Street Sign

Artifact

Drag across the screen to turn the object. Zoom to view details.

Read more below.

Essay

Street sign, c. 1950. (Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection, Photograph by Sara Hawken)

By the early twenty-first century, Philadelphia had more than 3,600 distinct named streets, alleys, lanes, places, boulevards, expressways, roads, courts, mews, and avenues. The city Streets Department maintained 2,180 miles of city streets, 35 miles of roads in Fairmount Park, and 360 miles of state highways, which created about 24,000 traffic intersections in the city.

In this maze of streets, how do we know where we are? How do we find our way to where we want to go? Street name signs, one of the many types of signs found on urban streets, point the way and provide direction and order in our lives.

This cast iron sign from the intersection of Paschall Avenue and South Forty-Eighth Street in Philadelphia’s Ward 40 is an example of one such guide. This artifact was mounted on the top of a sign pole standing on the southeast corner of the intersection, oriented so that each nameplate was parallel to the street it named. Rotating the sign on this page shows that one side of each nameplate became more corroded from prevailing weather conditions. These nameplates were designed for easy visibility: the street names (odonyms) are spelled out in capital letters. The sign is spare in offering information, providing only the names of the two streets crossing each other at this intersection. Even compass directions are omitted: the sign does not indicate that this portion of Forty-Eighth Street is officially designated as South Forty-Eighth Street.

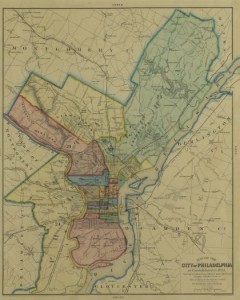

This physical artifact symbolically connects the intersection, originally in Kingsessing Township west of the Schuylkill River in the County of Philadelphia, to the original Philadelphia city grid laid out by Thomas Holme (1624-95) at the request of William Penn (1644-1718). When the surveyor superimposed a network of streets at right angles over the rural landscape of scattered farms, he was not documenting an existing landscape but envisioning orderly and comprehensible future urban development. Penn named the east-west streets after native trees and flora and numbered the north-south streets. The two exceptions were Broad and High Streets, the main north-south and east-west streets running through the center square.

In conjunction with maps and early travel guides, often called “stranger’s guides,” signs provided urban navigation assistance. The first street name signs were often carved into the masonry of buildings that stood at intersections. Later, wooden boards with street names were affixed to building walls. Rarely seen today in American cities, street names incised into masonry building walls or signs affixed to walls are still common in European cities. The author of A Handbook for the Stranger in Philadelphia of 1849 noted that “At the corners of the principal streets, will be noticed their names painted on a board, with the prefix of No. or So., as the case may be.” This comment also emphasized the challenges of navigating a city where often less-prominent streets or newer blocks had no signs at all.

After the 1854 Act of Consolidation enlarged the city, civil engineer A. E. Rogerson published the fourteen-page Alphabetical List of the Streets in the City of Philadelphia (1859), listing streets and giving locations by identifying their easternmost point. He also provided a second table of street name changes. Sign changes, though, often lagged behind name changes, so signs could be undependable guides. For this reason, the author of the 1849 stranger’s guide had suggested that visitors might have to figure out on a map where they were and where they wanted to go, then count the blocks as they walked. Numbered streets were of course easier to track than streets otherwise named, where pedestrians could easily lose count and thus their sense of place.

In the enlarged industrial city of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this inconsistent and incomplete system of street name signs caused even greater confusion. In her 1926 textbook on land planning, Harlean James (1877-1969) observed that street name signs in American cities were variously placed on walls of buildings, on lamp posts, on special posts of their own, or were often carved into curb stones, where people rarely noticed them. This latter type of sign was dangerous for pedestrians, who needed to look up rather than down, and useless for drivers.

By the 1920s, the automobile’s dominance of urban transportation demanded standardized road signs. In 1905, fewer than 500 automobiles were registered in Philadelphia; by 1918, there were 100,000. Urban planners paid greater attention to the design and placement of street name signs, emphasizing that signs should be easily visible to both pedestrians and drivers. In Philadelphia and other American cities, this prompted the change to street sign poles. For greatest visibility, overhead signs were eventually placed at the busiest intersections.

This street sign also represents a deeper history. Brought within the city’s boundaries by the Act of Consolidation, Forty-Eighth Street denotes the distance from the Delaware River – forty-eight blocks. Paschall Avenue traces its name to Paschallville, a village in lower Kingsessing Township established in 1810 by Dr. Henry Paschall, a physician and descendant of Thomas Paschal, who purchased 500 acres from William Penn. After the Act of Consolidation, the area developed gradually near the new Philadelphia and Darby passenger railroad line along Woodland Avenue, although the Gibson family, large Kingsessing landholders, held on to the farmland surrounding the future intersection.

Atlases documented quickening development of roads and residences in the 1880s. By 1892, an intersection existed at Forty-Eighth and Paschall and was surrounded on three corners by densely crowded blocks of rowhouses, built to house the employees of newly arriving companies to the vicinity, such as the Brill Street Car Co., Fels Naptha Soap, and then General Electric. The triangular northeast block, truncated by the diagonally running Grey’s Ferry Avenue, filled in by World War I.

The rectangular sign above dates from around the 1950s. About 1970, the city adopted a green six-sided sign, often affixed to street light poles, with space that allowed additional—but still legible–information. Signs indicated the block hundreds of the blocks flanking the intersection and, in some cases beginning in the 1990s, the identity of culturally or historically significant neighborhoods. Signs for Philadelphia’s Gayborhood, approved by Mayor John Street (b. 1943) in 2007, carried riders (a descriptive level of information below the street name designation) in a rainbow of colors. Street signs in Chinatown included riders with Chinese characters.

Visibility remained a concern. Beginning in 2012, new Philadelphia street signs featured Clearview font with a combination of upper- and lower-case lettering. The recyclable vinyl signs, made by city employees in the Sign Shop at G and Ramona Streets in Juniata Park (opened in 1958), had an average life expectancy of only seven to ten years.

In 2015, at the intersection of Pascall Avenue and South Forty-Eighth Street, green vinyl signs mounted on a utility pole on the southwest corner provided direction for drivers and pedestrians. But the intersection itself was altered. In the late twentieth century, the block of Forty-Eighth Street north of Paschall Avenue extending to Gray’s Ferry Avenue disappeared. The road could be detected, but after surrounding dwellings were demolished, it had partly vanished, as unused roads tend to do. On the southeast corner, the old iron pole and base of the circa 1950 sign were left rusting in front of several empty lots, forlorn indicators of deterioration.

Text by Anne E. Krulikowski, an Assistant Professor of History at West Chester University.