Free African Society

By Elise Kammerer | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

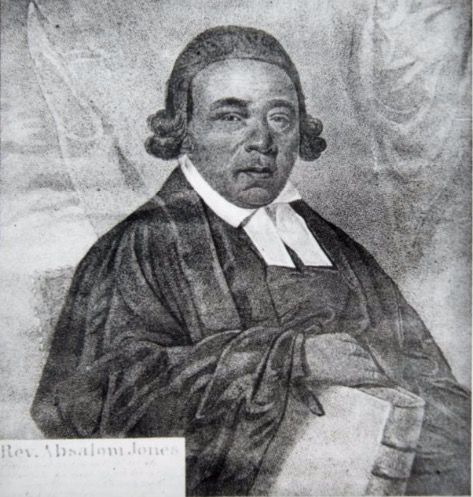

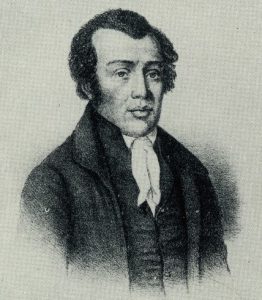

Headed by Black founding fathers Richard Allen (1760-1831) and Absalom Jones (1746-1818), the Free African Society was founded on April 12, 1787, as a nondenominational mutual aid society and the first dedicated to serving Philadelphia’s burgeoning free Black community. Members contributed one shilling per month to fund programs to support their social and economic needs.

The Free African Society emerged from discussions among Allen, Jones, and other men in early 1786, when Allen was leading prayer meetings and early-morning services for Black congregants of St. George’s Methodist Church. Concerned that the majority of Philadelphia’s Black community was illiterate and did not go to church, these men decided to form a nondenominational, religious society to promote religion and literacy, as well as assisting members’ families to help cover the costs of burial after a member’s death.

To join the Free African Society, prospective members agreed to pay the monthly dues and to abide by moral requirements to be temperate and refuse to engage in disorderly behavior. Members of any religious denomination could join, but anyone who behaved in disorderly ways, abused alcohol, or did not pay their dues faced expulsion. By demanding that members abstain from feasts, drinking, and gambling, the society’s officers sought to combat beliefs that Black people were lazy, disorderly, or frivolous—claims often deployed as a justification for slavery. They also argued that indulgence in the “sins” of drinking, gambling, or idleness showed a lack of respect for Black people still enslaved.

Members in good standing could expect a number of benefits from the mutual aid fund. Particularly in the first years of the society, important aspects of support for members included payments for burials and providing financial aid for widows and other family members of the deceased, finding apprenticeships for children to learn a trade, and paying tuition for members’ children if places in free schools were not available. Over time, the society expanded to care for the social and economic well-being of its members by providing moral guidance, by helping newcomers to the city feel welcome, and by giving assistance during periods of financial difficulty brought on by unemployment or sickness. The society also took on the task of assisting the sick during the yellow fever epidemic in 1793. Members nursed the sick, dug graves and buried the dead, and transported the ill to quarters outside of the city where they could be quarantined and given medical aid.

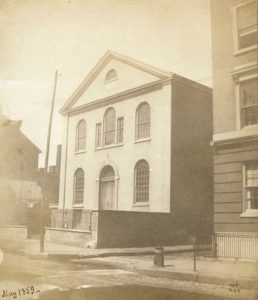

Ultimately, the nondenominational nature of the Free African Society brought about a schism that led to the society’s demise. Allen, a Methodist, became disillusioned with the society’s reliance on Quaker principles such as observing fifteen minutes of silence before meetings or having a committee visit members’ houses to ensure they were living morally. In 1794, Allen broke away from the society, and some members followed him to become members of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, founded in the same year. After Allen’s departure, the remaining members of the society gravitated toward Absalom Jones’s African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, where many of the remaining members began to worship.

Though the Free African Society was not particularly long-lived, it spurred the creation of many similar African American mutual aid societies, more than one hundred in the Philadelphia region by 1838. The society’s mission of community building and assisting one another also contributed to the self-sufficiency of Philadelphia’s growing free Black community. Not only did the churches founded by Jones and Allen become cultural and religious centers of the community, but free Black Philadelphians also began moving to the neighborhoods around the churches, close to shops, businesses, and schools operated by former members of the Free African Society.

Elise Kammerer is a Ph.D. candidate in American history at the University of Cologne, where she specializes in free Back education in early national Philadelphia and the antislavery movement in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People . . . (PBS)

- Petitioning for Freedom (National Archives)

- Richard Allen: Apostle of Freedom (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment, via YouTube)

- Richard Allen: Apostle of Freedom (Online Exhibit, Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Black Founders: The Free Black Community in the Early Republic (Library Company of Philadelphia)

National History Day Resources

- Preamble (1778) and Articles of the Free African Society, 1787 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793, published in 1794 (National Library of Medicine)

- Petition Against the Slave Trade, 1799 (DocsTeach)

- Richard Allen’s “Address to the Free People of Colour of these United States,” 1830 (PBS)