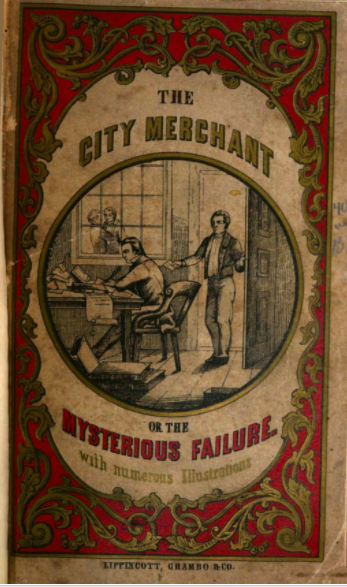

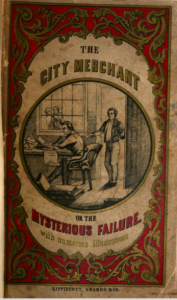

City Merchant (The); or, The Mysterious Failure

By Susan Barile

Essay

The novel The City Merchant; or, The Mysterious Failure, written by John Beauchamp Jones (1810-66), captures the height of Philadelphia’s anti-abolitionist movement and its emotional force and toll on the city, while at the same time transcending its locale to comment on the dynamics of market capitalism in early nineteenth-century America.

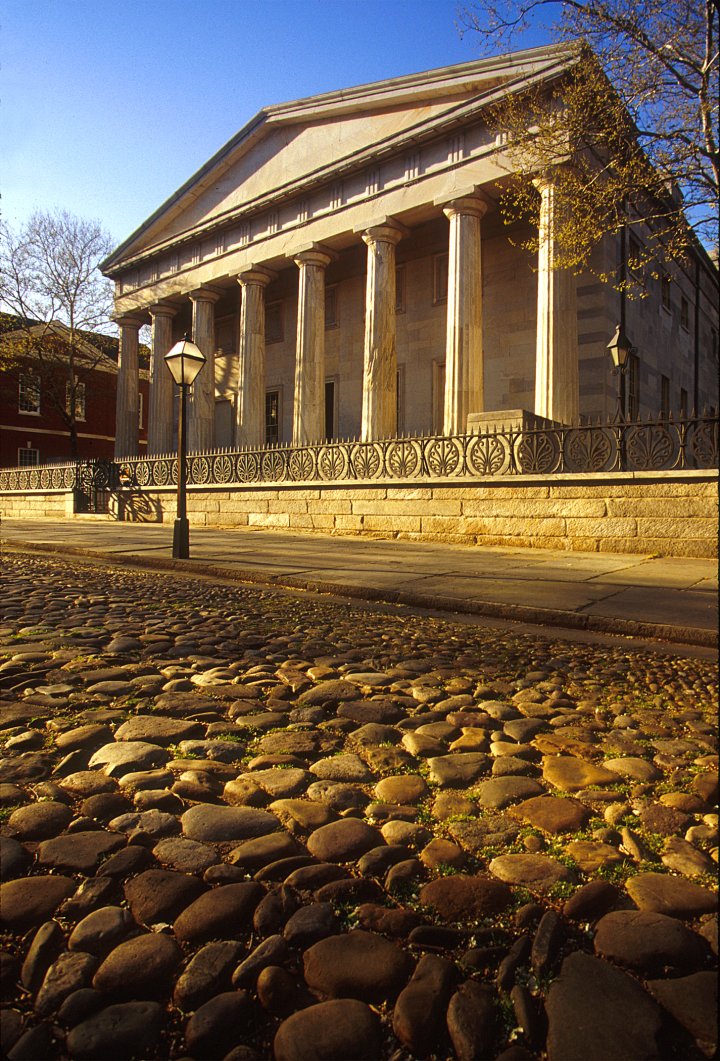

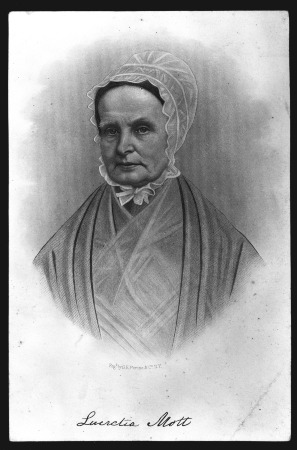

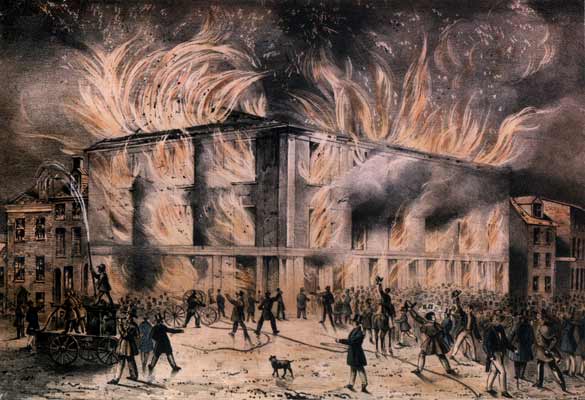

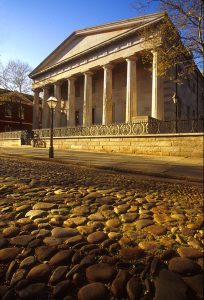

The City Merchant chronicles the rising fortunes of a third-generation Philadelphia merchant, Edgar Saxon, whose father and grandfather failed in business. Although Saxon’s father recognized commercial trends too late to help himself, he left a diary for his son that described how the capitalist economic system rose and fell in cycles, thus enabling Edgar to find great opportunities during times of bust. In addition to the novel’s economic concerns, the plot also reveals Beauchamp Jones’ anti-abolitionist position, using social conditions and rising violence in Philadelphia as a backdrop to the growing mercantile apprehensions on Market and Front Streets. Although he plays with chronology, real events are depicted in the novel, including the destruction of Philadelphia’s abolitionist meeting hall, Pennsylvania Hall; the financial panic of 1837; Andrew Jackson’s veto of the congressional rechartering of the Bank of the United States; and the Philadelphia riots of 1838 and 1842. Historical figures also appear, including Lucretia Mott (1793-1880) and Frederick Douglass (1818-95).

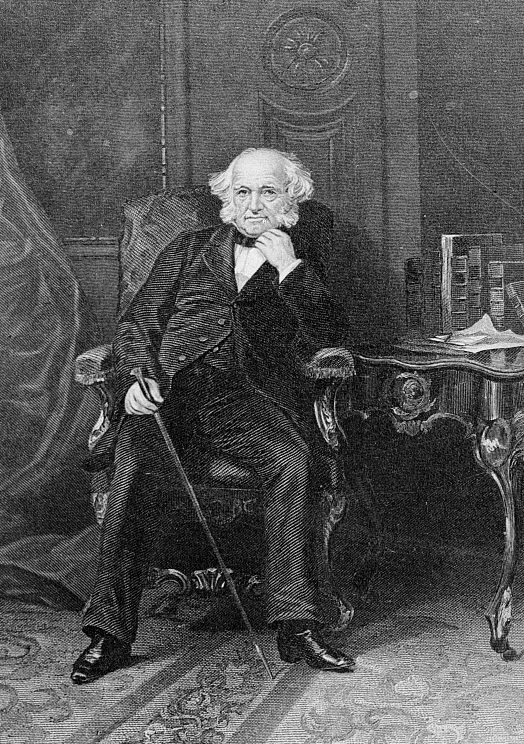

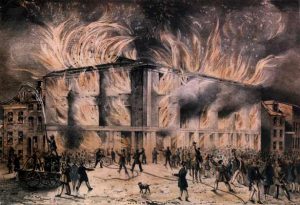

The novel begins on Market Street in 1836 in Philadelphia’s thriving commercial marketplace. The first half is primarily concerned with Saxon and his decision to sell his stocks of various holdings. He tells Nicholas Biddle of the Bank of the United States (who was indeed president of the Bank of the United States headquartered in Philadelphia) that he is doing this in order to “secure his wealth against the possibility of serious diminution” that will be the result of the excesses of his fellow businessmen’s financial speculations assuming, as Saxon does, that Martin Van Buren will be elected president of the United States. Rumors then circulate that Saxon’s business is failing. Beauchamp Jones dramatizes the link between the excess of speculation and the politics of race during the second half of the novel, which builds up to and depicts the burning of Pennsylvania Hall on the evening of May 17, 1838.

Beauchamp Jones believed that Northern politicians, or “white instigators,” undercut the power of the Southern states by advocating, through agitation and riot, the end of slavery. He alleged that abolitionists deliberately provoked violence through public displays of interracial contact. The second half of the novel follows several lines of development. The author employs the sensational plot contrivance of depicting the kidnapping of Saxon’s nieces by mulatto men. The two men are cousins of Olivia, who was once a slave and is now “passing,” yet is unhappy with her lot in the North. Saxon’s porter, Paddy Cork, is exploited by Democrats in his facilitation of the burning of the hall and leaves the party, coming to the realization that “party business [is where] a man must demean himself to do all sorts of nasty tricks for a little bit of office.”

A day in the country, minor love subplots, and a hypocritical pastor are additional components in the story of Edgar Saxon, who ultimately enjoys even greater financial success, while his fellow merchants, who erroneously relied on the market, lose their fortunes. A disturbing coda depicts a wealthy Philadelphia abolitionist hosting a party for African Americans on Chestnut Street. Her guests seemingly do not know how to behave, her Black staff refuses to serve them, and her white servant girls quit. The hostess, Miss Lofts, ends up personally attending to her guests and comes to the conclusion that “it would be best to be a philanthropist only in theory.”

Author, journalist, diarist, and southern Civil War clerk Beauchamp Jones was born in Baltimore. Raised in Kentucky and Missouri, he lived in or near Philadelphia during several years of his adult life (particularly 1839-40, 1845, 1847-48 and, 1857-61). He shared a brief correspondence with Edgar Allan Poe (1809-49) in the summer of 1839. The City Merchant; or The Mysterious Failure, published in 1851 by Philadelphia publisher Lippincott, Grambo & Co., was Beauchamp Jones’s third novel, but the first published under his name. His first, Wild Western Scenes (1841), sold over 100,000 copies and was followed by The Western Merchant: A Narrative Containing Useful Instruction for the Western Man of Business (1849). Both were published under the pseudonym Luke Shortfield. In 1857, Beauchamp Jones founded a Philadelphia weekly, The Southern Monitor, which he edited during its three years in press. According to the Dictionary of Missouri Biography, the newspaper “helped to fuel the growing sectional crisis.” His final work, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary, for which he is mostly remembered, records his time as a clerk in Richmond’s Confederate War Office. Beauchamp Jones believed in the Union, but was sympathetic to the South. The diary, published in 1866, reveals his growing disillusionment with Jefferson Davis and is considered one of the finest civilian accounts on the conditions of the Confederacy. After the war, John Beauchamp Jones returned to the North, where he died in Burlington, New Jersey.

Susan Barile is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Hunter College, New York, in the Department of English, and a graduate of The Graduate Center, New York, where she edited the letters of Edith Wharton to Bernard Berenson in fulfillment of her Ph.D. She is also the author of The Bookworm’s Big Apple: A Guide to the Booksellers of Manhattan (Columbia University Press, 1994). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Pennsylvania Hall Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- The City Merchant; or, The Mysterious Failure (Google Books)

- J.B. Lippincott Publishing (PDF, Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Pennsylvania Abolition Society — A Place for the “Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage” (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The Wedding that Ignited Philadelphia (PhillyHistory Blog)