Smith’s and Windmill Islands

Essay

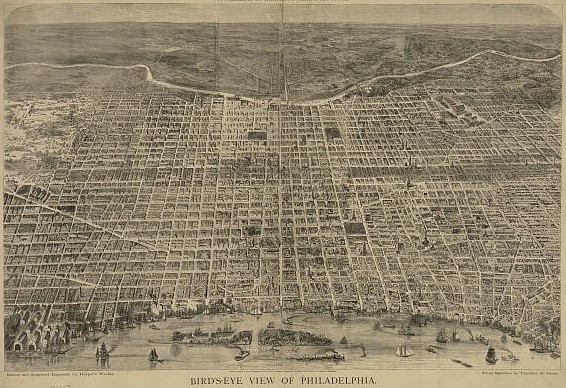

Once a prominent feature of the Delaware River between Philadelphia and Camden, Smith’s and Windmill Islands were shifting signifiers of the recreational, commercial, and financial development of the region. Originally one island, then segmented by a canal in 1838, the islands attracted early but unsuccessful proposals for bridges between Camden and Philadelphia. Although they served as a summer resort for the working classes for much of the nineteenth century, the islands became viewed as an impediment to the growth of the harbor and expansion of commerce. Between 1893 and 1897, dredging removed them.

The presence of a land formation in the Delaware River was noted by Thomas Holme (1624-95), the first surveyor general of Pennsylvania and designer of Philadelphia’s street plan, who observed “muddy mounds” opposite the city. Over the years, sediment, sand, and silt from the river accumulated on these shoals to form a single, twenty-five acre island. The hull of a ship, discovered later by dredgers removing the islands, may have contributed to the accumulation of sediment and debris and the formation of the island.

In 1746, John Harding (1700-47), a miller, erected a wharf and a windmill on the island, thus giving it its first popular name: Windmill Island. For several years, farmers brought grain to the mill at low tide by crossing over the sandbar that had formed between Cooper’s Ferry (the future site of Camden, New Jersey) and the north end of the island.

Split Between Two States

During the late eighteenth century, the island was also the execution site of several criminals convicted of murder or piracy. After the Revolution, Pennsylvania and New Jersey signed a treaty that divided the islands in the Delaware River between them. Pennsylvania took ownership of Windmill, while New Jersey controlled Petty Island, two miles to the north. In 1791, the Pennsylvania Assembly authorized selling several islands in the Delaware River, including Windmill, thus making tracts of land on the island available for sale to businesses and individuals.

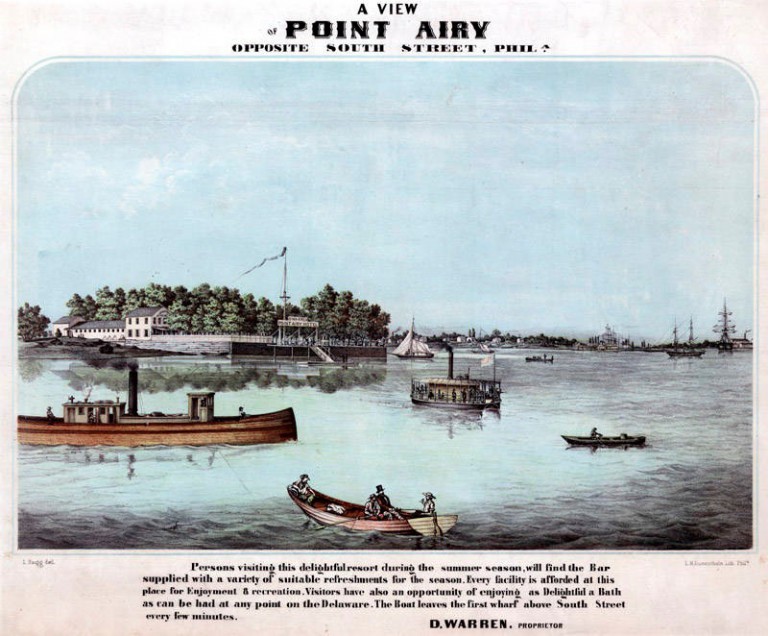

As early as the 1820s, Windmill Island became a site of leisure and recreation. With its willow and maple trees, it offered a cool respite from the summer heat of the city. By 1826, it even featured “floating baths” similar to those that became popular at the Battery in New York later in the century. From the 1840s through the 1860s, the island became a widely publicized viewing point and starting line for yearly summer regattas on the river.

The island’s position between Philadelphia and the developing site of Camden created an obstruction for ferry crossings but inspired proposals for bridges. In 1819, politicians discussed building a bridge linking Windmill Island to Camden. The previous year, Edward Sharp (1769-1834), developer of a ninety-eight-acre “Camden Village” addition to Camden, purchased seven-tenths of Windmill Island with the expectation that a bridge would be built from his properties to the island. Despite support from the New Jersey legislature, the bridge was never built, primarily because of insufficient funding. The plan also met resistance from boat captains and pilots, whose livelihood depended on water transit. In 1868, Thomas Say Speakman (1817-97), a civil engineer and native Philadelphian living in Camden, devised a plan for a double-draw, stone suspension bridge connecting Camden with Philadelphia via Windmill Island. Despite resistance by the Philadelphia City Council and initially by Philadelphia port wardens, the U.S. Congress endorsed the $2 million project so long as the bridge would not “obstruct, impair, or injuriously modify the navigation of the river.” The bridge was never built, however. The Philadelphia and Camden Bridge Company, which was responsible for implementing the plan, did not meet the timetable authorized by Congress. Consequently, the company forfeited the right to construct the bridge in 1876.

Impediment to Navigation

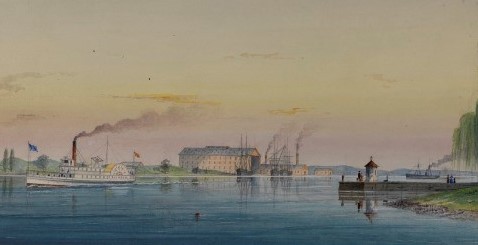

With ferries as the primary means of crossing between South Jersey and Philadelphia, the island became viewed as an impediment to navigation. For this reason, a 130-foot-wide canal created in 1838 split the island in two and allowed ferries between Camden and Philadelphia to sail directly between the two cities. The smaller, eight-acre northern island was named after Captain John Smith, who lived on the island with his family. The larger, seventeen-acre southern island retained the name “Windmill.” Not everyone recognized this distinction. For at least ten years after the canal was built, newspapers often referred to real estate on the northern island as being located on “Windmill, or Smith’s Island.” Later in the century, many called both islands “Smith’s Island.”

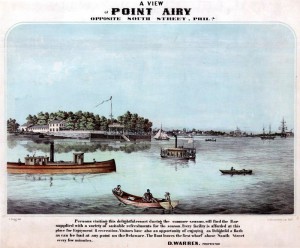

Windmill Island eventually saw the building of eight structures, including a coal depot and a lead works. It was also considered as a possible site for storing oil. David Warren (1800-?) operated the Point Airy Hotel and dock on its southern tip. A portion of the island also became a health resort for children. In 1877, the Sanitarium Association of Philadelphia transported children and their mothers to the island from hot, congested Philadelphia neighborhoods to enjoy recreation and free bowls of soup. Called “Soupy Island,” this summer resort moved in 1886 to Red Bank in Gloucester County, New Jersey (where it became the Sanitarium Playground of New Jersey and continued to offer summertime programs for children in the twenty-first century).

Smith’s Island, meanwhile, developed a reputation as a refuge for the “idle and dissolute.” Philadelphia entrepreneur and politician Jacob E. Ridgway (1824-1909) sought to change this when he purchased Smith’s Island in 1879 for a reported $55,000. The next year he renamed it “Ridgway Park,” which he envisioned as an inexpensive, healthful, and pleasant resort for the “respectable masses.” Herman J. Schwarzmann (1846-91), an engineer for the Fairmount Park Commission and architect of buildings for the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, helped reshape the island’s gravel walkways and rebuild the structures. A dancing pavilion was converted into a roller-skating rink, and a rundown saloon became a hotel. Two large, separate baths—for men and for women—could hold hundreds of swimmers. The park featured a bowling alley, hot-air balloon rides, tightrope-walkers, musical concerts, and a beer garden. Ridgway hoped his resort would ultimately become the Coney Island of Philadelphia. In time, rowdy fights and drunken scuffles became common, and the park was cited for prostitution. After Pennsylvania enacted more stringent “high license” liquor laws in 1887, sales of liquor on the island became illegal, and the resort lost much of its appeal for men from the city.

Dramatic growth of commerce on the Philadelphia waterfront eventually prompted the Board of Harbor Commissioners, the Board of Trade, and the Pennsylvania Railroad to call for removing the islands from the river so that the port might better compete with New York. If Smith’s and Windmill Islands could be eliminated, warehouse piers on the Delaware could be lengthened from 150 to as much as 500 feet, and the shipping channel could be dredged to the depth and width necessary to accommodate larger-hull, cargo-filled ships.

Throughout the 1880s, city, state, and federal governments discussed the financial, legal, and logistical measures necessary to remove Smith’s and Windmill Islands. In 1891, the Army Corps of Engineers contracted with American Dredging, a Philadelphia company, to do the work, and within two years, fourteen dredging machines began the process. Dredged material was deposited on League Island and in its back channel in South Philadelphia. Some also went to Petty Island. By 1897, Smith’s and Windmill Islands were completely gone.

Francis J. Ryan is Professor and Director of American Studies at La Salle University. He was born and raised in the Harrowgate section of Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- PhilaPlace: From Wetland to Urban Land, A Social and Environmental History of Philadelphia's Tidal Islands (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Soupy Island (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Philadelphia's Lost Island(s) (Naked Philly)

- Delaware River Images: Smith and Windmill Islands (Philly H2O)

- Islands on the Delaware (New Jersey Skylands)