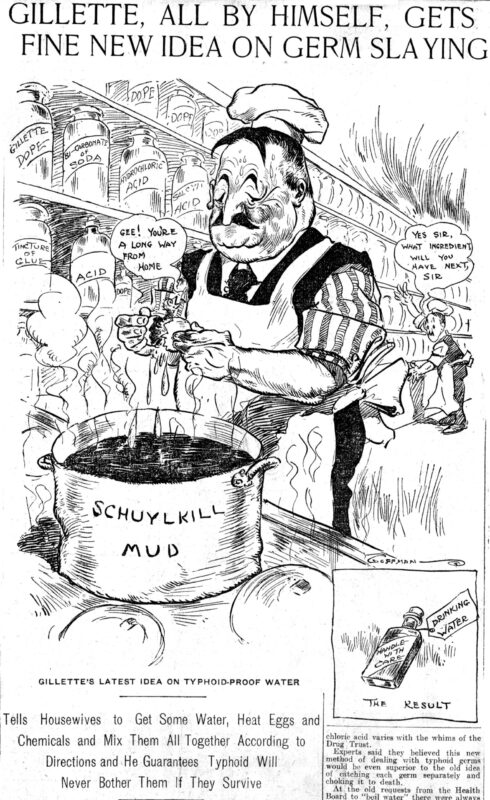

A special beauty of historical research lies in the many possibilities of unexpected discoveries. I was reminded of this when, searching for information about the Schuylkill River for a teacher workshop planned in conjunction with the release of the print volumes Greater Philadelphia: A New History for the 21st Century this month, I found this image, included here. I knew right away that this Mr. Gillette was not a relative and that his caricature was of no immediate interest to my task, but I couldn’t help but be curious about my namesake.

Immediate results were limited. Through an initial search, I managed to discover his name and title as Major Cassius Gillette, then a copy of an intriguing document recording Secretary of War William Howard Taft’s request of Congress for permission to detail him from the Army Corps of Engineers to serve as the chief engineer of Philadelphia’s bureau of filtration. Permission was apparently given, but his experience in the position appears to have been anything but ideal.

Other sources told me that Gillette served for less than a year, from 1906 to 1907. Checking Gillette’s name on the Philadelphia Water Department’s historical website, I was led to a series of news articles about his tenure. The collected clippings don’t cover all the details, but they do indicate that Gillette ran afoul with politically connected contractors, most notably, Daniel McNichol, whom he accused of overcharging the city by some two million dollars for work on the Torresdale filtration plant as it approached completion under Gillette’s direction. McNichol was not without allies, and many clippings accumulated by the Water Department accuse Gillette of incompetence. Such commentary aligned with the city’s notorious political machine, but it also drew the complaint of a reader who charged that Gillette’s imposition of water meters was forcing citizens to “pay for mud in liquid state.” Clearly this tempest in a teapot fit well within muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffen’s famous characterization of the city at the time as “corrupt and contented.”

Now known as the Samuel S. Baxter Treatment Plant, the Torresdale facility continues to serve a critical function in making drinking water drawn from the Delaware River safe to drink. For his part, Gillette remained in Philadelphia until his death in 1917, having concluded, it seems, that despite the tribulations of his short career in the city, he would rather be in Philadelphia than not.