Byberry (Philadelphia State Hospital)

Essay

From the arrival of its first patients in 1911 to 1990, when the Commonwealth formally closed it down, the Philadelphia State Hospital, popularly known as Byberry, was the home for thousands of mental patients.

In its early decades Byberry was controlled by the city, and from 1938 onward it was one of the several hundred state hospitals that were the core of American mental health care. Many of those hospitals were “noble charities,” some of the earliest having opened at the urging of the humanitarian reformer Dorothea Dix, who sought to move the “insane” poor out of jails and prisons. Following the therapeutic theories of the day, the asylums (later renamed state hospitals) offered rural retreats from the growing cities and at least the promise of treatment.

Unlike most of those hospitals, Byberry was opened as a city institution in Northeast Philadelphia to relieve overcrowding at Blockley, a huge institution in West Philadelphia that held the indigent insane in what one observer called “an ancient monasterial structure” as well as many varieties of the poor and homeless. In 1911, overcrowding in the “insane department” (also known as the Philadelphia Hospital for the Insane) led to the transfer of some inmates to Byberry City Farms (the city’s poor farm). Two years later, admissions of the insane to Blockley ended, and Byberry provided shelter and custodial care, usually at the most minimal levels and with considerable overcrowding. By 1914, Byberry held 2,267 residents, by far the largest of Pennsylvania’s twenty-one county mental institutions and larger than seven of its eight state hospitals. After a series of scandals across the state, in 1938 the Commonwealth took over Byberry and several other city institutions and renamed them state hospitals.

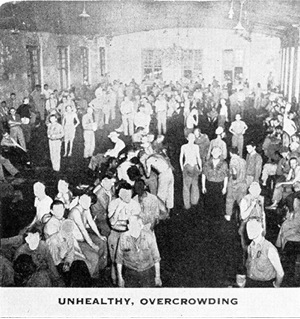

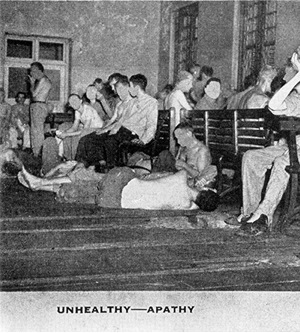

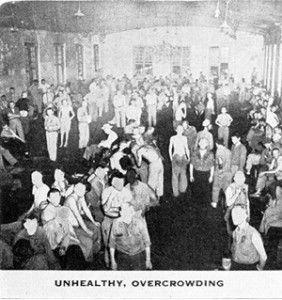

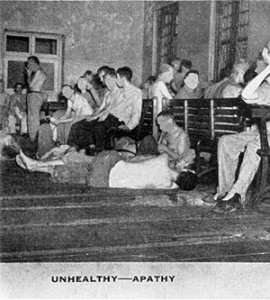

But renaming a huge overcrowded custodial institution a “hospital” simply heightened the gap between humanitarian intention and custodial reality. While some of the newly admitted were offered more active care, many inmates became “institutionalized” into a unique community experience, with tedium relieved by work crew duties, sitting in day rooms, or wandering around the grounds. Scandals of abuse and neglect were common. Overcrowding was a constant problem: a 1934 national survey of institutional care of the mentally ill reported that Byberry had over 4,500 inmates, while its rated capacity was 2,500. In contrast, Friends Hospital, a private institution, held 155 patients, less than its rated capacity of 190, and private sanitoria such as Fairmount Farm had even fewer (twenty-two residents, with a rated capacity of forty-four).

Despair About Mental Illness

The meager city or state support, the absence of affordable alternative care in the community, and a deepening public and even professional despair about mental illness completed the transformation of Byberry into what University of Pennsylvania sociologist Erving Goffman termed a “total institution.”

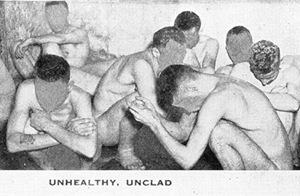

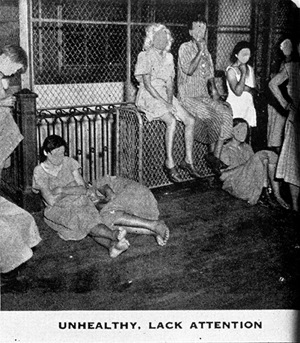

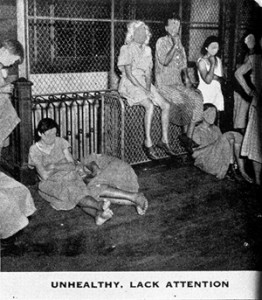

Conscientious objectors performing alternative service during World War II witnessed and even surreptitiously photographed scenes of everyday neglect and even brutality that shocked them, though these conditions were well known to city and state officials. Novels and films like The Snake Pit and photographs in national magazines like Life and PM reached a broader public with the message that basic living conditions in the state hospitals were very poor. Byberry was among the worst in Pennsylvania.

The most damning indictment of the failures of Byberry and similar institutions appeared in the work of pioneering journalist and reformer Albert Q. Deutsch in his 1948 book, The Shame of the States. Byberry was “Philadelphia’s Bedlam,” the equal of the notorious London home for the mad in the previous century or in Deutsch’s words akin to Nazi concentration camps.

Deutsch’s account included stunning photographs of such scenes as the “male incontinent ward,” and documented the saddest and most terrifying parts of the huge institution. Other photographs of the era, including a 1946 report by the Pennsylvania Department of Welfare, showed similar scenes. Regardless of the public reaction, the absence of alternatives meant Byberry continued to grow. By 1947, the institution held 6,100 patients, with an average yearly cost per patient of $346.

Soon after the national census of state hospitals peaked in the mid-1950s, a series of changes began the era of deinstitutionalization. But the scandals at Byberry continued: unexpected patient deaths, mistreatment, and extensive use of seclusion and restraint. Lawsuits successfully challenged the image of an effective mental health facility and pressed the state for change.

Closing of Byberry

By the late 1980s, Byberry was regarded as a “clinical and management nightmare,” despite the fact that its census had fallen to about 500 by 1987. In that year, Pennsylvania Governor Robert Casey directed that it be closed. Shutting Byberry led to the “unbundling” of psychiatric care for the seriously mentally ill, replacing the specialized community experience of a total institution with community programs provided by private non-profit agencies.

After the last residents left the huge campus, the physical plant of more than fifty buildings continued to decline. Byberry became a favorite visiting place for urban adventurers who wandered its structures and scavengers who stripped away copper and wiring. Eventually a plan to reuse the site led to demolition of almost all of its buildings in 2006 and construction of offices and housing (“Arbours at Eagle Pointe”).

But Byberry lived on in memory: Websites, rich with historical photographs and other documents, commemorated and even celebrated its notorious past.

George W. Dowdall is Professor Emeritus of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University and Adjunct Fellow, Center for Public Health Initiatives, University of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Philadelphia State Hospital (Asylum Projects)

- Blockley Almshouse (Asylum Projects)

- Philadelphia State Hospital, Byberry (Opacity)

- WWII Pacifists Exposed Mental Ward Horrors (All Things Considered, NPR)

- Blockley days; memories and impressions of a resident physician, 1883-1884 (Hathi Trust Digital Library)