Fugitives From Slavery

Essay

Immediately after passing the nation’s first gradual abolition law in 1780, Pennsylvania became a haven for enslaved people escaping from neighboring states, putting the state at odds with slaveholders throughout the South and causing tension with Maryland in particular. Though New Jersey also attracted escaping slaves, and whites in both states had mixed reactions to the newcomers, Pennsylvania’s location on the Mason-Dixon Line created a unique situation that influenced local and national attitudes about the issue of slavery.

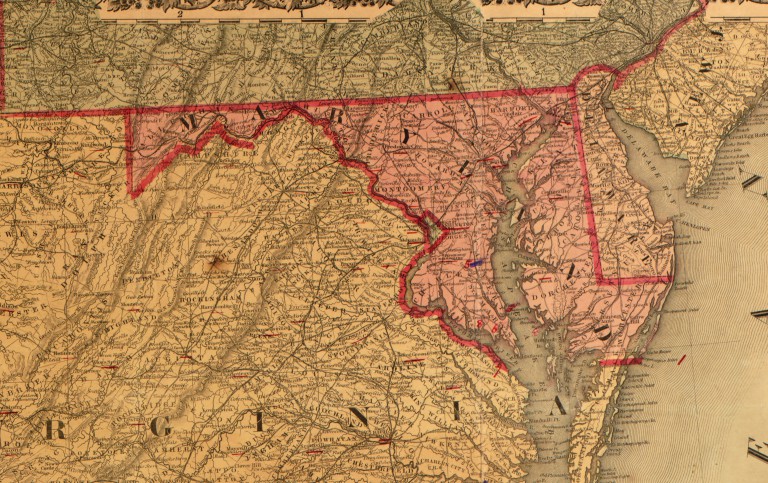

Tension permeated this region where slavery and freedom sat side by side. By the time of the drafting of the U.S. Constitution seven years after Pennsylvania passed its abolition law, all northern states except New York, New Jersey, and Delaware had made provisions to end slavery, at least gradually. This left the nation divided along the Pennsylvania-Maryland border—the Mason-Dixon line—with Pennsylvania as the first free state north of the line and Maryland the first slave state to the south.

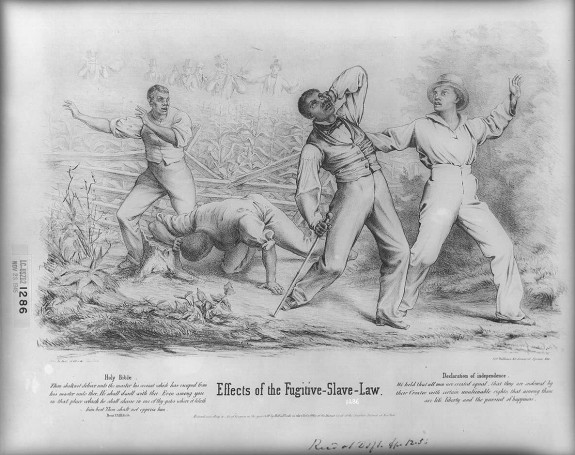

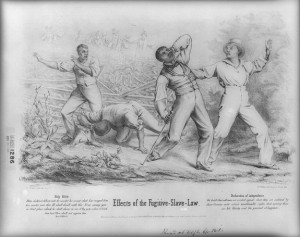

Questions arose over whether slaveholders could take their human property into non-slave states or retrieve runaways. The U.S. Constitution sought to answer questions like this by regulating the relationship between states, and in 1793, while Philadelphia served as the nation’s capital, Congress took the matter further with a Fugitive Slave Law that enforced the return of anyone bound to labor in one state and fleeing to another. As sectional animosity reached its zenith, legislators offered a second Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 that required state and local authorities to assist in the recapture of runaways. Pennsylvania abolitionists resisted both laws through legal means and efforts to gain public sympathy for the fugitives.

Slave Catchers and Kidnapping

While fugitive laws aimed to return runaways to slavery, they also placed northern free Black people in jeopardy of being kidnapped by eager slave-catchers. In response, in 1811 the Pennsylvania Abolition Society (PAS) began pushing for the first state personal liberty law, eventually passed by the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1820. The law imposed fines and jail sentences for kidnappers of suspected fugitives and required judges to file reports any time they deemed someone a fugitive and returned him or her to slavery. Combined with abolitionists’ resistance to slavery and the slave trade and their reputation for assisting free Black people, the personal liberty law encouraged many fugitives from slave states, especially nearby Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia, to head straight for Pennsylvania.

Slaveholders throughout the U.S. reacted swiftly in characterizing Pennsylvania as an enemy to their interests. Maryland slaveholders and legislators were especially unhappy with the personal liberty law, viewing it as an impediment to their right to lawfully pursue fugitives. With debates also raging over whether slavery would be extended into new territories, beginning with Missouri, more and more people began to question how free states and slave states could coexist as enslaved people sought refuge in free states and slave catchers kidnapped free Black people from free states.

As the tensions between freedom and slavery heated up during the antebellum years, abolitionists working to protect free Black people sometimes extended their efforts to safeguard fugitives as well. Throughout the border North, notably in southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey, antislavery leaders stressed that slave catchers were disregarding the rights of states to legislate for themselves on the matter of slavery. This led to outcries that the “slave power” was seeking to force slavery on the entire nation. As a result, some mid-Atlantic whites began to call upon their states to adopt personal liberty laws. One successful example was the 1820 Pennsylvania law that focused primarily on providing jury trials for accused fugitives.

Defending Accused Fugitives in Court

Abolitionist lawyers such as William Rawle (1759-1836) and Evan Lewis (1782-1834) defended accused fugitives in court from the early days of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. One of the more famous attorneys, Quaker David Paul Brown (1795-1872), represented and won freedom for a number of Black Americans during his forty-year career. Freedom suits grew even more complicated after the passage of the Compromise of 1850 and its controversial Fugitive Slave Law. At this point, as historian Charlene Mires has shown, the old Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall) became the scene of a number of heated cases in which whites accused Black individuals of being fugitives and the accused and their abolitionist allies fought to establish their freedom. In one case, a man named Henry Garnet ran out of the courtroom celebrating his newly-granted freedom, only to be arrested by police who assumed he was attempting an escape. This case in particular illustrates the precarious position of the men and women who pleaded their cases in the building that, by that time, was celebrated by many as the birthplace of American liberty.

While abolitionists took their cases to the courts, free Black people and their white allies undertook covert action to assist runaways more directly through such means as the Underground Railroad and slave rescues that were often undertaken by Vigilance Committees. In addition to such noted slave rescues as that of Jane Johnson (c. 1814-22-1872), Pennsylvania also saw organized resistance in the form of the Christiana Riot. In this 1851 case, a Maryland slave owner acquired the necessary warrants to pursue suspected fugitives in Lancaster County but was killed during the pursuit. Five white and thirty-three Black people were charged with interfering with the Fugitive Slave Law, an infraction that carried a charge of treason. To some, these men were simply carrying out the promise of American freedom, but to others they were murderers who disregarded the nation’s laws. In the end, the prosecution failed to gain treason convictions, but public opinion remained split.

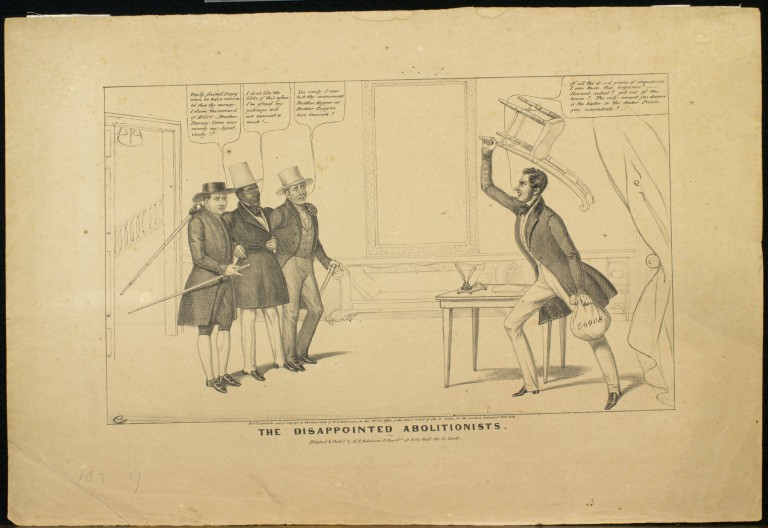

Support from abolitionists and free Black residents encouraged people in bondage to flee, but their presence angered many whites and led them to resent the free Black community. Historian Edward Raymond Turner, one of the first to focus on race relations in Pennsylvania, contended that, even while Pennsylvanians fought to help fugitives thwart the designs of their masters, most whites in the state held prejudiced views of Black persons, especially fugitive slaves, as inferior. Indeed, it was during this same period that Pennsylvanians supported the strongest state auxiliary to the American Colonization Society, a group that worked hard to send Black people to Africa.

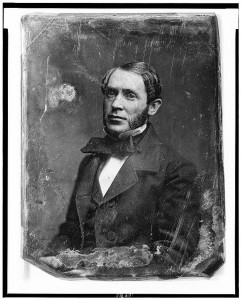

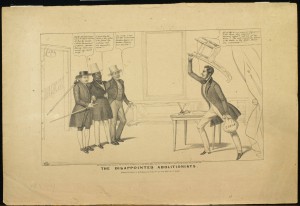

In Pennsylvania and New Jersey, a significant number of whites saw the fugitives, rather than the slave catchers, as the source of disruption and lawlessness. Historian James Gigantino has argued that New Jersey politicians consistently communicated “solidarity with southerners, a desire for law and order on the border, and for gradual approaches to abolition.” Historian David Smith found similar tensions in southeastern Pennsylvania, but he concluded that antislavery leaders like Thaddeus Stevens (1792-1868) found a way to chip away at slavery by focusing on individual kidnap victims and fugitives. In taking individual cases to court, they were able to appeal to some local whites on a personal level by humanizing accused fugitives while keeping with the PAS tradition of using legal action rather than the sweeping emotional appeals offered by those demanding an immediate end to slavery.

Rhetoric over the status of the new territories grew heated throughout the antebellum years, with opponents of slavery insisting that the new states exclude slavery in favor of a “free soil” system that allowed fair competition by preventing slaveholders from using their power, influence, and captive labor to dominate the new states. This political antislavery led to the creation of the Liberty Party in the 1840s, but, due partly to Stevens’s involvement, border abolitionists had developed a political antislavery that predated the emergence of that party and laid the groundwork for political abolition. As historian Richard Newman has shown, Pennsylvania abolitionists, free Black people, and the fugitives who sought their aid also created a “free soil” mindset even before the term was applied to the new territories in the years immediately preceding the Civil War. Historians agree that the fugitives forced the issue of slavery to remain at the forefront of border state politics, and their self-help efforts reinforced the work of abolitionists and free Black activists.

Beverly C. Tomek is the author of Pennsylvania Hall: A ‘Legal Lynching’ in the Shadow of the Liberty Bell (Oxford University Press, 2013) and Colonization and Its Discontents: Emancipation, Emigration, and Antislavery in Antebellum Pennsylvania (NYU Press, 2011). She earned a Ph.D. in history at the University of Houston and teaches at the University of Houston-Victoria. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Underground Railroad expert decodes songs that held practical advice for fleeing slaves (WHYY, October 15, 2014)

- Underground Railroad tour in Germantown offers 'hidden history' lessons (WHYY, October 14, 2014)

- Artifacts of NJ town run by freed slaves in New Jersey on display (WHYY, February 13, 2015)

- Delaware governor to pardon man who helped slaves escape (WHYY, October 21, 2015)

- Delaware inches closer to slavery apology (WHYY, December 7, 2015)

Links

- “The Liberation of Jane Johnson” (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- Quakers and Slavery: The Rescue of Jane Johnson (Bryn Mawr College)

- Quakers and Slavery - History Tour, Old City, Philadelphia (Arch Street Friends)

- From Fugitive Slaves to Free Americans (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The Underground Railroad and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)