Trails (Recreational)

Essay

An expanding network of recreational paths for walkers, hikers, cyclists, joggers, and commuters serves the Greater Philadelphia region. The first recreational paths date to the mid-nineteenth century, when upper-class residents sought idyllic walking grounds in rural cemeteries and urban parks. In the twentieth century, grassroots hiking clubs built additional footpaths, but by the early twenty-first century governments and large contractors stepped in to create new multiple-use paths with state and federal funding.

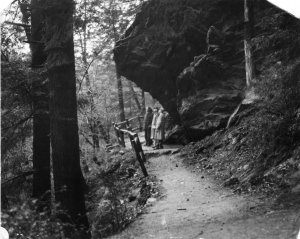

Walking, long a necessity of everyday life, also became viewed as a recreational activity in the middle to late nineteenth century. The invention of the telephone, advances in public transportation—first omnibuses, then cable cars and electric trolleys—and the emergence of a middle class that did less physical labor allowed some Americans to re-envision walking as something pleasurable and therapeutic. These potential hikers were also those most likely to be influenced by new ideas about the natural world portrayed in Romantic paintings of pastoral landscapes, Transcendental writings about the spiritual value of nature, and the aesthetics of rural cemeteries such as Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill and urban greenways such as Fairmount Park, which contained some of the first designed walking paths. Like many late nineteenth-century Americans, these new walkers formalized their interests by founding clubs.

Hiking clubs—and the trails they built—came relatively late to the Philadelphia region. Early outing clubs, such as the Boston-based Appalachian Mountain Club (1876) and the San Francisco-based Sierra Club (1892), had thousands of members by the time a group of influential newspaper publishers and businessmen founded Pennsylvania’s first hiking club, the Pennsylvania Alpine Club, in 1917. Based in Harrisburg, the Alpine Club lobbied the state legislature to enact conservation measures related to outdoor recreation, forestry, and wildlife protection. The club also constructed the Darlington Trail, the state’s first modern hiking trail, west of Harrisburg.

Hiking Broad Street

During the next several decades, middle-class hikers founded at least a dozen regional clubs throughout Pennsylvania, including the Philadelphia region. In 1928, the Back-to-Nature club emerged from a series of walks the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin organized as part of a “correct posture campaign.” The first hikes led groups of more than 500 people up and down Broad Street before the organizers realized that the hikers would be safer walking along the paths in Fairmount Park, nearby rural roads, and the more-distant Appalachian Trail. In 1961, the club constructed the fifty-mile Batona Trail across New Jersey’s Pine Barrens.

Other hiking clubs were attracted to trail building even earlier. The New York–New Jersey Trail Conference, originally founded in 1920 as the Palisades Interstate Trail Conference, played an instrumental role in building the early Appalachian Trail from New York City, across New Jersey, and into Pennsylvania. The Philadelphia Trail Club organized regular trips to the Appalachian Trail, some seventy miles to the north, to maintain a section of the rocky, ridgeline path between the Delaware and Lehigh Rivers. In contrast, the Horse Shoe Trail Club, a suburban-based club founded by Henry Woolman (d. 1951) in 1934, decided to build its own trail linking Valley Forge to the Appalachian Trail near Harrisburg. In addition to volunteer labor from the region’s hiking clubs, Woolman secured assistance from the National Youth Administration for the Depression-era project. As the name suggests, the 140-mile trail was opened to both equestrians and hikers.

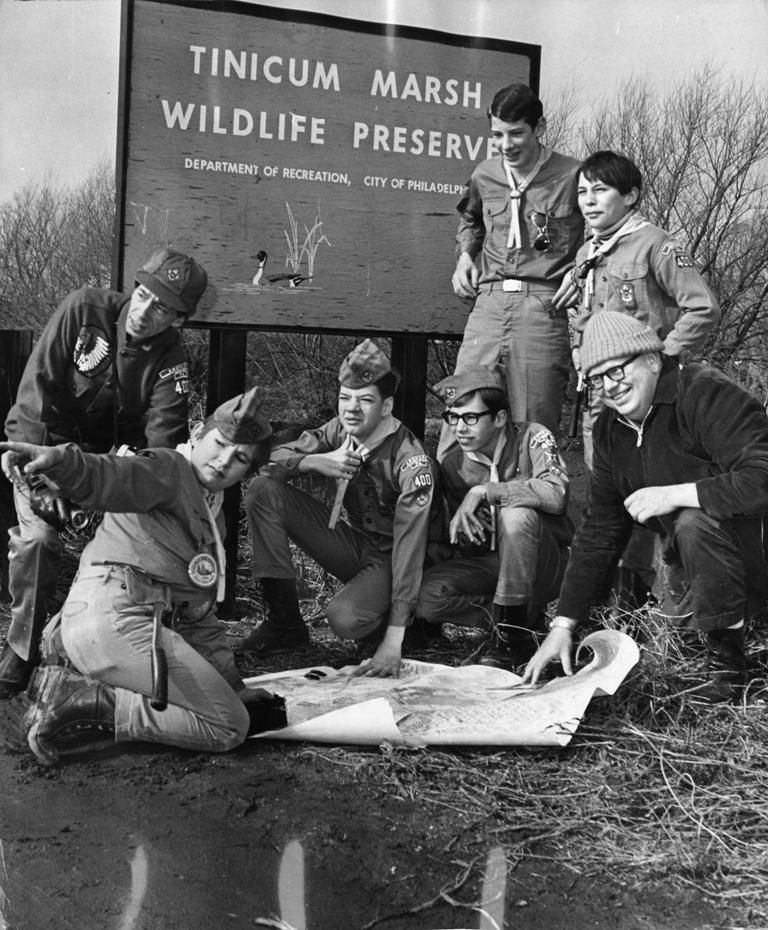

In the post-World War II period, the popularity of hiking increased dramatically as new outfitting materials such as nylon and aluminum, dehydrated foods, higher rates of automobile ownership, interstate highway construction, and the expansion of the state and national park systems made hiking more comfortable and convenient. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the rise of the environmental movement, promoted by grassroots hiking clubs and institutionalized in federal legislation and funding, added new meanings to time spent in the woods. In response to the rising demand, state agencies and volunteer organizations created more and more trails in parks throughout the region.

Trail Surge in the 1980s

During the 1980s, a major shift occurred in the region’s trail activity, as well-groomed, multiple-use trails appealing to cyclists and walkers of all abilities grew in popularity. In part, the shift resulted from policymakers’ evolving understanding of trails’ positive benefits for economic development, public health, alternative transportation, and ecological functions such as storm-water management. Greater Philadelphia was well-suited to take advantage of these new ideas. The region’s post-industrial infrastructure of abandoned canal towpaths and railroad rights-of-way offered clear, level, and well-engineered corridors for recreational trails.

The Schuylkill River Trail, begun in 1979 by the Schuylkill Greenway Association, followed sections of towpath and railroad beds for 130 miles toward Pottstown, Reading, and beyond. Along the Delaware River, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania preserved the anthracite-coal canal as a state park in the early 1950s, and, beginning in the 1980s, the towpath was re-envisioned as part of a larger trail system that would follow the Delaware and Lehigh rivers 165 miles north to Wilkes-Barre. Later studies showed that the two trails combined annually attracted more than one million users and generated at least $25 million for the region’s economy. Most trails were shorter in length and relatively local in their impact. In 1978, for example, Montgomery County purchased an abandoned railroad corridor that became the nineteen-mile Perkiomen Trail. It took twenty-five years to complete but quickly became one of the region’s most popular trails for walking and biking.

In the early twenty-first century, the trails movement once again experienced a major turning point. A coalition of environmental and bicycle advocacy groups, spearheaded by the Pennsylvania Environmental Council, the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, and the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, successfully advanced a vision for an interconnected, 275-mile network of multiuse trails throughout southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey. In 2010, the coalition secured a $23 million grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation to complement nearly $33 million invested by the William Penn Foundation during the previous twenty years. Along with state grants from the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation & Natural Resources, this funding allowed the coalition to fund priority trail projects, brand the emerging network of trails as “The Circuit,” and launch a sophisticated fundraising campaign that sought hundreds of millions of dollars to complete more than 450 miles of trails.

Silas Chamberlin holds a doctorate in environmental history from Lehigh University and currently serves as a regional adviser in the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation & Natural Resources. His dissertation, “On the Trail: A History of American Hiking,” is the first comprehensive, national history of the hiking and trails community from the early nineteenth century to the late twentieth century, and his research on trails, hiking, and outdoor recreation has appeared in Pennsylvania History and Landscape Architecture Magazine. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Delaware's new rail trail connects 75 miles of trails (WHYY, September 10, 2012)

- Schuylkill Project shoots for 2014 Manayunk Bridge trail completion, maintains focus on Venice Island and the canal (WHYY, January 30, 2013)

- Delaware senator introduces hiking trail legislation at Cape Henlopen (WHYY, April 23, 2014)

- $18M grant for Circuit Trails project will help connect cyclists in Montco to the Morris Arboretum (WHYY, January 1, 2020)

Links

- A Winter's Walk Around East Park Reservoir (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- A New Life for Old Fairmount Park (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Appalachian Trail Conservancy

- BATONA (BAck TO NAture) Hiking Club

- City of Philadelphia Parks & Recreation

- The Philadelphia Trail Club

- Philly is the first major U.S. city to map its trail network with Google (Grid, June 30, 2016)