Episcopal Church

Essay

The Protestant Episcopal Church, established in 1789, was the heir of the Church of England in the newly formed United States. The Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania, which encompassed the church in the Philadelphia region, became known as the “mother diocese” of the denomination because of its founding role. The name of the denomination—the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America—emphasized the Protestant roots of the church, but over time a growing emphasis on the denomination’s historic liturgical traditions led the General Convention in 1964 to authorize the simpler designation of the Episcopal Church, without officially abandoning the original name.

The Protestant Episcopal Church emerged out of the aftermath of the American Revolution, when it became clear that maintaining ties with the Church of England was both impractical and repugnant: The Church of England was a national church headed by the British monarch, and it required prayers at services for the monarchy. Its clergy, at the time of their ordination, had to swear an oath of loyalty to the Crown. Neither requirement was acceptable to citizens of the new American republic, and those concerns led to the establishment of an American church, independent in its organization while remaining somewhat loosely part of the larger Anglican Communion.

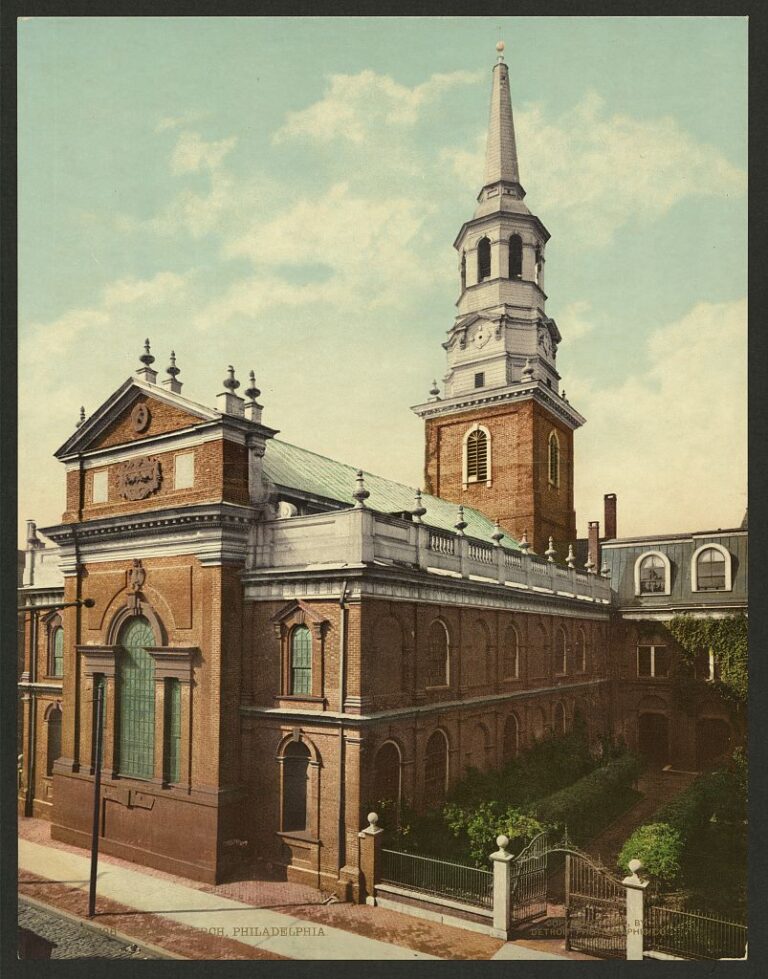

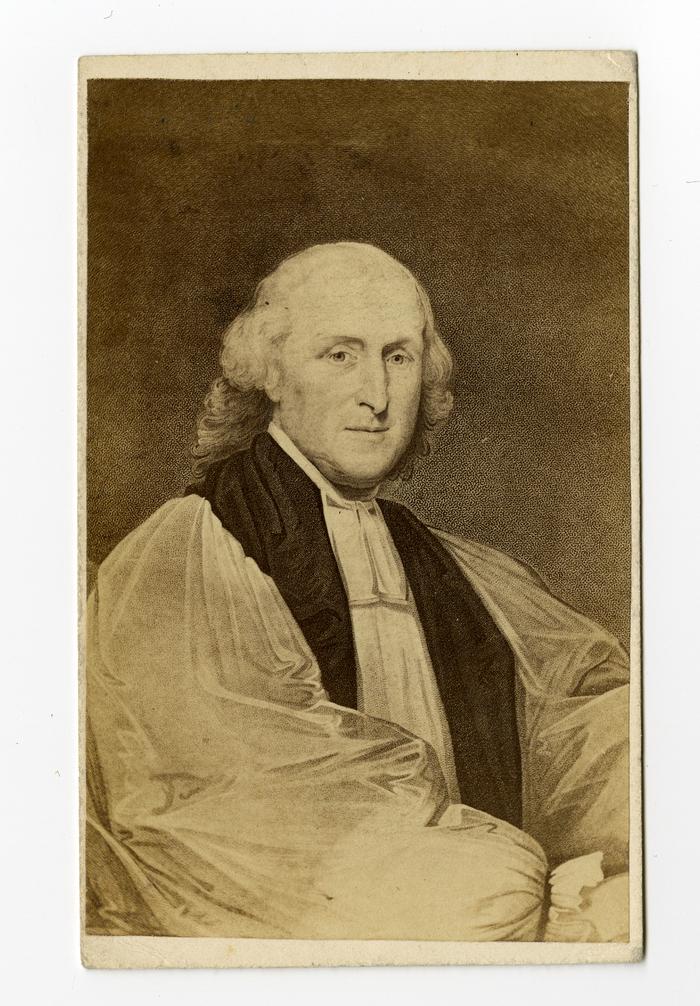

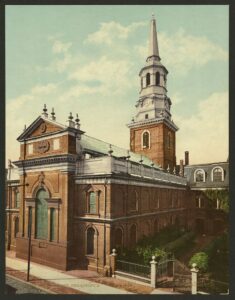

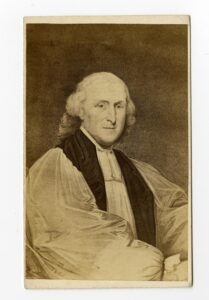

William White (1748-1836), the rector of Christ Church, Philadelphia, while still an official part of the Church of England and then first bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania (established in 1784), used his genius for compromise to preside over the birth of a separate American church that retained much of the form and many of the traditions of the Church of England. Delegates met at Christ Church to establish an American church during the summer of 1789, at the same time that the newly minted government under the United States Constitution was taking effect. The delegates drafted an American Book of Common Prayer, developed a governance structure of elected bishops, and created a bicameral policy-making body made up of a House of Bishops and a House of Deputies, whose lay representatives were also elected. White served as presiding bishop of the national church from 1795 until his death in 1836.

Regional Dioceses Established

Initially, the Diocese of Pennsylvania comprised the entire commonwealth, but between 1865 and 1910, it was divided into five regional dioceses, with Philadelphia and its surrounding counties retaining the original name of the Diocese of Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, separate dioceses formed in Delaware and New Jersey. The Episcopal Diocese of Delaware, which was originally the Anglican Diocese of Delaware (later changed to the Episcopal Church of Delaware), traced its founding to 1786, when delegates to a state convention decided to form a separate diocese from Pennsylvania, with its cathedral church in Wilmington. The Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey, founded in 1785 as the Anglican Diocese of New Jersey, originally included all of the state, but in 1874 divided into the Episcopal Diocese of Newark, which covered the northern part of the state, and the Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey, with its cathedral church in Trenton, which encompassed South Jersey.

Philadelphia-area Episcopalians and others in the nation have often juggled dual impulses. They have seen their denomination as being both Catholic and Protestant—a “reformed” church with bishops regarded as successors to Christ’s apostles but nevertheless providing a generous degree of decentralization and lay governance. Even though the Protestant Episcopal Church has remained part of the wider “Anglican Communion,” Episcopalians, both locally and nationally, have often claimed, in seeming contradiction, to be the most American of the Christian denominations in the United States. Another duality of the church has been its emphasis on tradition, while in the best of times willing to accommodate change. For example, most Episcopalians have rejected a literal reading of the Bible, a position that some Episcopalians liken to a “four-legged stool” in which scripture should be understood in light of reason, tradition, and experience.

Episcopalians also have tended to embrace a “latitudinarian” approach to faith and worship derived from the time of England’s Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603). The major facet of this stance, known as the Elizabethan compromise, has required Episcopalians to use the words of the Book of Common Prayer but has permitted worship practices to vary, so that individual parishes run the gamut from “high church” (including what is called Anglo-Catholic practice) to “low church” (including but not exclusively evangelical parishes). This “middle way,” as the compromise has sometimes been known, has proved both a strength and a weakness, since it allows for variety but also has invited controversy. This lack of a strict, doctrinaire attitude may also help to explain why the Episcopal Church has long been a denomination of converts. In the early twenty-first century, only one-third of its members, locally and as well as nationwide, could call themselves “cradle Episcopalians”—that is, born into Episcopalian households.

Overcoming an Upper-Class Label

In the early decades of the diocese and the national church, Episcopalians struggled to compete with other denominations in Philadelphia and the surrounding region, in large part because of the church’s reputation as an upper-class denomination and its associations with England. By the industrial era of the second half of the nineteenth century, a time of increasing wealth and social aspiration, the number of parishes increased from 113 to 138 at the same time that the number of clergy climbed from 176 to nearly 300. This growth was due in part to many newly wealthy Philadelphians becoming Episcopalians as a way of associating themselves with families of “old money” or social respectability. In looking for social and cultural models, many looked to England, becoming Anglophiles in attitudes and tastes. Contributing to this Anglophilia was the Oxford Movement, a complex phenomenon that began at Oxford University in England and that, among other things, emphasized the medieval Catholic roots of the Church of England.

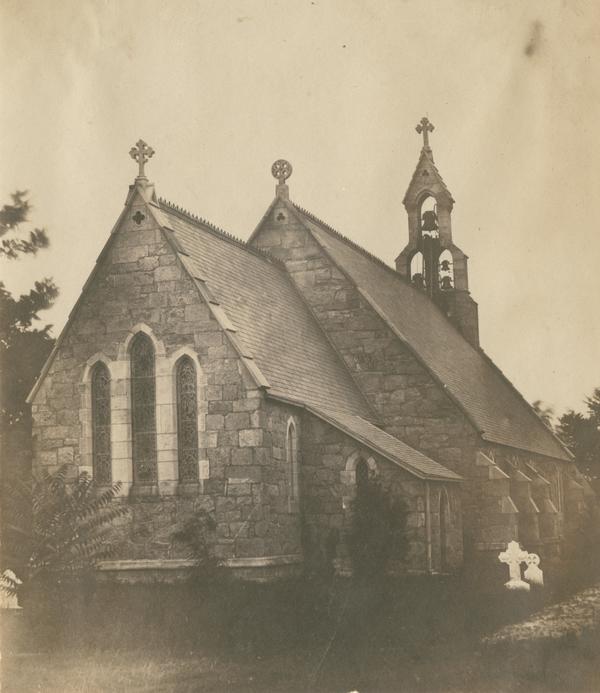

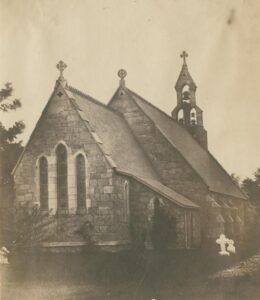

For Episcopalians, the Oxford Movement strengthened high church attitudes and stimulated the Gothic Revival in church architecture and decoration. Among the earliest of the Gothic-style edifices was St. James the Less (completed in 1850), at Clearfeld Street and Hunting Park Avenue in the East Falls section, then outside the city limits but later consolidated into Philadelphia. Designed by Robert Ralston (1795-1858) and John Carver (1803-59) and inspired by thirteenth-century English country churches, St. James the Less became a model for other Gothic Revival churches in the United States. Another impressive example of this style was St. Mark’s Church at 1625 Locust Street, designed by the celebrated Scottish-born, Philadelphia architect John Notman (1810-65) and completed in 1851. Dozens of other Gothic-style Episcopal churches went up in Philadelphia and environs, including St. Timothy’s, Roxborough (1862); the Church of the Redeemer, Bryn Mawr (1881); St. Thomas, Whitemarsh (1881); St. Martin-in-the Fields, Chestnut Hill (1889); the Church of the Good Shepherd, Rosemont (1894); and St. Paul’s, Chestnut Hill (1929). In Wilmington, Delaware, the Cathedral Church of St. John (1858), built of Brandywine blue rock, exemplified the Gothic style and cruciform design that was intended not only to inspire faith but also to encourage surrounding development. The crowning achievement of Gothic construction in the Philadelphia region was supposed to be the diocesan cathedral in Upper Roxborough (officially known as the Cathedral Church of Christ), undertaken by Bishop Philip Mercer Rinelander (1869-1939) after the diocese purchased a one-hundred-acre site to build a cathedral complex in 1927. Due to a lack of funds, the grand cathedral was never completed, and in 1992, the diocese dedicated the large and impressive Church of the Saviour in West Philadelphia as its cathedral.

Philadelphia-area Episcopalians combined their interest in grandiose physical structures with concerns for social and economic reform. In the late nineteenth and into the twentieth century, amid problems created by rapid industrialization and urbanization, Philadelphia-area Episcopalians became involved in the Social Gospel movement, which called on Christians to practice the social teaching of Jesus as a way of addressing poverty and injustice. In pursuit of such interest, the Philadelphia diocese founded such institutions as the Lincoln Institute for Orphaned Boys, the Sheltering Arms Association for abandoned children and unwed mothers, All Souls Church for the Deaf, Episcopal Hospital, the Church Dispensary, St. John’s Settlement, the Church Farm School in Chester County, and the City Mission, which later became Episcopal Community Services.

Perhaps the most impressive parish efforts toward fulfilling the Social Gospel came out of historic Christ Church, Philadelphia, at Second and Market Streets. In 1915, the parish established Christ Church Neighborhood House to serve what was then a low-income population in surrounding neighborhoods. Occupying a handsome, two-story brick building beside the church that included a large gymnasium on the second floor, the Neighborhood House operated a soup kitchen, a shelter for stranded travelers, a childcare center, boys and girls clubs, a low-cost luncheon service for workers in the area, and a performance venue. Social outreach in the diocese included work with African Americans in the city. In 1910, for example, the diocese established the League for Work Among Colored People. In addition to a sincere dedication to carrying out the Gospel message as a testimony of faith, many wealthy Episcopalians acted from a sense of noblesse oblige—an obligation on the part of the well-off to assist those who were not so fortunate.

Early Ambivalence Toward Racism

Most white Episcopalians held ambivalent attitudes toward Black people, including members of their own church. White Episcopalians generally accepted prevailing views about race, and the diocese did not become significantly active in addressing racial prejudice and injustice until the mid-1960s era of the nationwide civil rights movement.

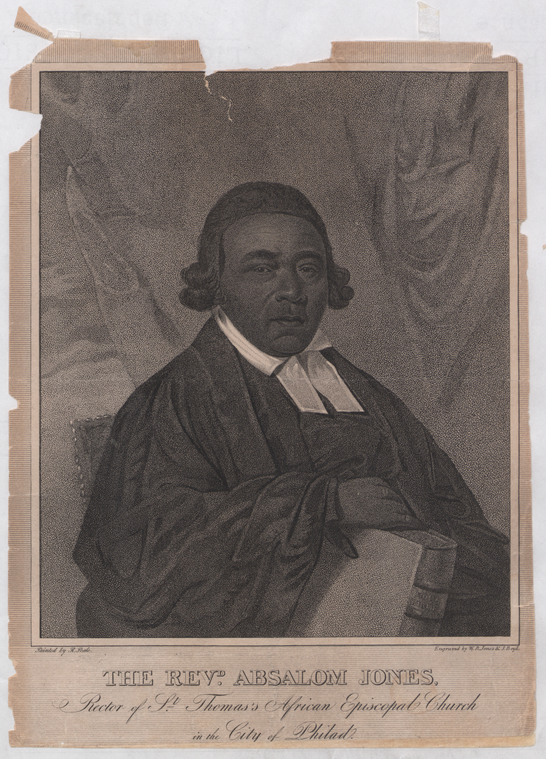

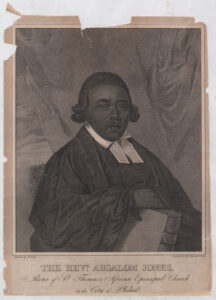

Before slavery was abolished in Pennsylvania, wealthy Anglicans frequently had their enslaved people baptized at church, and some sought to educate free Black people in special schools. After Pennsylvania passed a gradual abolition law in 1780, some free Black individuals continued to attend the newly formed Episcopal Church. White congregants saw exposure to religion as a way of tamping down what they considered to be the undisciplined habits of some African Americans, but they had no intention of admitting them to an equal status in the church. Accordingly, Black Episcopalians established the segregated African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in 1794, with Absalom Jones (1746-1818) as its leader. Within a year, the parish counted some five hundred members, becoming the mother church of Black Episcopalians. Nevertheless, Bishop White designated Jones as a deacon and did not promote him to the priesthood for another decade, and Jones was never invited to attend the annual conventions of the diocese. (St. Thomas was not permitted to send delegates to the convention until 1864.) This slight persisted even though the social profiles of Black Episcopalians in many ways reflected those of white members of the denomination: They tended to be economically prosperous and generally well-educated individuals who could claim some measure of professional or commercial success, who were drawn to the sober and formal types of worship associated with the Episcopal Church. Additional African American Episcopal parishes were founded in the diocese over the decades, and from the 1960s on many formerly white parishes became largely Black or all Black as neighborhoods changed demographically.

With some exceptions, Episcopalians in the diocese, like the majority of Philadelphians, did not take an active role in opposing slavery during the years leading to the Civil War. Philadelphia merchants had long done a brisk business with the southern states, transporting their goods up and down the Atlantic Coast and to Europe, while other Philadelphians sold them banking and insurance services. Significant intermarriage also occurred between wealthy Philadelphia Episcopalian families and those in the South, especially from Charleston, South Carolina, all of which led to considerable sympathy with the South. To the extent that Episcopalians and other well-to-do Philadelphians supported the subsequent Civil War, they did so more to preserve the Union than to put an end to slavery. Yet the war did cause churches to assess their ministry and their civic obligations—none more visibly than Christ Church, where the congregation divided over such issues as slavery and emancipation. The church emerged from the war as a more “northern” church with a decidedly Republican character.

Individual Episcopalians supported Reconstruction and educational efforts for Black people in the South, but the church took no official position. Episcopalians along with most whites in the Philadelphia region did not question the doctrine of “separate but equal” regarding legal racial segregation or invest much in improving conditions for Black residents of Philadelphia, Wilmington, Camden, or elsewhere.

The Pennsylvania diocese did little about racial disparities until the election of Robert L. DeWitt (1916-2003) as bishop in 1964. He insisted that all Christians were duty-bound to live out the principle of the equality of all humans. DeWitt supported the integration of Philadelphia’s Girard College, which had been limited to “white, orphaned boys.” He joined other Episcopal clergy and laity, along with individuals from other faith communities and the general public, to picket the institution, which was successfully integrated in 1969 after a fourteen-year effort. DeWitt also embraced the so-called Black Manifesto, which various Black clergy and other civil rights activists drew up in Detroit in the summer of 1969, demanding that white Christian churches and Jewish synagogues pay a half-billion dollars in restitution for harm done to Black people during and after slavery. Agreeing with the justice of these demands, DeWitt established a Task Force for Reconciliation, which set up a fund of $500,000 (later augmented to $675,000) to be administered by Black communities for their own benefit. More than a few Episcopalians withheld financial contributions from the diocese in protest against their bishop’s activism on behalf of racial justice. Still, from the mid-1960s into the early twenty-first century, the diocese, individual parishes in the region, and various committees and organizations associated with the church sponsored a variety of efforts to encourage racial understanding and to heal the wounds of the past.

Role of Women Progresses

The diocese also advanced the role of women. From a very early period, women engaged in a variety of fundraising activities such as organizing church fairs and bazaars to provide funds for special projects. During the 1830s Episcopal women were managing the Magdalen Society Asylum, founded by Bishop White to rescue prostitutes who were “desirous of returning to a life of rectitude.” Two decades later, women from Christ Church established the Dorcas Society, which provided free clothing for the poor. The most widespread women’s activity was support for the church’s missions. In 1872, the national church established the Women’s Auxiliary of the Board of Missions, with branches in almost every parish in the Philadelphia region. Although these organizations were later criticized for consigning women to subordinate roles in the church, they gave women opportunities to develop organizational techniques and to take up leadership roles. The women also learned much about fundraising, as, for example, in their important roles in supporting missionary work overseas. And Episcopalian women missionaries in the field frequently worked to provide educational opportunities and improved working conditions for women.

However, when it came to governance in the church, women had no official role for more than a century and a half after the founding of the diocese. By the early 1950s, several parishes finally permitted women to serve on vestries (a type of lay parish council), and in 1956 the annual diocesan convention voted to allow women to serve as delegates. Nearly two decades later, Bishop DeWitt led the call for the full inclusion of women in the Episcopal Church when he arranged to ordain the first women as priests. In 1973, the triennial convention of the national church had narrowly voted down a proposal for the ordination of women. Then in February 1974, soon after he had stepped down as Bishop of Pennsylvania, DeWitt, joined by three other bishops, ordained eleven women to the priesthood at Philadelphia’s Church of the Advocate. Two years later the general convention finally approved women’s ordination.

Questions of sexuality stirred far more controversy and opposition within the church. In the 1980s, the national church passed several resolutions condemning discrimination against the gay community and those suffering from AIDS. In 1989, Bishop Allen Bartlett Jr. (b. 1929) appointed a fourteen-member commission on human sexuality. Four years later Bartlett ordained as a deacon a gay man who had been in a committed same-sex relationship of twenty years. This action led several conservative parishes and their members to form a group called Concerned Episcopalians that opposed gay ordination on doctrinal and biblical grounds. In 1999, the vestry of St. James the Less, an Anglo-Catholic parish in the East Falls section of Philadelphia, voted to disaffiliate itself from the diocese and claimed ownership of the property. Two years later the diocese filed suit, and in 2006 the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that the property remained in the ownership of the diocese. In 2002, the diocese deposed the rector of Good Shepherd, Rosemont, another Anglo-Catholic parish, when he and his vestry refused to allow the bishop to make visitations because of the position of the local diocese and the national church position on the question of gay ordination.

As Elsewhere, Membership Declines

By the second decade of the twenty-first century, membership in the local diocese had declined from a high of 84,000 in 1962 to 41,000 in 2017. The church’s controversial stands on race, gender, and sexuality likely contributed to falling numbers, but the Episcopal Church was not unlike other historic, “main line” Protestant denominations in their declining membership—beset as they were by low birthrates, the growing secularization of American society, widespread anti-institutionalism, and strong competition from more evangelical denominations. The number of parishes in the diocese declined during the same period from approximately 170 to 155. The fall-off in parishes reflected socioeconomic changes in urban neighborhoods and the movement of Philadelphians to the surrounding suburbs. Similar declines and migration occurred in the Delaware and New Jersey Episcopal dioceses.

Indicative of the changes underway was the closing of historic Gothic-style St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, at Tenth and Ludlow Streets, to worship in 2017 and its repurposing as a social service community center in 2019. At the same time, the Pennsylvania diocese moved its headquarters to the Gothic-style St. John’s Episcopal Church, in Norristown, Montgomery County. Similarly, the Diocese of Delaware closed its Cathedral Church of St. John in Wilmington in 2014, after serving the diocese for 150 years, because it could not afford maintenance costs and the church was not attracting enough worshipers to sustain it. Even some suburban churches consolidated or moved to share clergy, due to a lack of ordained ministers and declining membership, as, for example, did Christ Church Ithan and St. Martin’s Church in Radnor in 2020.

Despite these changes, the Episcopal Church remained a significant presence in the Philadelphia region, with its many handsome surviving church buildings, social programs, and continued prominence among the region’s social and economic elite.

David R. Contosta is professor of history at Chestnut Hill College and the author of numerous books on a variety of subjects, many devoted to aspects of Philadelphia history. These include A Philadelphia Family: The Houstons and Woodwards of Chestnut Hill; Suburb in the City: Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia; A Venture in Faith: The Church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields; and co-author of Metropolitan Paradise: Philadelphia’s Wissahickon Valley. He is also editor and co-author of This Far by Faith, a history of the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2024, Rutgers University.