Community Colleges

Essay

Two-year, public colleges—commonly known as community colleges—first appeared in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century. Situated at the intersection of secondary and higher education, they were local institutions that offered both general studies and vocational training. Referred to as junior colleges before the 1950s, they owed their inspiration to Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), whose idea for a “Publick Academy” in Philadelphia derived from his belief that education should be both academic and utilitarian. Franklin’s academy soon became the University of Pennsylvania, but its figurative descendant, the community college, did not become a fixture in the Greater Philadelphia area until the second half of the twentieth century.

Founded in 1901, Joliet Junior College in Illinois was the first two-year, public college serving a local community. It had more than eighty public and private counterparts across the country within two decades, most often in states with strong systems of public higher education. None were in the Greater Philadelphia area. The number skyrocketed over the next twenty years, however, reaching 456 by 1940 with combined enrollment approaching 150,000 students. About 18 percent of the nation’s undergraduates at that time studied in two-year institutions, almost two-thirds of them in public junior colleges. Despite such impressive growth, however, the two-year college struggled to carve out a distinctive place for itself in the American educational system. Was it an extension of high school, an introduction to college, or something else? Should its students expect to pass directly into the workplace upon graduation or continue their formal education?

In the 1930s most two-year colleges in the United States had no home of their own; public school districts provided them instructional and administrative space. In 1932 the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching recommended that the two-year college be recognized as the capstone of public education. But because the high school was well on its way to becoming a mass institution by then, some educators and policy makers thought that two-year, public institutions of post-secondary education deserved to have their own place in the American educational system. A special commission established by President Harry Truman (1884-1972) in 1946 endorsed this idea. Proposing that they be called community rather than junior colleges, the commission argued that they could help fight the Cold War by bringing higher education to a wide audience at the local level. But what should such institutions teach? Some favored general education for all, but most adopted a diversified curriculum for academic and social sorting and tracking.

1960s: The Rise of Community Colleges

There were almost no community colleges in Delaware, Pennsylvania, or New Jersey prior to 1960. A federal agency, the Emergency Relief Administration, funded six junior colleges in the Garden State in the 1930s, but just two remained after the agency terminated. Only a catastrophe like the Great Depression had justified any federal aid at all because most Americans thought education was a state and local obligation. A generation later these three states had many community colleges, including eight in the Greater Philadelphia area. Higher education was expanding thanks to the GI Bill, the Baby Boom, and the democratization of secondary education. The Community College of Philadelphia and Bucks County Community College opened in 1965; Montgomery County Community College in 1966; Camden County College, Gloucester County College, Delaware County Community College, and the Delaware Institute of Technology (soon renamed Delaware Technical Community College) in 1967; and Burlington County College in 1969.

State government helped these schools get established, but its ongoing role differed in each state. Enacted by the New Jersey legislature in 1962, the County College Act authorized the creation of public community colleges and set up procedures for launching them. It also committed the state to funding them, at least in part. Pennsylvania took a similar step one year later. The Pennsylvania Community College Act permitted local authorities to establish two-year colleges and called for developing master plans to coordinate their design and development. Adopted by the Delaware General Assembly in 1966, House Bill 529 authorized a statewide technical community college offering career, remedial, general, and transfer education. Congress undoubtedly gave all three states added incentive by adopting legislation in 1963 to fund construction of college facilities and, two years later, scholarships and loans to college students. Doing so did not preempt state control of higher education. Consequently, the management schemes worked out for community colleges in these three states reflected their different political cultures.

Small in population and in area, Delaware had a history by the 1960s of centralized educational decision-making. More than forty years before reformers had convinced the legislature to adopt a new public school code that greatly reduced the power of local authorities. The philanthropist Pierre Samuel du Pont (1870-1954) reinforced such thinking by giving more than $5 million to modernize the state’s public school buildings. The legislature’s decision to have one community college for the entire state followed from this history. The college might facilitate attendance and even tailor some programs to local audiences by having multiple campuses. Between 1967 and 1974 it opened four in Georgetown (1967), Dover (1972), Stanton (1973), and Wilmington (1974). But each campus was part of the same centrally managed institution.

Pennsylvania Rivalries and Local Control

In Pennsylvania regional rivalries and a strong tradition of local control delayed the adoption of a master plan for higher education until 1967. By then, the Commonwealth had fourteen community colleges, including four in the five-county Philadelphia area. Each had its own board of directors, and each reported to a local sponsor: a city (Community College of Philadelphia), a county (Montgomery County CC and Bucks County CC), or local school districts (Delaware County CC). Charged with implementing the Pennsylvania Community College Act, the newly created Council of Higher Education wanted to open more two-year colleges in the state, especially in areas it deemed underserved by public higher education. But there was some hesitation in Harrisburg because by 1960 Pennsylvania State University had fourteen two-year branch campuses, offering both terminal and transfer programs. It added five more between 1965 and 1967, one of which was in Delaware County. Other Pennsylvania universities such as Temple, Clarion, and the University of Pittsburgh had similar operations or aspirations. When Montgomery County CC offered to buy Temple’s suburban campus in Ambler, Temple said no, even though it had just sold the Stanley Elkins Tyler estate in Newtown to Bucks County CC. Already the site of the university’s horticulture program, the Ambler Campus was to be Temple’s portal in the suburbs after the university’s becoming state-related in 1965 put it on track for major expansion.

New Jersey’s approach to the oversight of community colleges vacillated between local control and centralized management. Adopted in 1967, the New Jersey Higher Education Act created a centralized administrative structure for overseeing and coordinating a state system of higher education. A new State Board of Higher Education and a Department of Higher Education now took responsibility for county college development; by 1982 they had helped raise the number of such schools from four to nineteen. But each school had its own board of trustees, most of whose members were appointed at the county level. Trenton never provided adequate funding, forcing these colleges to rely primarily on local property taxes and student tuition. They took more responsibility for themselves when the New Jersey Higher Education Restructuring Act (1994) abolished the State Board of Higher Education in a Republican move to reduce government regulation. Authorized by the state legislature in 1989, the New Jersey Council of County Colleges became the means by which these schools submitted a collective budget request to the state. In 2003 Governor James E. McGreevy (b. 1957) created by executive order the New Jersey Community College Compact, a partnership between the state and its county colleges. The compact’s primary goal was to strengthen training for workforce development, but it also sought to improve the protocols governing the transfer of county college students to four-year colleges and universities in New Jersey.

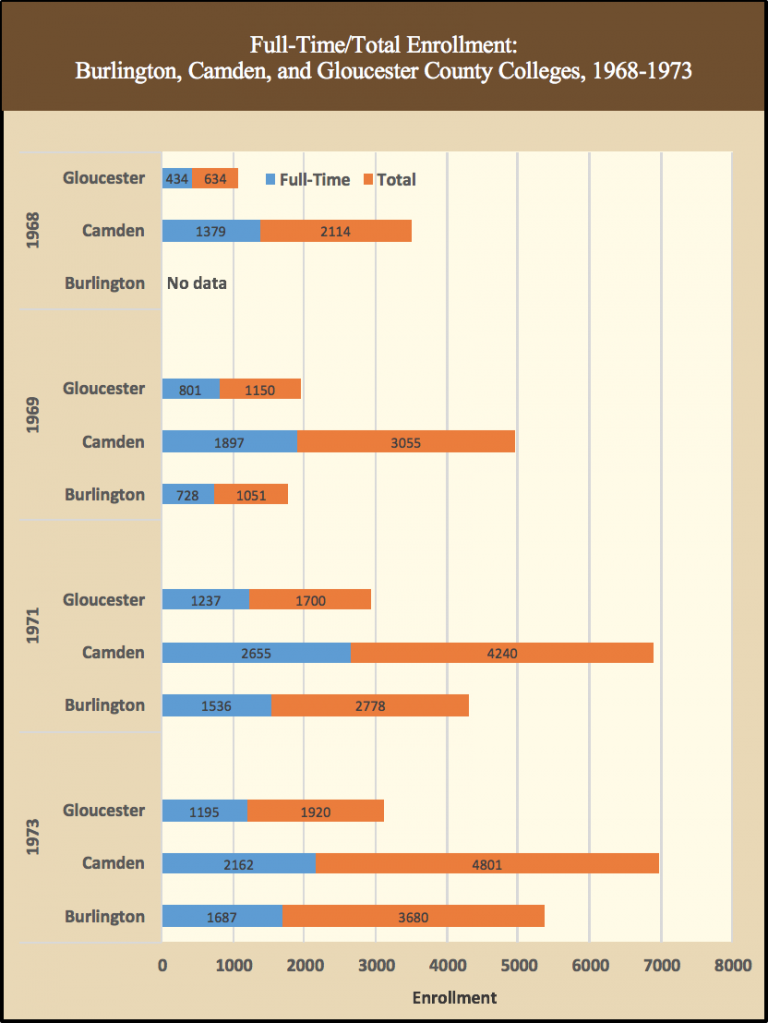

The community colleges in Greater Philadelphia grew rapidly at first. Enrollment at the Community College of Philadelphia reached 4,365 students in 1967, just its second year of operation. At Delaware County CC it popped by over 400 percent between 1967 and 1969. Bucks County CC went from 731 students in its first year to 5,607 in its seventh. In South Jersey the numbers were equally impressive.

Decades of Growth

Powered by an open-door admissions policy, the region’s community colleges continued to grow for the rest of the century. The Community College of Philadelphia became enormous, educating between 35,000 and 45,000 students annually. In its golden anniversary year (2007), Camden County College reported its enrollment to be more than thirty thousand, not counting remedial students. Enrollment also surged at the rest, bringing thousands of nontraditional students to campuses where they mingled with six to nine thousand degree and certificate candidates (matriculants). In 2016 the Community College Review reported that Montgomery County CC had 12,805 matriculants. According to the same source, the number of such students at the Community College of Philadelphia had reached 19,119, but Camden County College’s number had fallen from 14,471 to 12,051 since 2007. Full-timers now amounted to more than half the matriculants at only two of the eight schools in the region (Gloucester and Camden), reflecting a trend in undergraduate education that saw the time-to-degree ratio increase as more students, including many working adults, pursued higher education.

The campus facilities of the community colleges in Greater Philadelphia changed dramatically over the years, helping each of these schools develop their own brand and image. The Community College of Philadelphia conducted its first classes in a repurposed department store near City Hall. In 1973 it began migrating to its next location at Seventeenth and Spring Garden streets, an impressive neo-classical building that once had been the Philadelphia Mint, a move not completed for a decade. The community colleges in Burlington, Camden, and Gloucester Counties began their work in public schools but soon moved to their own facilities. Over time, every community college in the region erected buildings, often on large properties, and opened branch campuses. Purchased in 1967 from the Mother of Savior Seminary, Camden County College’s original campus in Blackwood came with 320 acres. In Camden city, it did not have a building of its own for twenty-two years. Partnering with Cherry Hill Township and the William G. Rohrer Foundation, it added a multipurpose campus on Route 70 and Springdale Road in 2000. Serving Delaware and Chester Counties, Delaware County CC eventually had six locations including one in Chester County Hospital.

The curriculum was never static at any of the region’s community colleges. As transfer institutions, they offered general education courses that could count toward bachelor’s degrees earned elsewhere. As adult institutions, they taught both credit and noncredit classes for academic advancement, professional development, or personal enrichment. As vocational institutions, they provided technical training that could lead to immediate employment. Their vocational programs responded to modifications in the local economy. Medical coding, information technology, hotel management, and culinary arts became popular choices as Greater Philadelphia left behind its industrial past for a future built on health care, communications, hospitality, education, and public administration. These applied curricula attracted many students, but even more popular were those for students aiming to transfer to four-year colleges or universities, including those not yet ready for college-level work. In 1973 the Office of Institutional Research at Bucks County CC did a comprehensive study of its recent graduates. It learned that the majority were still students one year after graduation and so was a plurality of all its graduates. Most had remained in the region, matriculating at Penn State, Temple, Trenton State (renamed the College of New Jersey in 1996), and West Chester. This pattern became more pronounced as the region’s four-year colleges and universities increased their tuition year after year. Looking for a cheaper alternative, many families decided to send their children to the local community college for their first two years. This helps to explain why the Office of Institutional Research at the Community College of Philadelphia found in 2013 that about 60 percent of its recent graduates had gone on to a baccalaureate program within five years.

Credit Transfer Not So Seamless

In theory, transferring from a community college to a four-year institution was seamless. Applicants for advanced standing at a four-year college or university expected to carry all their community college credits with them. But receiving schools did not always award full credit, leaving some transfer students with a deficit. Inter-institutional agreements to facilitate transfer were not new in the 1980s, especially in states with large, public higher education systems. Such agreements became increasingly important in the Philadelphia region, especially as undergraduate enrollments started to decline in the 1970s. To keep transfer students from going out of state, four-year colleges and universities in New Jersey and Pennsylvania adopted what came to be known as “articulation” agreements, often after lengthy negotiations with local and state authorities. In 1973 New Jersey adopted what it called the Full-Faith-and-Credit policy that promised a smooth transition between its county and state colleges. Graduates of approved transfer programs at county colleges were guaranteed admission to a state college with 68 credits, but in practice fewer than half had all their county college credits accepted. A state Higher Education Plan adopted in 1981 urged Rutgers, the state university, to implement the policy, but only its Camden and Newark campuses complied. The campus in New Brunswick demurred. By contrast, Temple signed separate articulation agreements with Bucks, Montgomery, and Delaware County CCs in 1998. In 2006 Pennsylvania required its fourteen state universities to admit graduates of the state’s community colleges and award them at least some transfer credit.

Transfer students almost always remained in the region. Rutgers-Camden was by the far the most popular transfer destination for students from the community colleges in Burlington, Camden, and Gloucester Counties. Between 1984 and 1986, only ten chose to enroll at Rutgers in New Brunswick. Temple University was the most popular destination for students from the Community College of Philadelphia. For example, more than one third of all the students transferring to Temple between 1988 and 1998 came from there, 7,662 out of 22,248. Both Temple and the Community College of Philadelphia closely monitored their transfer students’ five-year graduation rate, which went from 42.6 percent in 1988 to 49.3 percent six years later. But students from the Community College of Philadelphia never achieved a higher graduation rate than the university’s general population of transfer students.

In 2001 the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems concluded that Pennsylvania still had not developed “an effective system for providing community college services” across the state. It urged the existing schools to strengthen their capacities in workforce development and educational access. In response, some community colleges streamlined the transfer process by adopting dual admissions agreements. Over the next decade Montgomery County CC and Bucks County CC partnered with four state universities in Pennsylvania: Montgomery County CC with Cheyney (2005), Kutztown (2007), and West Chester (2009) and both Montgomery and Bucks County CCs with East Stroudsburg (2016). Montgomery County CC even reached such an agreement with Dickinson College, a selective, private institution more than one hundred miles from its main campus. In South Jersey both Gloucester and Burlington County College partnered with nearby Rowan University, leading both county colleges to change their name. Gloucester became Rowan College at Gloucester County in 2014 and Burlington became Rowan College at Burlington County the following year. By then the latter had guaranteed admissions agreements with more than thirty public and private colleges and universities.

Race and Economics

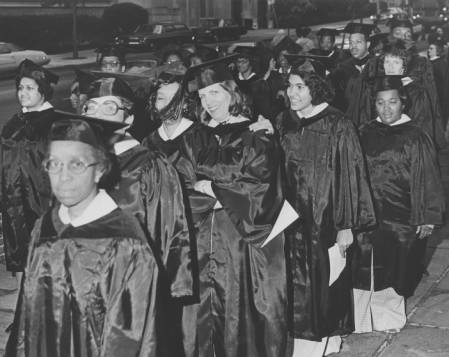

From their inception the community colleges in Greater Philadelphia enrolled far more white than Black students. The Community College of Philadelphia was the lone exception. By the turn of the millennium, after all, the city’s population was 44 percent African American. Philadelphia also had many champions of Black education. Led by Maurice B. Fagan (1910-92), the Philadelphia Fellowship Commission was one of the most important. Along with the NAACP, it urged city and state officials to establish a community college that would open the door to higher education for the city’s African Americans. From the beginning the Community College of Philadelphia attracted many Black students. In 1967 they comprised 23 percent of its student body. Fifty years later they were 40 percent.

Economic circumstances were also an important variable in the student demographics of the community colleges in the region. Their comparatively low tuition and work-friendly programs appealed to those with busy schedules and limited incomes. Such students often could not attend full time; the demands on their personal time and the opportunity costs of such attendance were too great. Many had spotty academic records. While these schools never enrolled only students from the lower half of the socioeconomic spectrum, such students increasingly predominated. Their alumni’s average annual earnings corroborate this generalization. In 2016 it did not exceed $40,000 for any of them. The suburban schools approached that number ($39,300 at Bucks and $39,200 at Montgomery), but the rest fell well below it, some by several thousand dollars ($32,800 at Delaware Technical Community College and $34,900 at the CC of Philadelphia).

When the community colleges in Greater Philadelphia appeared in the 1960s, there was no consensus about whether they were needed. It was not at all clear where they fit into the region’s educational system. Such uncertainty came from a lack of consensus about their status and mission. By the beginning of the twenty-first century the region’s community colleges had become an integral part of its educational system. They compensated for the limitations and failures of public education by providing trade training and remedial education. They broadened access to higher education by being a low-cost, local alternative for beginning college students. They contributed to economic growth and local pride by building modern facilities and operating multiples campuses. The complexity of this mission defied totally successful implementation, but it justified their repute as an educational staple in the region.

William W. Cutler III is Emeritus Professor of History at Temple University and the associate editor for education for The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University