Art of Cecilia Beaux

Essay

The elegant portraits of Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) found unanimous critical acclaim in Philadelphia, Paris, and New York. Her modern style of painting combined the best of academic training, European sophistication, and experimentation. Beaux successfully negotiated the gender separatism of the late nineteenth century while she gained international renown, allowing her to become the first full-time woman instructor at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

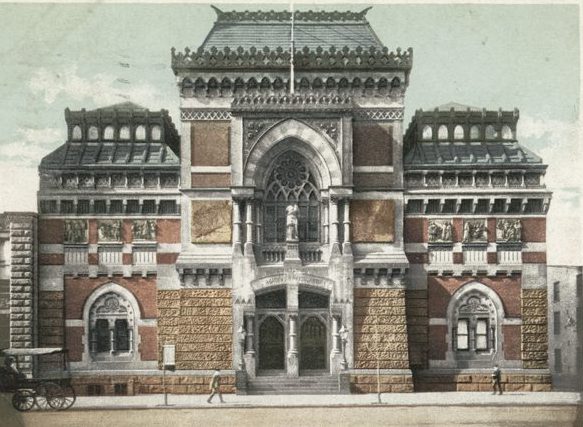

Beaux’s maternal relatives taught her how to copy lithographs and took her to exhibitions at the premier art venue in the city, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), as part of their tutoring. Cecilia was raised by her grandmother Cecilia Kent Leavitt and her aunt Emily and uncle William Biddle after the early death of her mother Cecilia Kent Leavitt Beaux (1822-55) and the return of her inconsolable father Jean Adolphe Beaux (1810-84) to France. Culture was a priority; relatives arranged tours of the private art collections of John S. Phillips (1800-76) and Henry C. Gibson (1830-91) and that were later donated to PAFA in 1876 and 1892, respectively.

Beaux’s art instruction began in the Walnut Street studio of Catherine Drinker (1841-1922), a distant relative and later the first part-time woman instructor at PAFA. She then continued in the school of Francis Adolf Van Der Wielen (active in Philadelphia 1870-74). By 1874 Beaux began teaching. Self-directed and ambitious, Beaux sought further professional training at PAFA from 1876 to 1878. She took antique, portrait, and costume classes there, but did not join Thomas Eakins’s notorious figure painting classes. In her autobiography she explained her resistance to the magnetic Eakins: “A curious instinct of self-preservation kept me outside the magic circle.” Instead she turned to Eakins’s less-controversial protégé, William Sartain (1843-1924), for instruction in painting the live model. In the midst of her academic training, she produced fossil drawings on commission from the U.S. Geological Survey (1877–79). After just one month at Piton’s Art School (1879), she obtained commissions for children’s portraits on china, much in vogue at the time. That same year she began her lifelong practice of exhibiting portraits at PAFA.

Family and Friends

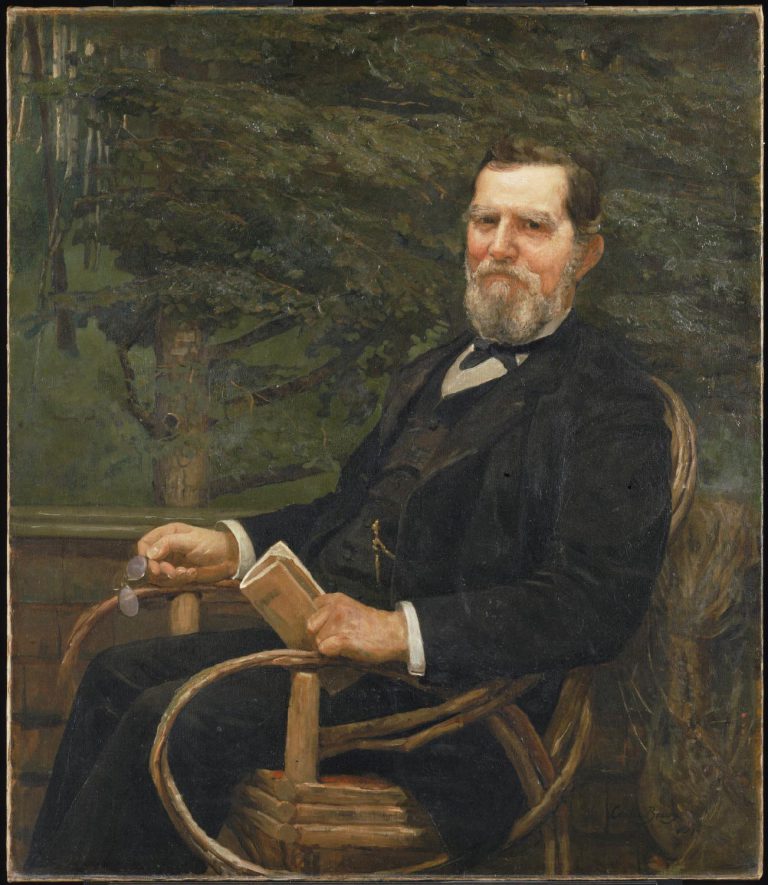

Throughout her career, Philadelphia family and friends were essential to Beaux’s evolution as a portraitist. Her first major essay in oil was The Last Days of Infancy (1883-84), a double portrait of her sister Ernesta Beaux Drinker (1852-1939) and her nephew Henry S. Drinker Jr. (1880-1965). Beaux layered the informal scene with psychological and emotional overtones that transcended the formal influences of James A.M. Whistler (1834-1903) and Sartain. Exhibited to critical acclaim in New York, Philadelphia, and Paris, it won the academy’s Mary Smith Prize for the best work by a local woman artist. This distinction launched her career locally where there was a constant demand for portraiture, a Philadelphia tradition among old wealth, civic organizations, and the aspiring commercial class. Though not raised in a wealthy household, Beaux identified herself and was identified with the well-bred, cultured, and moneyed elite, who were interconnected through clubs, church, marriages, and business. In quick succession she painted the Reverends Chauncey Giles (1813-93) and William Henry Furness (1802-96); businessmen George Burnham (1817-1912), George M. Troutman (1811-1901), and Frances Drexel Paul (1852-92); and lawyer John Cadwalader (1843-1925). Illustrious families, anxious to extend their legacy, also commissioned portraits of their children.

Beaux went to study in the ateliers of Paris and on the coast of France from 1888 to 1889, widening her repertoire and techniques and absorbing new ways of seeing color and light while working en plein air. On a visit to Cambridge, England, she reunited with an old Philadelphia friend, Maud DuPuy Darwin (1861-1947), whose connections led to a few commissions, enhancing the artist’s recognition abroad. Though there were viable options for continued professional success in Europe, Beaux returned to Philadelphia in 1889. During the next decade her portrait practice thrived. In her best oeuvre from that period there was an intricate mix of precise craftsmanship, up-to-the-moment style, and a feeling of spiritual kinship with her sitter, as in Sita and Sarita, 1893 (Sarah A. Leavitt (1868-1930). With increased confidence she traveled and exhibited in New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Paris, and Boston, winning numerous prizes and medals. In Philadelphia she garnered three more Smith Prizes, the Gold Medal of Honor at PAFA, and a gold medal from the Art Club of Philadelphia. One of her most lauded paintings of Philadelphia’s Quaker upper crust was Mother and Daughter, 1898, a portrait of Mrs. Clement A. Griscom (1840-1923) and Frances Canby Griscom (1879-1973). Beaux created a dramatic statement of expectation and pride in partaking of certain social and cultural rituals, to which she added focused lighting and dazzling brushwork.

In 1895 Beaux began to teach portraiture at PAFA, becoming the school’s first full-time woman instructor and confirming her importance in the city’s art world. She established a winter studio apartment in New York and built a summer studio home in Gloucester, Massachusetts, from which her social and professional spheres expanded immeasurably. She never severed her ties to Philadelphia, family, and PAFA, where she continued to teach until 1915, and was in constant demand as a juror at the annual exhibitions. One of her staunchest advocates was Harrison Morris (1856-1948), managing director of PAFA from 1892 to 1905, who helped her maintain her status as Philadelphia’s preeminent portraitist.

Distinguished Sitters

After the turn of the century, Beaux’s sitters included a distinguished array of international figures such as President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) and French Premier Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929), yet she took equal delight in painting local acquaintances and family, especially her niece Ernesta (Aimee Ernesta Drinker Barlow, 1892-1981). Beaux’s feminist alliance with independent career women was conveyed through the serious demeanor seen in portraits of local activists Eliza Sproat Turner (1826-1903) and Marion Reilly (1897-1928), dean of Bryn Mawr College.

Beaux’s prolific painting career was curtailed by a fall in 1924. Unbreakable in spirit and energy, she penned her autobiography Background with Figures, in which fond reminiscences indicate that Philadelphia remained the emotional root of her multi-blossomed life. Considered by many “the greatest woman painter alive,” she was often compared to John Singer Sargent, the leading society portraitist. Her reputation far exceeded her phenomenal local success; she was named by Good Housekeeping “one of America’s most distinguished living women,” and she served the international community as an artistic ambassador.

Cynthia Haveson Veloric, M.A., is a research assistant in the American Art Department at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. She has recently published articles on Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Alexander Stirling Calder, Hutchings California Magazine, and Martin Johnson Heade. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Background With Figures: Autobiography of Cecilia Beaux (Archive.org)

- Cecilia Beaux (National Museum of Women in the Arts)

- Portrait of Cecilia Beaux (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts)

- The Last Days of Infancy (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts)

- Mother and Daughter (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts)

- Ernesta (Child With Nurse) (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

- Sita and Sarita (National Gallery of Art)

- Portrait of George Clemenceau (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

- Oil Painting: Cecilia Beaux's Legacy (Artist Daily)

- Cecilia Beaux Forum (Portrait Society of America)

- Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Cecilia Beaux (Theodore Roosevelt Center at Dickinson State University)