that because Delaware was such a small state a nationally organized campaign would have disproportionate influence there. However, splintering voters from the major parties during that year’s hotly contested presidential election proved impossible; George himself largely stayed away from Delaware to cover the campaign of William Jennings Bryan (1860-1925). However, Delaware’s Single Tax Party connected local Georgists who would be active in the state during later years. In 1900, Georgists created a village outside of Wilmington, Delaware, as an experiment in the single tax. They founded this village, Arden, as a private corporation that owned the land and leased it to residents. The corporation used the revenue from leasing land to fund community projects and cover the residents’ taxes, largely realizing the goal of paying all taxes in the form of land rent. Arden not only survived the twentieth century with its system of revenue, but grew, annexing adjacent towns.

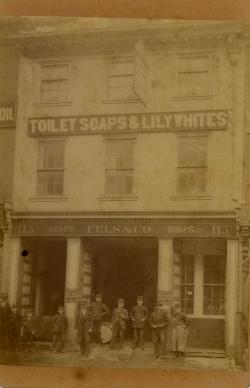

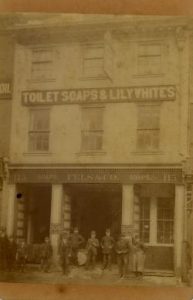

Though George never returned to Philadelphia, one of his most prominent followers, Joseph Fels, resided in the city periodically. Fels made a fortune marketing Fels-Naptha soap, one of the most commercially successful detergents of the era, and used his wealth to propagate both Zionism and the single tax. Fels helped form the Philadelphia Vacant Lots Cultivation Association in 1897. To demonstrate how the poor could help themselves if land was not held idle for speculation, this organization took abandoned lots in the city and lent them out for working-class families to farm. In 1909, Fels donated tens of thousands of dollars to create the Joseph Fels Fund, which spread Georgist propaganda across the globe and sponsored single-tax political campaigns. In the United States, it campaigned to have referendum processes established in several states, and then used the referendum to try, unsuccessfully, to enact the single tax.

Georgists obtained one of their largest legislative victories in Pennsylvania. They pushed for property tax reform following a study by J. T. Holdsworth, the dean of the School of Economics at the University of Pittsburgh, that demonstrated that the city suffered from unusually high rents. Georgists attributed the city’s high rents to a property tax system that underassessed land. In 1913, the state legislature enacted a law that enabled Pittsburgh and Scranton to impose a greater tax burden on land than improvements. This “split-rate” or “two-rate” tax did not remove taxes on buildings, but it did cut them in half, shifting the burden onto land values. By the latter half of the twentieth century, supporters of land value taxation cited Pittsburgh, which maintained relative prosperity during deindustrialization, as one of the chief examples of the benefits of land value taxation. In subsequent years, Pennsylvania’s state legislature expanded the law to allow other municipalities to shift the property tax burden onto land at progressively higher rates. Other cities later adopted the system, including Allentown and Harrisburg.

As American politics took a conservative turn in the 1920s, mass support for the single tax waned, although, throughout the world, taxes based on George’s plan remained in effect. The single tax movement retained some adherents throughout the twentieth century. The twenty-first century experienced an uptick in interest in land value taxation, primarily because rising urban rents resurrected concerns about real estate’s effect on the distribution of wealth. Philadelphia continued its important role in the movement, in part because it was George’s birthplace and in part because Pennsylvania offered the premier examples of land value taxation in the United States.

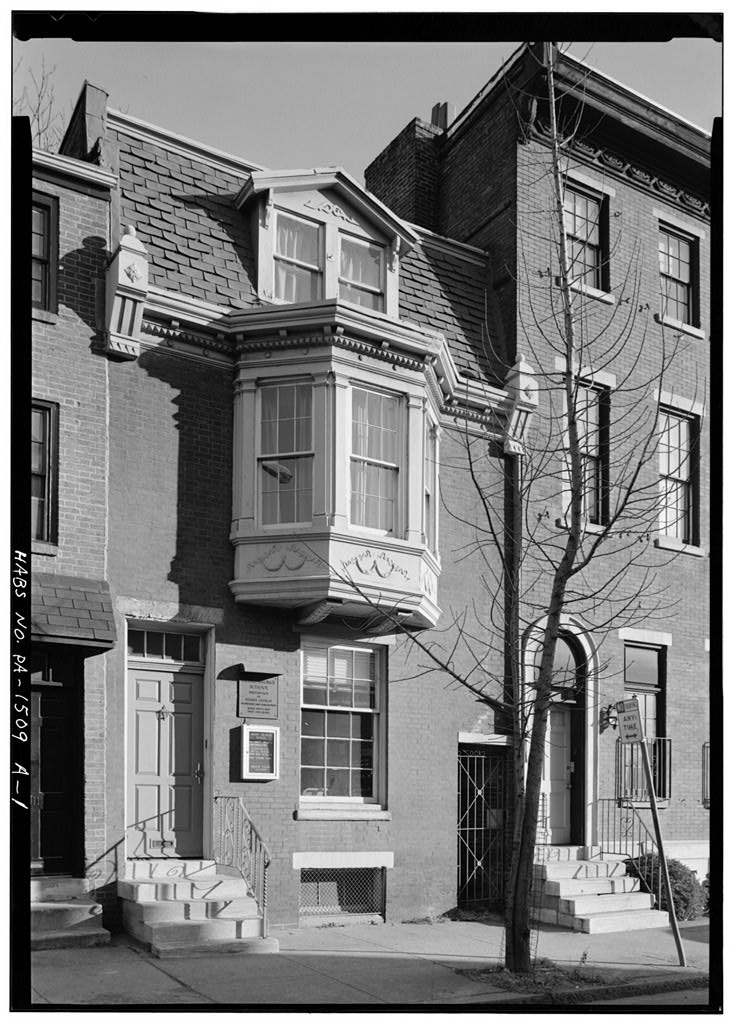

In 2013, the Henry George School of Social Science began operating Henry George’s Birthplace in Philadelphia as a museum and archive. The city’s unique history with the single tax has survived the test of time, becoming an integral part of Philadelphia’s heritage.

Christopher England has taught U.S. history at Georgetown University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He received his Ph.D. from Georgetown University, where he wrote his dissertation on the single tax movement. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University