Sugar and Sugar Refining

By Lisa Minardi

Essay

Fueled by extensive trade with sugar islands in the Caribbean, Philadelphia became a leading center of sugar refining in colonial America. Although the city lost its dominance of the industry to New York by the end of the eighteenth century, local sugar refining continued to expand, particularly under the Pennsylvania Sugar Refining Company (“Penn Sugar”). The rise of national sugar conglomerates and increasing production of sugar extracted from sugar beets proved to be insurmountable challenges, however. After acquisition by the National Sugar Refining Company in 1947, the Penn Sugar refinery closed in 1984. Its legacy briefly revived in 2010 with the naming of the SugarHouse Casino, but only until rebranding changed the name to Rivers Casino Philadelphia in 2019.

Philadelphia’s early dominance as a principal seaport gave the city ready access to sugar. The type of sugar consumed and refined in early Philadelphia was extracted from sugar cane, a plant that grows only in tropical and subtropical zones. At the time, most sugar plantations were located in the Caribbean, where enslaved Africans worked under brutal conditions to harvest tough sugar cane stalks with sharp blades. Extracting the sugary juice of the cane before it spoiled required the cane to be immediately crushed or run through a roller mill. The liquid was then heated to evaporate liquid and concentrate the sucrose. This raw sugar was next packed into wooden casks and transported to cities such as Philadelphia, where it was refined—a labor-intensive process of cooling and heating the sugar repeatedly to remove impurities and produce a finer, whiter sugar. Philadelphia’s status as a center of transatlantic commerce and the availability of laborers—including European immigrants, free Blacks, and enslaved people—made it a desirable location for sugar refining.

Philadelphia consumers had access to a wide range of sugar products. The coarsest and least expensive was raw brown muscavado, a product left over after draining off molasses during the first stage of refining. Consumers also could buy single- and double-refined “loaf” sugar, formed in earthenware cones at sugar refineries by successive rounds of boiling and evaporation. To use the sugar loaves, which were rock hard, required wielding implements including steel nippers and hammers to break the sugar into smaller chunks. Another laborious process made granulated sugar and powdered sugar by crushing the chunks of sugar in a mortar and pestle to the desired size, using a fine sieve as needed to separate varying sizes.

Sugar also played an important role in social rituals. In formal settings or social occasions such as taking tea, wealthy Philadelphians used delicate silver tongs to pick up sugar chunks from a sugar bowl in order to sweeten a cup of tea. Sugar bowls, often made from costly materials such as silver and porcelain, sometimes came with larger tea services that also included teapots, cream jugs, cups, and saucers. Specialized tea tables became a popular furniture form, made of either tropical mahogany or local hardwoods such as black walnut. These tables typically had a tripod base and a circular top that swiveled for ease of use and could also be flipped up to store against a wall when not in use.

Riverfront Refineries

By the mid-1700s, Philadelphia had become one of the leading centers of sugar refining in colonial America. Philadelphia sugar refiners (also known as “sugar bakers”) included both English- and German-speaking people, many of them merchants engaged in transatlantic trade who saw an opportunity to increase profits by refining the raw sugar they were importing. Many of these early refineries were located near the waterfront, with convenient access to the wharves where the heavy barrels of raw sugar were unloaded. In 1772, merchant William Coats advertised “loaf, lump, and muscovado SUGARS” in addition to rum, wines, indigo, and spices at his store, identified by the “sign of the Sugar-Loaf.” His handbill depicted the store’s interior, with numerous loaves of sugar prominently arranged in the middle. Another Philadelphia merchant, Edward Pennington (1726–96), kept a notebook in which he compiled “Observations on Making Sugar.” He noted consumers’ preference for white sugar and advocated using more water during the refining process. Prominent Germans also invested in sugar refineries, including David Schaeffer (d. 1787) and his son-in-law Frederick Muhlenberg (1750–1801). After Schaeffer’s death in 1787, Muhlenberg bought out his brothers-in-law’s shares in the sugar refinery and formed a partnership with Jacob Lawerswyler. The business initially thrived, but was terminated in 1799 due to intense competition and the devastating loss of a ship, the Golden Hind, of which Muhlenberg was part-owner.

By the 1830s, pro-abolitionists in Philadelphia sought to find alternatives to cane sugar due to its reliance on enslaved labor. Sugar beets offered a promising alternative as they could be grown in temperate climates. This prospect gained plausibility after 1747, when German chemist Andreas Marggraf (1709–82) discovered that the sucrose contained in beets was indistinguishable from that in sugar cane. His protégé, Franz Karl Achard (1753–1821), discovered a method of extracting the sucrose from beets to make sugar. Philadelphians founded a Beet Sugar Society in 1836, but it failed due to the poor quality of the product. (Beet sugar later found success in California and by the twenty-first century about half of all sugar produced in the United States came from sugar beets.)

Philadelphia encountered increasing competition in the sugar industry during the nineteenth century, especially in major port cities with an abundance of labor. By 1810, sugar refineries had opened in Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and Alexandria, Virginia. By the late 1800s, New York, the nation’s greatest port, dominated the industry. New York became home to the largest sugar refinery in the world after an 1882 fire destroyed an earlier plant (est. 1852) and spurred construction of a massive, ten-story structure and sprawling industrial complex in Brooklyn—the American Sugar Refining Company. Owned largely by the wealthy Havemeyer family, American Sugar became the largest manufacturer in the United States.

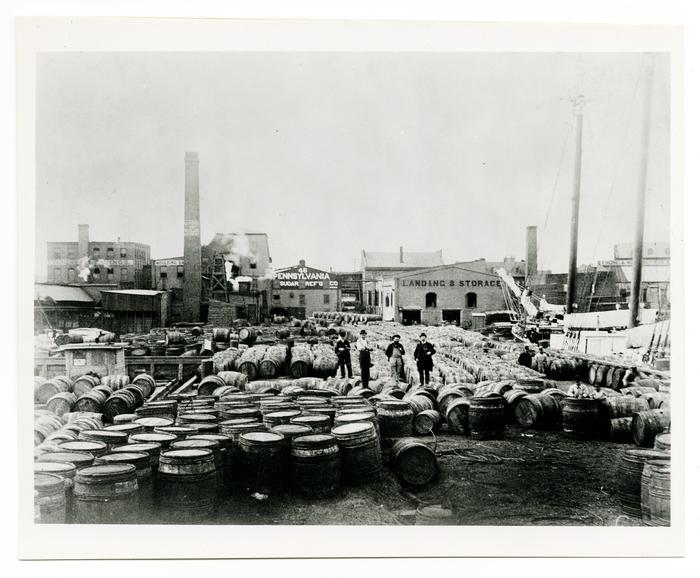

Philadelphia, meanwhile, became the base of operations for large sugar refineries such as the Pennsylvania Sugar Refining Company (“Penn Sugar”). Founded in 1868 by German immigrant John Hilgert (1807–81)at Fifth and Girard Streets, the company moved in 1881 to the base of Shackamaxon Street along the Delaware River in the city’s Fishtown section. There, under the leadership of John Hilgert’s son Charles, the company repurposed an earlier whale oil works into a sugar refinery. By the 1950s, the refinery had grown into a massive complex with eighteen buildings and more than 1,500 male and female employees. Former workers recalled that by that time, most or all of the employees were white, although of varying ethnic backgrounds; previously, during the Second World War, the company had employed many African Americans. In an industrial-scale version of the eighteenth-century process, ships unloaded huge quantities of dark brown, raw sugar (imported from both the Caribbean and now the Pacific basin islands) at Penn Sugar’s wharf along the Delaware. The refinery’s melter house converted the sugar into a thick syrup, then filtered and piped to the pan house to be crystallized, washed, and dried. The refined sugar was then pressed into cubes or packed it into bags, boxes, or large wooden barrels, while pulverizing the rest into powdered sugar. The remnants became black-strap molasses or could used to make solvents, flavorings, and even antifreeze.

The Decline of Sugar Refining

During the twentieth century, Philadelphia’s once-thriving sugar refining industry suffered in the face of stiff competition from massive sugar conglomerates and the production of sugar extracted from sugar beets. In 1947, the New York-based National Sugar Refining Company, also known as Jack Frost, acquired Penn Sugar. The local refinery remained active until 1981, when Jack Frost filed for bankruptcy. Unable to buy raw sugar, the company laid off its six hundred Philadelphia employees.

The Penn Sugar site lay dormant until it was reborn through adaptive reuse as the SugarHouse Casino, which opened in 2010 (renamed Rivers Casino Philadelphia in 2019). The former refinery’s waterfront location, once a practical necessity, made it appealing for urban redevelopment along the Delaware River. The casino is just one example of Philadelphia’s former sugar refineries being repurposed for new uses; the Sugar Refinery Apartments were one of the first industrial warehouse sites converted to residential use in the Old City historic district.

Although Philadelphia’s once-thriving sugar refineries disappeared by the late twentieth century, the industry was a major part of the city’s industrial heritage. While no longer actively used for manufacturing, the few remaining physical traces of once-bustling sugar refineries indicate the vast scale of the sugar refining industry.

Lisa Minardi is executive director of Historic Trappe and a Ph.D. candidate in the History of American Civilization program at the University of Delaware, where she is studying the German community of early Philadelphia for her dissertation. Her publications include numerous books and articles on Pennsylvania furniture, architecture, and folk art. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University