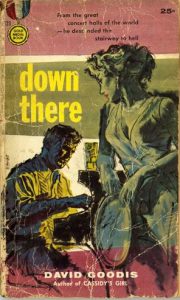

Down There

Essay

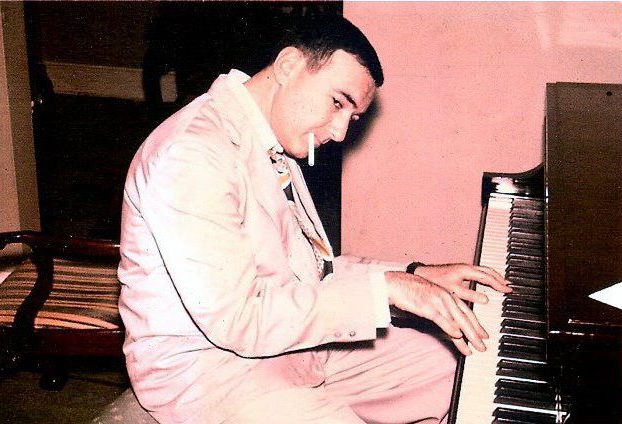

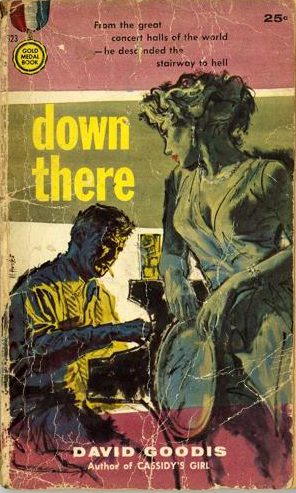

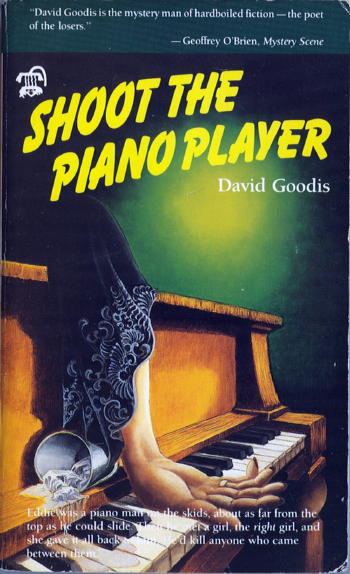

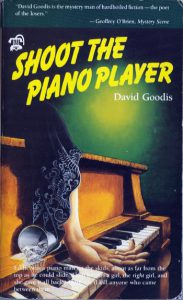

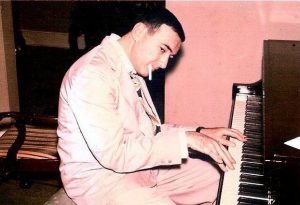

Down There, a hardboiled crime novel by Philadelphia writer David Goodis (1917-67) published in 1956, follows Eddie Lynn, a former concert pianist, who hides from his past until his estranged brother shows up and forces him to grapple with his ghosts. Although not one of Goodis’s most successful novels, Down There became his most famous after being adapted into the well-regarded French film (directed by Francois Truffaut) Shoot the Piano Player, the title by which it is best known.

The novel opens on a beaten man, Turley, stumbling through 1950s Port Richmond in Philadelphia. Running from two assailants, he hides in a dive bar, where he finds his piano-playing brother, Eddie. The two men follow him inside and Eddie facilitates Turley’s escape, thus setting up Eddie’s reluctant involvement in what becomes a few long nights of cat and mouse through the streets of Port Richmond, as Eddie and a waitress, Lena, who befriends him, try to stay one step ahead of this criminal element. Eventually, the pair escapes to Eddie’s family’s home in South Jersey, where his two criminal brothers are waiting for the fellow criminals they duped to find them.

This narrative is memorable for several reasons, one of which is its vivid portrayal of Port Richmond, a working-class neighborhood heavy in industry that boasted small houses that were a bit “shabby,” in Northeast Philadelphia. Although the book’s thin plot focuses on Eddie’s handling (or avoidance) of the deep grief over his wife’s suicide while he’s on the run, the story is really about how to pull (or accede to being pulled) from grief. The setting allows Eddie to both avoid his profound grief until Turley arrives as well as force him to confront it, finally, as he must get safe from the trouble that’s found him. The setting is also responsible for his salvation, such as it is, in the end.

As rendered by Goodis, Philadelphia’s Port Richmond offers a safe haven for any person looking to disappear amidst its working-class residents—there, no one pesters Eddie to pursue his dreams; he’s left alone in the bar as he plays to a mostly seemingly-indifferent crowd. But this environment is not judged harshly by the author; rather, the novel is in many ways a nod of respect to the type of establishment easily mistaken for a trashy dive bar. In Harriet’s Hut, the working-class clientele, mostly local mill workers, slump over drinks in the beat-up interior. Tough women work the bar while patrons keep an eye on intruders into their world, such as Turley in the opening chapter. Furthermore, when Eddie is trying to dodge the two goons, he feels “protected” on these streets, as if the neighborhood is looking out for him. Eddie’s saving at the end also hinges on this working-class neighborhood. The residents lie to protect his “accidental” killing of Hugger, even allowing him to return to their world to play piano. He’s clearly unhappy, but at least he belongs.

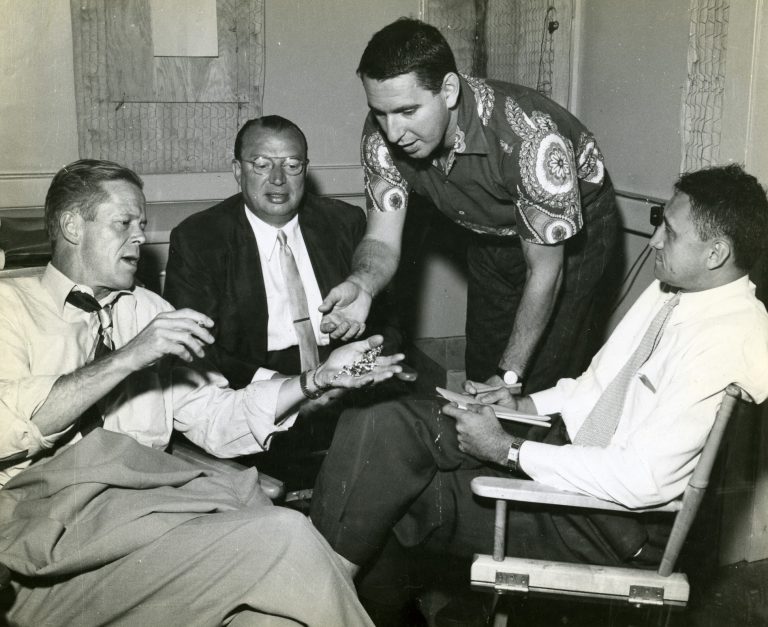

While some critics have suggested that Goodis mocks his working-class characters, others have noted the likely source of the eventual strength Eddie finds: the community. The story does not paint a pretty picture of Philadelphia, but it suggests that it was stronger during the 1950s than non-residents realized or would have given it credit for. Goodis demonstrated his mastery of conveying urban angst over the course of his 18-novel career.

Brad Windhauser is a Philadelphia-based writer whose short stories have appeared in several literary journals. He has published two Philadelphia-set novels: Regret (2007) and The Intersection (Fall 2016). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History