Coronaviruses

Essay

Two major coronavirus epidemics in the early twenty-first century left their mark on the Greater Philadelphia region. The second of these epidemics, beginning in 2019, caused considerable loss of life; prompted major restrictions on education, social life, and the area’s economy; and exposed urban inequalities. Vaccine research undertaken in Philadelphia, however, played a critical role in limiting the death toll across the world.

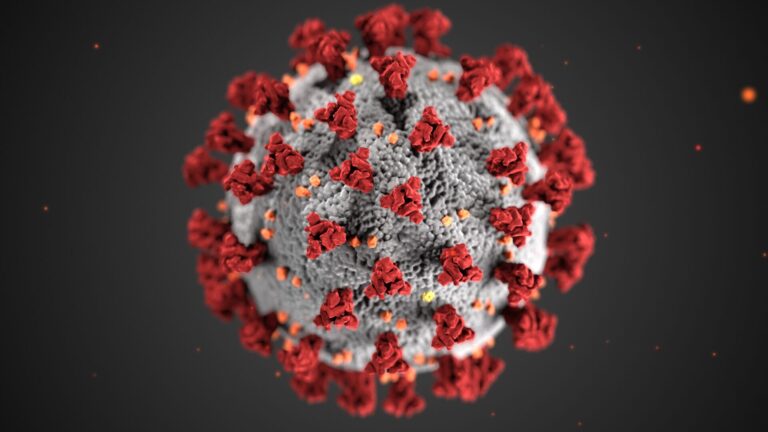

Coronaviruses, so-called because of their resemblance under a microscope to a crown, are a group of viruses that can infect a diverse array of mammals and birds, leading to an equally diverse array of symptoms and prognoses. The origin story of coronaviruses stretches back almost 300 million years, when the most recent common ancestor of all modern coronaviruses began to differentiate into distinct viruses. But only in the 1930s—just a few decades after the Russian biologist Dmitri Ivanovsky (1864-1920) discovered viruses in 1892—did humans become aware of coronaviruses, first in chickens, then in mice, and later in humans and other animals.

Coronaviruses became a topic of worldwide significance following the November 2002 report of an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Guangdong Province, China. Between its first identified appearance and July 2003, roughly eight thousand cases of SARS were confirmed globally, mostly in China. Of the twenty-seven cases identified in the United States, at least eleven came from Pennsylvania and three from New Jersey. Although the first probable case in Greater Philadelphia likely came from exposure in Toronto, the virus’s association with East Asia hit business owners in Philadelphia’s Chinatown, who reported income declining by as much as 60 percent in April 2003. Philadelphia International Airport screened new arrivals, and some individuals wore masks to curb spread. Limited human-to-human transmission made containment possible both locally and globally.

COVID-19 Emerges

Sixteen years later, a more transmissible coronavirus proved far harder to contain. In December 2019, epidemiologists and local health officials noticed a mystery pneumonia in Wuhan, China. By examining patients’ airway cells, a team of Chinese researchers identified a novel coronavirus—which they dubbed 2019-nCoV—as the cause of the outbreak. The virus—later named COVID-19 by the World Health Organization—spread rapidly, affecting more than two dozen countries by mid-February 2020.

In the Philadelphia area, officials from the city’s public health preparedness program and similar programs in suburban counties urged preparation over panic. The Inquirer noted in early February 2020 that the flu remained “more dangerous” than “the scary new virus.” Despite such attitudes, on March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus a pandemic, which recognized the virus’s international spread. In the wake of the World Health Organization’s announcement, disease control specialists increasingly advocated “social distancing,” or the restriction of physically close interpersonal intimacy, as well as mandated mask-wearing and shutdowns, despite concerns that some such mitigation strategies could violate individual human rights. Public health experts in the United States and elsewhere often pointed to Philadelphia’s erratic implementation of such measures during the city’s catastrophic 1918 flu epidemic to make the case for restrictions.

In late March 2020, Philadelphia experienced its first COVID-19 death. The number of confirmed cases in the Philadelphia area grew rapidly between March and May 2020. In response, federal, state, and local authorities adopted emergency measures to slow transmission. On March 12, the city government barred gatherings of over a thousand people; on March 16 it closed public schools and nonessential businesses; and on March 22 it issued a stay-at-home order. The switch to work from home and closure of cafes and restaurants left downtown streets deserted. Other jurisdictions adopted similar restrictions. The governor of New Jersey, Phil Murphy (b. 1957), ordered residents to stay at home on March 21, while his counterpart in Delaware, John Carney (b. 1956), did so a day later. On March 23, Governor Tom Wolf (b. 1948) of Pennsylvania followed suit, with an executive order that covered Philadelphia and nearby counties. Soon after the announcement of the first COVID-19 death in Philadelphia, local hospitals prepared for a surge of patients that could overwhelm their capacity. By the end of March lockdowns extended across the Greater Philadelphia region.

The widespread shutdowns in the spring of 2020 spurred debates about weighing individual liberties against the greater good. However, public health experts at Drexel University’s Urban Health Collaborative estimated that the first forty-five days of shutdown in the city prevented 6,200 deaths. Other measures also attempted to slow transmission. In June Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney (b. 1958) signed a mask mandate for indoor and busy outdoor locations and by September, eighty contact tracers—including a group of thirteen Community College of Philadelphia students—worked to curb the virus’s spread. Even with such measures, COVID-19 strained the region’s health care. As more and more victims succumbed to the disease in mid-April, one local hospital resorted to transferring body bags to the Medical Examiner’s Office in the back of a pickup truck. Recognizing the traumatic impact of the pandemic on the region, historians, librarians, and archivists in Greater Philadelphia urged members of the public to document their experiences for use by future historians.

Later Waves of the Pandemic

COVID returned after its deadly first wave. Cases spiked again in November and December 2020, with over seven thousand testing positive in the city during the week after Thanksgiving. A smaller surge followed in the Spring of 2021. By mid-August 2021, the city had reported over 160,000 positive COVID tests, and a month later the death toll stood at thirty-eight hundred. Some groups—notably people of color, prison inmates, and undocumented workers—struggled to access testing, care, and financial support. Additionally, COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths tended to cluster in neighborhoods with larger minority and low-income populations, following a pattern seen in epidemics that stretched back to the eighteenth century. This data prompted the Philadelphia Department of Public Health to craft a racial equity plan in July 2020 to improve access to testing and care, with the ambitious long-term goal of reducing the disparate impact on communities of color by preventing chronic health conditions that increased the risk of severe COVID-19 infection.

Vaccines, which rested in part on a revolutionary discovery by Philadelphia scientists, offered a more immediate route to limiting the death toll. On December 16, 2020, hundreds of Philadelphians who worked in medical settings received their first doses of a COVID-19 vaccination, which markedly reduced the likelihood of serious illness. The rapid development of a vaccine owed much to the research of University of Pennsylvania-affiliated biochemists Katalin Karikó (b. 1955) and Drew Weissman (b. 1959), whose work in the 1990s and early 2000s established how to modify messenger RNA (mRNA) to “teach” the human immune system how to resist infections. The mRNA vaccines produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna became by far the most widely used vaccines in the United States, Europe, and parts of Africa and the Americas, while by 2023, China too had embraced the technology in its fight against the virus. Locally, almost two-thirds of Philadelphia residents were fully vaccinated against COVID by June 11, 2021, when the city “reopened” by relaxing restrictions, although schools did not welcome back students fully until August. In 2023, Karikó and Weissman won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for their medical breakthrough.

Although vaccines provided strong protection against serious illness, they proved less effective at blocking the virus’s spread. The emergence of the BA.2 subvariant in the spring of 2022 led to another dramatic shift in pandemic response, as well as to renewed confusion. Effective April 18, 2022, Philadelphia reinstated its indoor mask mandate, becoming the first major U.S. city to do so. Later that day, U.S. District Judge Kathryn Kimball Mizelle (b. 1987) of Florida struck down the federal mask mandate for public transportation. Mizelle’s decision prompted transit agencies SEPTA and PATCO to rescind their own mask mandates, despite Philadelphia’s new mandate coming into effect the same day.

Vaccines and immunity acquired from infection made these later waves of COVID far less deadly than the initial surges of 2020-21. Nonetheless, the regional toll of the virus proved chastening. As of July 2023, COVID had claimed the lives of over 5,600 Philadelphians and over 8,000 in adjacent Pennsylvania counties. By then, almost 1,700 had also succumbed to the disease in New Castle County, Delaware, with nearly 4,500 New Jerseyites in Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, and Salem Counties dying. According to the team of Chinese researchers who first identified the virus that causes COVID-19, though, the risks of future spillover events involving coronaviruses remained.

Timothy Kent Holliday is a Lecturer in the Critical Writing Program at the University of Pennsylvania, where he received his Ph.D. in History in 2020. He is a historian of early America, focusing on the history of the body. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2024, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- With new COVID boosters, Philly health workers are trying to expand their reach—but face new challenges (WHYY, September 21, 2023)

- Philly jobs market bounced back but business bankruptcies start to creep higher since COVID-19 (WHYY, June 23, 2023)

- Philly small business grants up to $10K available before COVID-19 relief money runs out (WHYY, February 21, 2024)

- Philadelphia achieves near complete compliance with city employee vaccine mandate (WHYY, August 9, 2022)

Links

- Dmitri Josifovich Ivanovski (1864-1920) (Bacteriological Reviews)

- CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- COVID-19 Aggregate Death Data Current Monthly County Health (OpenDataPhilly)

- COVID Tests and Cases (OpenDataPhilly, City of Philadelphia)

- New Jersey COVID-19 Dashboard (State of New Jersey)

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) Data Dashboard (State of Delaware)