Civil War Museum of Philadelphia

Essay

Founded in 1888 by veteran officers of the Civil War, the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia was a monument to those who fought to preserve the United States in the face of rebellion. Originally known as the War Library and Museum, the institution operated in several sites in Philadelphia before settling in a townhouse near Rittenhouse Square from 1922 until 2008, when it closed for financial reasons. In 2016, the museum transferred its three-dimensional collections to the Gettysburg Foundation with artifacts also displayed at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia. In their new homes, artifacts originally treated as memorial relics—including items from General Ulysses S. Grant (1822-85), Abraham Lincoln (1809-65), and lesser-known soldiers and officers—were reinvented in the context of modern exhibits about such topics as slavery, racism, and the broader causes and consequences of the Civil War.

The creation of a Civil War museum in Philadelphia originated with the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), a fraternal association for veteran officers of the Civil War founded in 1865 at the Union League in Philadelphia. The group formed in the wake of the assassination of Lincoln amid fear of a continuation of the Civil War, but when that fear subsided, commemoration became central to the association’s mission. The chartering of the War Library and Museum in 1888 reflected new efforts at remembrance that occurred in part because veterans were aging, but also because in the wake of Reconstruction, the Civil War seemed resolved and so it began to fade from current events into history.

Members of MOLLUS, including John Page Nicholson (1842-1922), who had taken control and revived the organization a decade earlier, chartered the War Library and Museum to collect, preserve, and maintain books and artifacts—“implements, relics, and muniments of war”—pertaining to the “War of the Rebellion.” The library and museum reflected a larger interest in documenting the memories of aging US Army and Navy veterans so as to capture history before it was lost. The urge to collect artifacts from veterans and to write and publish their recollections was also part of a contest over who would get to write the history of the Civil War.

Donations From Veterans

Collections grew throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, primarily from the donations of veterans and MOLLUS members, but the early history of the War Library and Museum revolved mostly around finding a home for itself. The State of Pennsylvania offered $50,000 for construction of a building if MOLLUS could raise $100,000 more. Throughout the 1890s, the group wrote appeals, pursued various locations, and drew up designs for a grand structure that would house offices, banquet halls, and the library and museum. The veterans envisioned a repository of history and material objects, but also a space where they could socialize and reminisce.

At different times, MOLLUS pursued homes in council chambers at Independence Hall, in properties near City Hall, and in a building on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, but none of these proved feasible. In 1907, the organization rented rooms in the Flanders Building at Fifteenth and Walnut Streets, and in 1922 it made a permanent home in a townhouse at 1805 Pine Street. The selection of a more modest home was a disappointment, but it enabled building funds to sustain the institution as an endowment for much of the twentieth century.

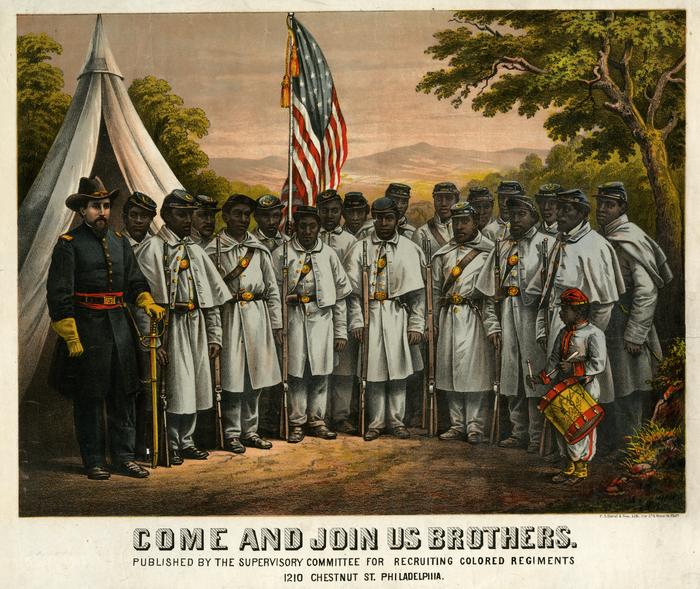

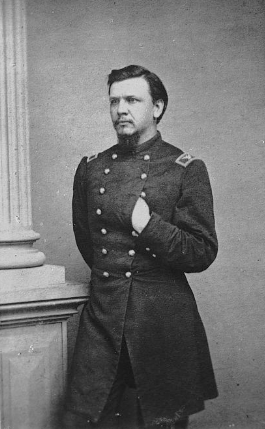

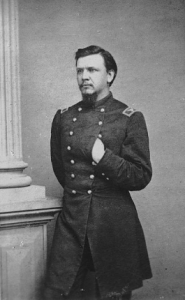

At the Flanders Building, for the first time, exhibits showcased the collections publicly. The displays included the Tiffany sword and scabbard that General Ulysses S. Grant received after the battle at Vicksburg, a uniform worn by General George Meade (1815-72) at Gettysburg, and casts of Lincoln’s face and hands made by sculptor Leonard Wells Volk (1828-95) just before the war broke out. Visitors could also see the cane Lincoln carried into Ford’s Theater, a tree trunk hit by a cannon ball at Gettysburg, a recruitment drum played outside enlistment headquarters in Philadelphia in 1861, and the paisley smoking jacket worn by Jefferson Davis when he was captured by Union soldiers in 1865.

Ephemeral items and other personal relics donated by Union veterans contrasted strikingly with other Civil War commemorations in Philadelphia at the time, including the equestrian statues of Meade and General John Reynolds (1820-63) and the Smith Memorial Arch in Fairmount Park. While Nicholson and MOLLUS wanted the library and museum to be similarly monumental, the museum’s collection was a mixture of official military history documented by the uniforms and firearms of commanding officers and a more subtle memory of the Civil War driven by everyday artifacts donated by individuals (albeit mostly officers) that revealed alternative, more personal histories. General Lewis Merrill (1834-96), a member of the museum’s Board of Governors, explained that an institution like theirs “will be a more lasting monument than any one that is built of stone or metal, and will be more influential in telling the truth of history and doing justice to its defender.”

From Private to Public

Debates arose in the 1920s over whether the collection needed to be better interpreted now that veterans (who could recall their own experiences) were dying and MOLLUS membership was passing to descendants, but a catalog to guide visits never emerged. In the members-only museum, the artifacts were largely left to speak for themselves and the library and archives, while available for use, were only partially cataloged or cared for.

MOLLUS remained involved with the museum until the 1970s, when the organization and the museum separated so that each could dedicate more resources to its narrower mission. In 1976, coinciding with the Bicentennial, the museum opened to the public on a day-to-day basis, and in the 1980s special exhibits began to interpret more diverse histories—including those of women or African Americans or even the rebel states—in addition to the other long-standing displays of the collections.

By the early 2000s, a dwindling endowment and declining visitation threatened the sustainability of the museum. Legal proceedings against former curator Russell Pritchard Jr. (b. 1940) and his son for fraud and theft from a variety of Civil War institutions, including the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia, provided further evidence of the museum’s longtime mismanagement. One proposed solution to address the state of the museum would have loaned part of the collection to a planned Civil War Museum in Richmond, Virginia. The backlash in Philadelphia against that idea resulted in a proposal to create a Center for Civil War Studies based at the Union League that would have included partners like the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, and the Philadelphia Historical and Museum Commission. The desire, beyond creating an exceptional network of research collections, was to make Philadelphia a destination not just for Revolutionary War tourism, but also for tourism around nineteenth-century history and the Civil War. Plans for such a consortium never came to fruition, nor did another plan for the museum to occupy Memorial Hall in Fairmount Park. Continuing the disappointments, in 2002 the State of Pennsylvania pledged $15 million toward a new facility but retracted the funds in 2009 during the recession.

A Dual Emphasis Emerges

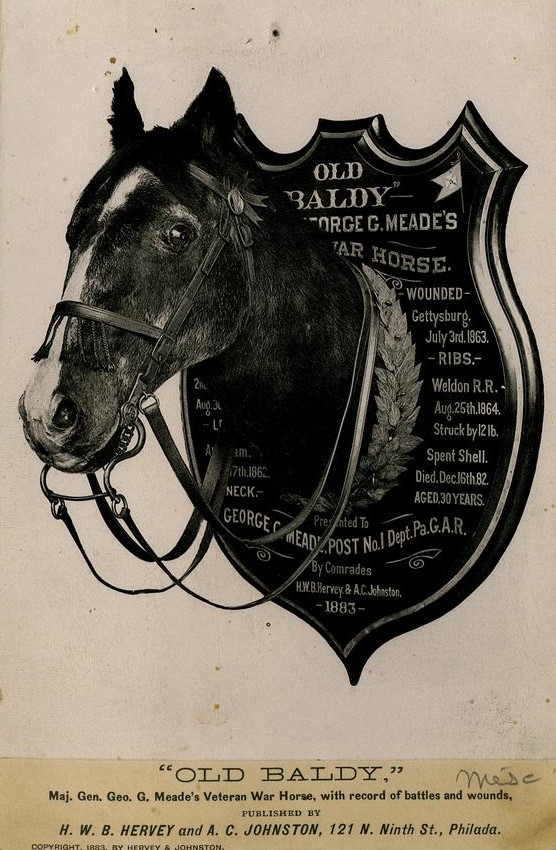

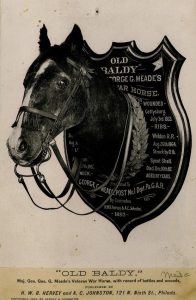

While the quest for a new home signaled a desire for a more professional, authoritative institution, appreciation also remained for the small, quirky museum on Pine Street that displayed, among other things, the preserved head of Old Baldy, General Meade’s horse. However, rather than develop either of these identities, in 2003 the institution reemerged as the Civil War and Underground Railroad Museum with a new dual emphasis that reflected trends toward more inclusive histories of the Civil War era. With a limited collection of African American materials, the museum turned to living history with actors portraying historical figures including Harriet Tubman (c. 1822-1913) and Absalom Jones (1746-1818). New outreach resulted in a 2006 program called “Faith and Freedom,” co-produced with Black churches. One program featured an actor portraying Jones giving his “Thanksgiving Sermon” at the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas.

In 2004, a grant from the William Penn Foundation enabled the first complete inventory of the collection, which revealed objects previously unknown to the museum or the nation. In addition to the already celebrated items from well-known figures, the inventory uncovered items like a pocket watch belonging to Brevet Capt. John O. Foering (1843-1933) that was dented by a bullet; a jar of peaches from an orchard on the battlefield of Winchester, Virginia; the tombstone of John Butcher (1845-99), a veteran of the United States Colored Troops; and an 1872 first edition of The Underground Railroad by William Still (1821-1902).

However, none of these developments could save the museum, which closed in 2008. An effort to work with the National Park Service to renovate the Second Bank in Old City to yield a usable space also failed, and ultimately in 2016 the artifact collections transferred to the Gettysburg Foundation—the private, nonprofit partner of Gettysburg National Military Park—with the promise that the National Constitution Center would still display some of the artifacts in Philadelphia. The museum retained the two-dimensional materials, including paintings, lithographs, and books that went on loan to the Union League and remained available to researchers there. Other artifacts—including the head of Old Baldy, which had been on loan from the Grand Army of the Republic Museum in Frankford—returned to the GAR Museum, which sustained Civil War memory in Philadelphia, although on a smaller scale.

In 2019, the National Constitution Center opened the exhibit “Civil War and Reconstruction: The Battle for Freedom and Equality,” which used Civil War Museum artifacts in an expansive history that explored the context, causes, and consequences of the Civil War. Extending to histories of injustice and violence, the exhibit encompassed causes like slavery and racism and consequences like the Reconstruction amendments to the U.S. Constitution and their simultaneous importance and impotence in the face of Jim Crow segregation. At the Gettysburg National Military Park Museum, meanwhile, artifacts from the Philadelphia museum illustrated the story of the Civil War from the perspectives of both the United States and the states that seceded. While the objects added authenticity in service of each institution’s interpretive goals, the new installations also demonstrated the contrast between the polished Civil War tourism of the twenty-first century and the earlier museum’s role as a nineteenth-century reliquary and evocative home for family legacies.

Ultimately, the Civil War Museum faced several hurdles that it could not overcome. By the late twentieth century, Philadelphia museums—especially small, lesser-known museums—were suffering financially. The Civil War Museum’s location was also challenging because Philadelphia never successfully cultivated a Civil War identity or Civil War tourism despite deep connections to that history. However, if, as a fundraising appeal from 1891 argued, the museum was meant to commemorate those “who gave their lives to the war which restored the Union and maintained the Constitution,” then the collections found a fitting final resting place at the National Constitution Center in an exhibit about the simultaneous successes and failures of that document and a more critical memory of the Civil War for a new generation.

Mabel Rosenheck is a writer, lecturer, and historian in Philadelphia. She works in the museum of the Wagner Free Institute of Science and teaches at Temple University in addition to freelance writing and research. She received her Ph.D. in Media and Cultural Studies from Northwestern University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University