United States Colored Troops

Essay

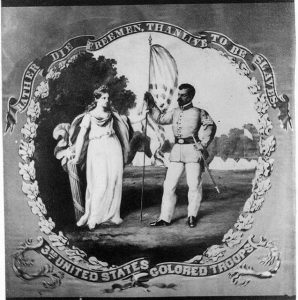

During the American Civil War (1861-65), Philadelphians raised eleven regiments of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). This division of the United States Army, consisting of Black soldiers led by white officers, provided much-needed manpower for federal forces in the final two years of the war.

When the Civil War began, many African Americans across the North sought to enlist, motivated by their belief that their military service would help win the war, end slavery, and entitle them to rights that they were denied—the rights to vote, sit on juries, and testify against whites in court. Most whites opposed blacks serving in the army, believing that defending the republic was an essential element of citizenship reserved for white men only. Also, the federal Militia Act of 1792 prohibited Black men from serving in the militia.

By the summer of 1862, as casualties mounted from combat and disease and as fewer white men enlisted, northern public opinion moved in favor of enrolling Black men in the army. On July 16, 1862, Congress passed the Second Militia Act, which allowed African Americans to be employed as soldiers, and in early 1863, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton (1814-69) authorized the governors of Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut to organize Black regiments. Massachusetts was the first state to raise two regiments—the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Voluntary Infantry Regiments. About three hundred Black Philadelphians enlisted in these regiments. One company of the 54th was raised in Philadelphia.

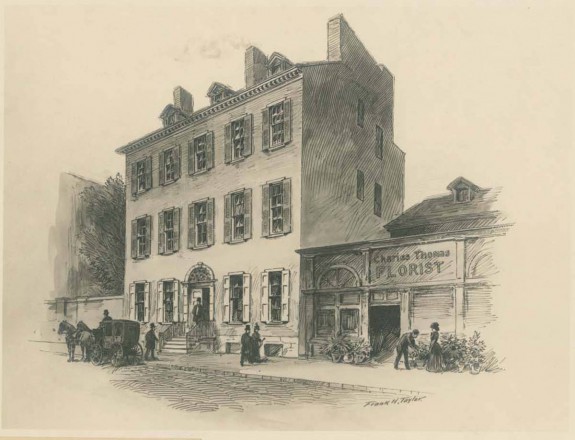

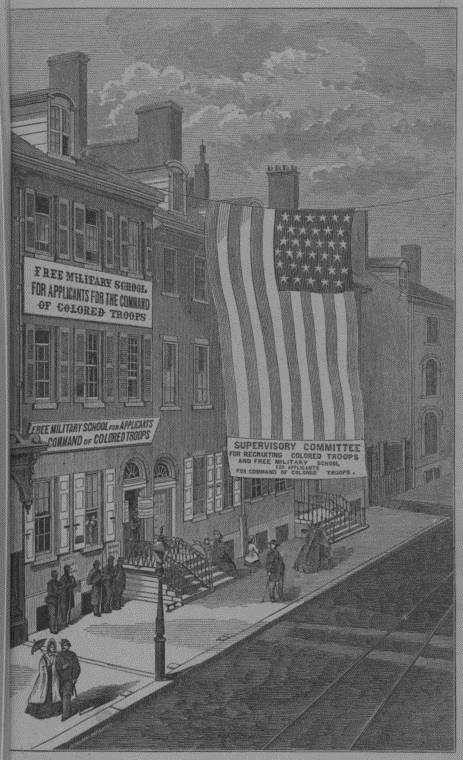

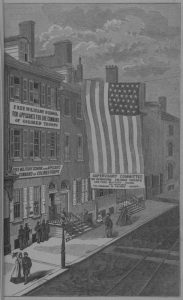

In May 1863, the War Department established the Bureau of Colored Troops, which facilitated Black enlistment throughout the country and sent Major George Stearns (1809-67) to Philadelphia to raise Black regiments. The local Union League—founded by elite white Philadelphians to foster support for the Union war effort—established a Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Troops and received Secretary Stanton’s permission to begin raising Black regiments with the aid of local and national Black leaders such as Octavius V. Catto (1839-71), Jacob C. White (1837-1900), and Frederick Douglass (c. 1815-95). Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church and its denominational newspaper, The Christian Recorder, also encouraged Black men to enlist. Federal officials and local leaders (Black and white) campaigned extensively to attract Black recruits in Philadelphia, from Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery and other counties in Pennsylvania, and from in Delaware, New Jersey, and New York.

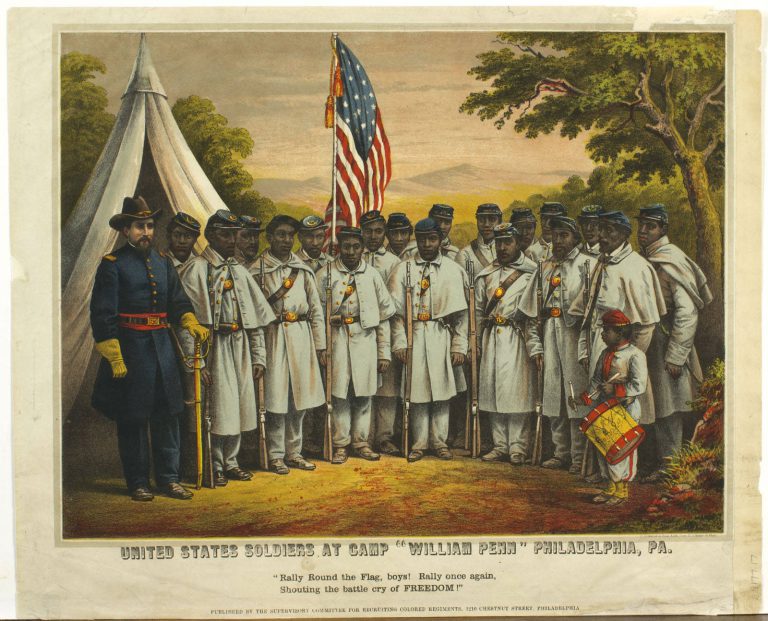

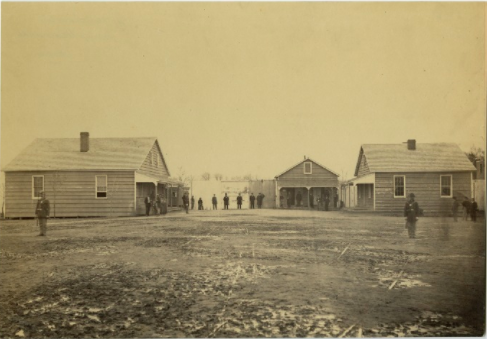

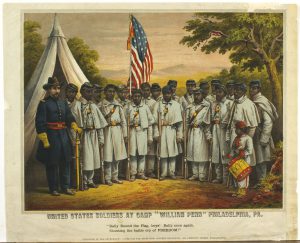

Training at Camp William Penn

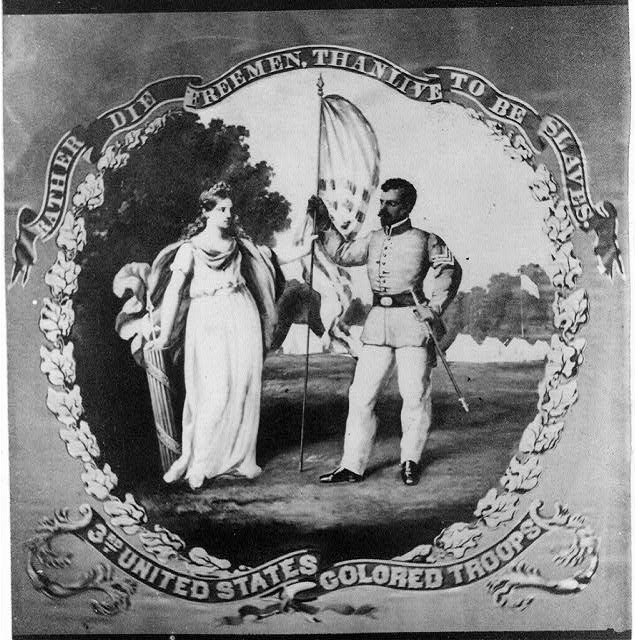

Eleven USCT regiments were raised in Philadelphia—the 3rd, 6th, 8th, 22nd, 24th, 25th, 32nd, 41st, 43rd, and 45th, and 127th—totaling 10,940 men. These recruits trained eight miles north of the city at Camp William Penn, where they practiced weaponry, tactical formations and maneuvers, and guard duties. For these soldiers, weekdays began at 6 a.m. with reveille and roll call, followed drills throughout the day and evening, and leading to a dress parade and then taps at 9 p.m. On Saturdays the men cleaned the camp, and on Sundays they assembled for inspection, attended a church service, and participated in dress parades.

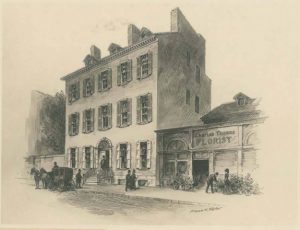

Many white men seeking to become commissioned officers in the USCT regiments received training from the Free Military School for Applicants for the Command of Colored Regiments, formed by the Union League’s recruiting committee, which operated from December 26, 1863, through most of 1864. Black men were not admitted to the school because most northern whites believed that Black men were not capable or intelligent enough for command, but an auxiliary school trained blacks as noncommissioned officers.

The first Black regiments from the Philadelphia region, led by their white officers, arrived in the South in the summer of 1863 and participated in many of the major campaigns of the final two years of the war. Their engagements included the assaults on Fort Wagner and Fort Gregg (August 20-September 7, 1863); Richmond-Petersburg Campaign (June 1864-March 1865) in Virginia; the Battle of Olustee, also known as Ocean Pond (February 20, 1864) in the swamps of north Florida; and the Battle of Honey Hill (November 30, 1864) in South Carolina. The 41st Infantry Regiment USCT, which arrived in Virginia in the fall of 1864, contributed to the Union victory in the Appomattox Campaign that culminated April 9, 1865, with the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia under Confederate General Robert E. Lee (1807-70) to Union General Ulysses S. Grant (1822-85) at Appomattox Court House.

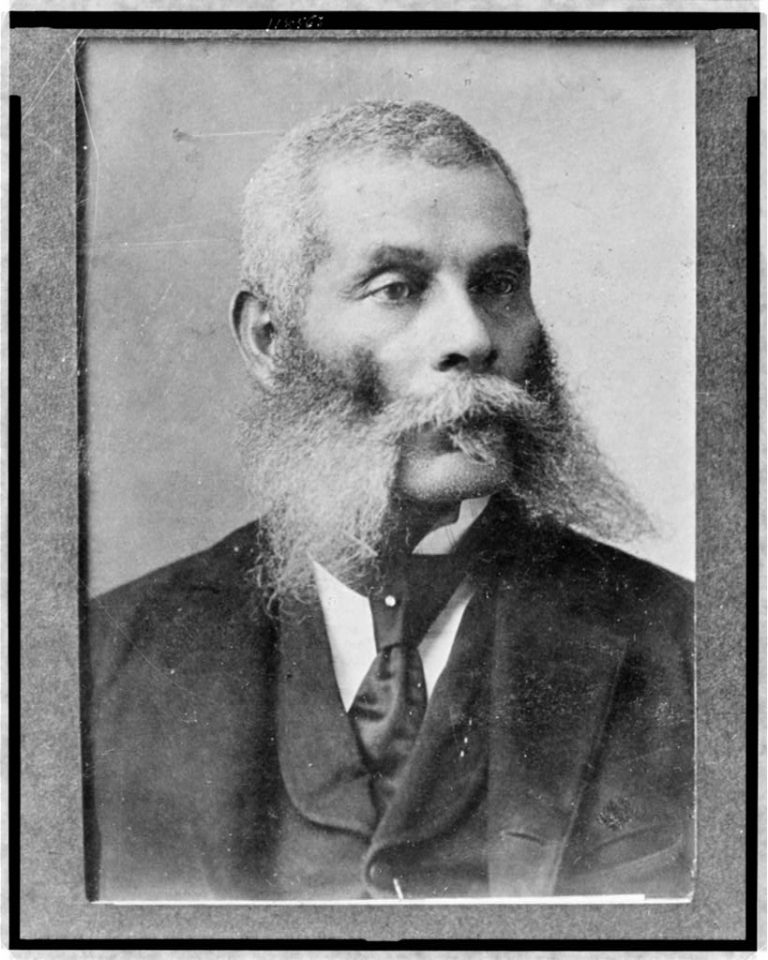

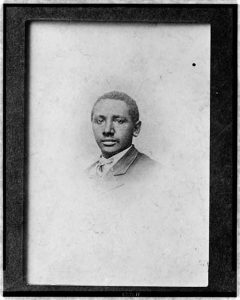

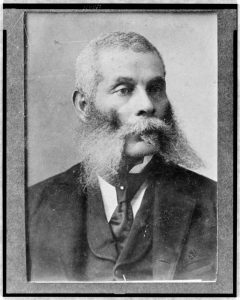

Two Medals of Honor

Many local service men in USCT regiments earned recognition for their distinction in battle. Sergeants Alexander Kelly (1840-1907) and Thomas R. Hawkins (1840-70) from the 6th USCT received the Congressional Medal of Honor for their heroism in rescuing the regimental colors while under heavy fire at the Battle of New Market Heights, Virginia (September 28-29, 1864). Kelly was also praised for rallying the men in his company during a period of confusion on the battlefield.

Military service did not guarantee equal treatment for African Americans on the battlefield or at home. For example, African American solders received pay of only ten dollars per month, with three dollars deducted for clothing, while white privates received thirteen dollars per month plus a clothing allowance. Many Black soldiers expressed their dissatisfaction by refusing to accept the reduced rate and went for more than a year without pay. Not until June 15, 1864—when many Black regiments teetered on the brink of mutiny—did Congress pass legislation that equalized the pay of Black and white soldiers and offered back pay to those who refused their pay or were underpaid.

At home, Black troops and African American women who provided aid and comfort to wounded soldiers faced discrimination. During the period of the Civil War, African Americans and their white abolitionist allies battled discrimination on Philadelphia’s streetcars, where African Americans were excluded from riding or forced to ride on the front platforms. After the war, in March 1867, the campaign led to the state legislature prohibiting segregation on all forms of public transportation in the state.

By early December 1865, most of the USCT regiments that had trained at Camp William Penn returned to Philadelphia and received a heroes’ welcome for their service and sacrifice. When the 25th USCT returned to the city, the regiment attended a parade and flag-dedication ceremony at the Union League before being officially mustered out of service. Military service allowed African Americans establish their claims to full citizenship in Pennsylvania.

Lucien Holness is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Maryland-College Park. His research interests include African American and Atlantic history. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History