Civil Rights (Persons With Disabilities)

By Charlene Mires | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Philadelphia-area people with disabilities and their allies joined the nationwide escalation of activism for civil rights during the second half of the twentieth century. Their protests and legal actions forced substandard institutions to close and liberate their residents. They also held local authorities accountable for implementing landmark federal legislation to improve accessibility, especially on public transportation, and to secure equal opportunity for work and education. Into the twenty-first century, individuals with disabilities and their allies remained vigilant to prevent the erosion of hard-won victories.

The disability rights movement of the twentieth century challenged decades of social and legal restrictions placed on persons with disabilities by states and localities. During the nineteenth century, these included barring people perceived as impaired from casting ballots; New Jersey and Delaware were among the states whose early constitutions banned any “idiot or insane person” from voting. Almshouses, asylums, hospitals, and other institutions confined many physically and mentally disabled people, effectively incarcerating them for life. Across the nation, cities enacted ordinances later known as “ugly laws” to outlaw people considered “deformed” from being seen in public. By the late nineteenth century, the pseudo-science of eugenics sought to prevent future generations of “defectives” through laws to ban marriages and require sterilizations, including statutes enacted in New Jersey and Delaware (but not Pennsylvania).

The disability rights movement emerged from a combination of factors in the decades following World War II. Wounded veterans from two world wars, together with survivors of recent epidemics of polio, expanded the population of people with disabilities who needed public and private support. Meanwhile, the emphasis on individual freedom and human rights voiced by the federal government during the war and subsequently by the United Nations provided a vocabulary for pursuing civil rights on many fronts. People with disabilities, their families, and allies embraced this framework and embarked on strategies similar to those deployed by African Americans, women, and other groups seeking their full rights as citizens. Activists in the preceding movements at times worked in tandem with the quest for disability rights.

Parents Advocate and Organize

Parents of children with disabilities were among the earliest to organize to advocate for equal access to education and quality of care in residential treatment facilities. Local chapters of national organizations focusing on specific conditions, such as cerebral palsy, formed throughout the Greater Philadelphia region to raise awareness and funding. During the 1950s, a time of idealization of family life, parents called attention to disability as an experience that could affect any family. Author Pearl S. Buck (1892-1973), living in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, encouraged parents across the nation to share their stories when she published The Child Who Never Grew (1950) about seeking care for her daughter, Carol, at the Training School at Vineland, New Jersey. Buck later chaired the Governor’s Committee on Handicapped Children formed in Pennsylvania in 1958. Parental concern led another Pennsylvania governor, Richard L. Thornburgh (1932-2020), to become an early advocate for disability rights after one of his sons suffered a brain injury. Later, as U.S. attorney general, Thornburgh helped secure passage of the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act.

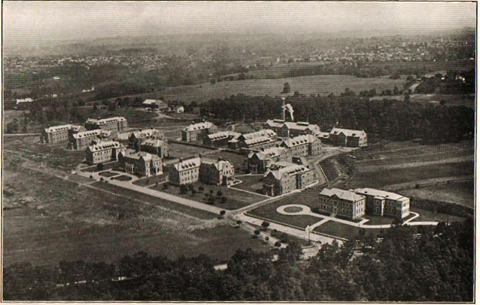

Parent advocacy groups based in Philadelphia included the Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Children (PARC), organized in 1949. A member of PARC triggered a chain of events with national implications in 1968 by encouraging local television reporter Bill Baldini (b. 1943) to expose horrendous conditions at the Pennhurst State School and Hospital in Chester County, Pennsylvania. A subsequent class-action lawsuit, PARC vs. Pennsylvania, resulted in a consent decree ordering the state to provide access to free public education to “retarded” children. The case, argued by the Public Interest Law Center of Philadelphia, provoked similar lawsuits that culminated with the federal Education for All Handicapped Children Act, passed in 1975.

Years of additional litigation on behalf of Pennhurst residents, including Halderman v. Pennhurst (filed 1974) and Youngberg v. Romeo (filed 1976), culminated with closing the institution in 1987. Other institutions across the nation shut down as the Public Interest Law Center trained attorneys in other states to apply their strategies. In 2002 the Law Center filed a class-action in Delaware that led to a settlement for greater access to community services for people with developmental disabilities housed in the Stockley Center in Sussex County. Individuals with developmental disabilities also organized to speak on their own behalf with the group Speaking For Ourselves, which originated in Montgomery County in 1982 and expanded with chapters elsewhere in the region.

Lawsuits Multiply

Legal actions continued to press for equal opportunity in education. For example, the 1993 case Oberti v. Board of Education of the Borough of Clementon (New Jersey), secured classroom support for a student with Down syndrome. In Pennsylvania, the class action Gaskin v. Commonwealth in 1994 called attention to needs for greater compliance with the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

In pursuit of accessibility and independent living, adults with disabilities mobilized from the 1960s through the end of the century to insist that federal laws such as the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 were fully implemented. In Philadelphia and South Jersey, activists pressed SEPTA (the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority) and PATCO (the Port Authority Transit Corporation) to make trains, buses, and subways fully accessible. In Philadelphia, the long campaign of attending meetings, staging protests, and filing lawsuits was led by the Pennsylvania chapter of Disabled in Action, an advocacy group founded in New York in 1970 by Philadelphia-born Judith E. Heumann (1947-2023). A survivor of childhood polio and wheelchair user, raised in Brooklyn, Heumann waged a highly publicized and successful battle to gain a teaching license in New York City. She remained a prominent leader of the disability rights movement throughout her life, including an appointment as assistant secretary of the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services at the U.S. Department of Education during the Clinton administration.

Philadelphia attorney Stephen F. Gold (b. 1942) represented individuals, Disabled in Action, and the organization known as ADAPT (American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit) in lawsuits over accessibility and equal opportunity. A New York-based group founded by veterans with spinal cord injuries, the Eastern Paralyzed Veterans Association, included Philadelphia and South Jersey in a series of 1988 lawsuits to secure greater elevator access to subway stations. The organization prevailed in seeking installation of an elevator in the transportation center then under construction in downtown Camden, where the PATCO Speedline ran underground. Similarly, the U.S. District Court found that SEPTA discriminated against persons with disabilities by failing to comply with federal laws and regulations when renovating subway facilities.

Following passage of the federal Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Disabled in Action and twelve individuals with disabilities filed a lawsuit in 1992 to require the City of Philadelphia to install curb ramps (curb cuts) as part of any street resurfacing project. The successful suit, argued by Gold, set a precedent for other cities across the country. Curb ramps remained a decades-long issue in Philadelphia, leading to another lawsuit by Disabled in Action and others in 2019. The resulting settlement agreement, approved in 2023, ordered the City of Philadelphia to install or repair at least ten thousand curb cuts over the next fifteen years.

The disability rights movement in Greater Philadelphia unfolded through the efforts of multiple organizations and individuals, often setting nationally significant precedents. Throughout the region, vigilance by local activists remained necessary into the twenty-first century to secure and expand the civil rights of persons with disabilities.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and Editor-in-Chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2023, Rutgers University.