Painted Fire Hat

By Erin Bernard

Artifact

Drag across the screen to turn the object. Zoom to view details.

Read more below.

Essay

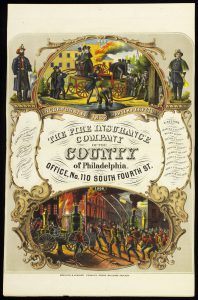

Parade Fire Hat, 1847. (Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, gift of the Honorable Glover C. Lander, 1945, Photograph by Sara Hawken)

With the elegance of a beaver top hat and the patriotic imagery expected of the military, this colorful painted, pressed-felt parade fire hat features an eagle stretching its wings while standing on a red, white, and blue shield by the ocean. David Bustill Bowser (1820-1900) painted this hat for the United States Fire Company in 1847. During a period when firemen were perpetrators of mayhem who ignored their company by-laws by stealing hoses, disassembling fire carriages, and even shooting guns on neighborhood streets, they also were celebrated volunteers who saved lives and marched in parades. As historians Amy S. Greenberg and Mark Tebeau have illuminated, the politics of nineteenth-century fire suppression were riddled with ironies of civil service and deviance. What is particularly curious about this fire hat, though, is the intersection of these politics and the legacy of its painter.

A son of Jeremiah Bowser (1766-1856), a fugitive slave who became a Quaker elder and oyster-house keeper, David Bustill Bowser grew up in Philadelphia with radical roots that nurtured his growth as both an artist and politically-engaged citizen. Renowned family members included cousins Frederick Douglass (1818-95) and Sarah Mapps Douglass (1806-82), as well as grandfather Cyrus Bustill (1732-1806), a founder of the Free African Society. Like others in his family, Bowser was politically engaged. In 1860 he lobbied the state against streetcar segregation and railroad harassment as part of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League, and in 1863 he signed a broadside written by Philadelphia’s Committee for the Recruitment of Colored Troops. While most active in the United Order of Odd Fellows, in 1866 Bowser also became a charter member of the Union League of America. In 1878 he created a connection between blacks in Philadelphia and those in Vicksburg and New Orleans through his fund-raising work for the Yellow Fever Relief Committee of Philadelphia.

Bowser began his painting career under the guidance of a relative, his cousin Robert Douglass Jr. (1809-87), a respected and skilled sign painter, lithographer, and portrait artist. While Aston Gonzalez’s biography of Robert Douglass Jr. mentions little of his alleged studies under American painter Thomas Sully (1783-1872), it does illuminate his experience as one of the first African Americans to exhibit an oil painting within the walls of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). Despite this success, Douglass was unable to view his work at PAFA because of his skin color. Instead, he travelled to London to study the great masters at the National Gallery and the British Museum. It seems Douglass chose to portray subjects in his work which reflected his political stance, blending activism with his formalist training.

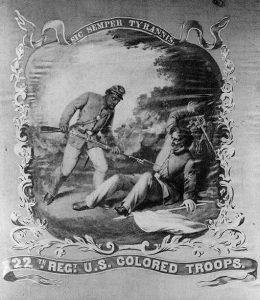

As an artist, Bowser is perhaps best known as a portraitist of President Abraham Lincoln (1809-65), whom he painted twenty-one times. In 1941, one of these portraits was found in a barn near the Robert Purvis (1810-98) family home, a stop along the Underground Railroad in Byberry, Pa., but it was not publicly exhibited until 1981 in an exhibition titled Of Color, Humanitas and Statehood: The Black Experience in Pennsylvania over Three Centuries, 1681-1891, curated by Charles Blockson at the museum later known as the African American Museum in Philadelphia. A number of the Lincoln became part of public and private collections, including Adamson-Duvannes Galleries in California. Bowser also painted John Brown (1800-59), the white abolitionist who, in 1859, led an armed raid of Harpers Ferry’s federal armory and was consequently executed. After the Emancipation Proclamation, Bowser also was commissioned to create banners for black Union regiments who trained at Camp William Penn, located northwest of the city adjacent to the estate and Underground Railroad refuge of Lucretia Mott (1793-1880). Bowser’s painting Lincoln and Female Slave (1863) became revered for its unusual depiction of Lincoln, likely announcing the Emancipation Proclamation, with an enslaved African woman as the focal point of the work at a time when other painters did not often feature black women together with Lincoln.

While historians may use Bowser’s subject matter as a lens to evaluate his politics and race, equally important is his attention to detail and overall aesthetics. Bowser’s fire hat is considerably more intricate than others of the time period. Bowser’s detailed scenes of patriotism, in tandem with his portraiture skills, offer stylistic hints of both his cousin Douglass and teacher and artist Thomas Sully. Sully’s 1819 rendition of Washington’s crossing, Passage of the Delaware, with its clouds textured with greys and pinks, could easily have influenced Bowser’s fire hat palate, although Sully’s work appears more realistic due to fine brush strokes and deliberate use of lighting. Bowser’s later works, including his banner for the Twenty-Second Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops, demonstrated a more realistic touch and finer brush stroke, while the fire hat’s eagle was more caricatured and stylized. On most fire hats, the initials of owner were marked on top. This fire hat’s initials are T.C.C., but the identity of the person who wore the hat is unknown.

Bowser painted this hat for the United States Fire Company, established in 1811, sixty years before Philadelphia professionalized firefighting with a citywide paid department. Operating from a firehouse at Second Street and Peggs Run (the Cohoquinoque Creek) near Spring Garden Street, the United States Fire Company was not Philadelphia’s first cohort of firemen, nor was it the last. Volunteer fighting companies originated with the Union Fire Company formed by Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) in 1736 and grew in numbers through the early nineteenth-century, partly in reaction to the flammability of Philadelphia’s industrial spaces, especially textile mills. Fire companies attempt to instill order in their ranks with charters visions and by-laws even before the riotous years of the 1830 and 1840. Large events of civil discord at, for instance, Pennsylvania Hall, in Kensington, and along Lombard Street, demanded attention from firemen who quelled flames in keeping with civilian safety and their political beliefs. According to scholar Ken Finkel, in the years following, firemen also rioted amongst themselves and drew strong public criticism for their behavior. In 1854, an altercation between two gangs from the Taylor Hose and Hibernia fire companies resulted in a shoot out; a stray bullet entered a third-story window and nearly struck an infant.

A harsh view of nineteenth-century Philadelphia firemen is fairly common in historical documents, although this view was not often documented by firemen themselves. In an address written for the thirty-sixth anniversary of the United States Fire Company in October 1847, “a member” echoed critical sentiments about Philadelphia companies. Selected by a committee of U.S. Fire Company Members, the author—not named in the document—reflected on his twenty years with the department, beginning with a lament that Philadelphia firemen had lost something—”a reputation.” He wrote that Philadelphia firemen, in living a life of service, had civil duties that did not match their current behaviors. “There is such a manifest dereliction from the duty in the behavior of firemen at the present day—and that dereliction is so entirely at variance with the by-gone reputation of the department,” he wrote. This member was concerned not only with the duty of firemen but also with the behavior of all men in society as he spoke against violence, including a refutation of anyone who celebrated the bloodshed of the Mexican-American War (1846-48). He also used the Bible to prove his point; he wrote in all capital letters “THOU SHALT NOT KILL.”

At the end of the speech, the request to his brethren was clear. “We separate with the ardent hope that each one will be the first to exercise an influence to being back to its primitive good the PHILADELPHIA FIRE DEPARTMENT—that our sister cities may no longer jeer us as rowdies, ruffians, and rioters, that our own citizens may again find a willingness on their part of some to retain the integrity that we all know and feel belongs to well-behaved well-disposed united firemen,” he stated. In his language about the virtues of wisdom and courage within the city, this member wanted Philadelphia firemen to change their actions to match their duties. This October 1847 speech could have been issued at the moment the United States Fire Company donned Bowser’s fire hats on parade, connecting a moment of potential reform among Philadelphia firefighters with the artwork of an elite abolitionist.

Text by Erin Bernard, who earned her M.A. in history at Temple University. She is the founder and curator of the Philadelphia History Truck. Bernard is an Adjunct Professor of History at Moore College of Art and Design as well as Senior Lecturer of Museum Studies at the University of the Arts.