Funerals and Burial Practices

By Karol Kovalovich Weaver | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

In the Philadelphia region, burial and funeral rituals have served to honor the dead and comfort the living. These practices have reflected shifting gender roles, new material and technological developments, and changing demographics. Until the mid-nineteenth century, women were the primary caretakers of the dead prior to burial, while male sextons interred bodies. By the late nineteenth century, embalming, undertaking, and funeral directing emerged as masculine occupations, changing funeral and burial practices both locally and nationally. Funeral and burial customs also developed in response to the arrival into the area of diverse populations.

Before the professionalization of mortuary practices, women known as layers-out of the dead, or shrouders, prepared the body. Layers honored the dead by washing, dressing, and grooming the body. Layers closed the deceased’s eyes and mouth, removed internal organs, blocked orifices, applied alcohol, and filled body cavities with charcoal to retard putrefaction. Their work allowed family members and friends to view their beloved with minimal revulsion. Female relatives and neighbors as well as women who offered their services for pay worked as layers-out of the dead.

Religious and ethnic traditions affected the arrangement of the corpse and the symbolic objects placed in the coffin and burial site. Christian burial tradition dictated that the body be positioned with the head to the west and with the hands resting on the thighs. Simplicity characterized Quaker practices: they used plain coffins, which were sometimes stacked on top of others, and, although proscribed, they marked graves with nondescript headstones. Anabaptists also valued plainness and modesty in their burial customs. Other Protestant denominations provided their adherents with more options. A person might choose to be laid to rest in the church graveyard, in a church vault, or, most prestigiously, in the church itself. Archaeological excavations in the yard of St. Paul’s on Third Street near Walnut Street uncovered burial vaults, evidence of the desire of the deceased, or their relatives, to highlight their socioeconomic standing. In the first half of the nineteenth century, African Americans adorned the bodies buried in the First African Baptist Church cemetery located on Vine Street between Eighth and Ninth Streets in Philadelphia with African ritual items and laid shoes—footwear for the journey to the African homeland—on several coffins. When the deceased lacked financial resources, social connections, or spiritual associations, they were buried without ceremony or coffins in mass graves in areas designated as “Strangers Grounds.” The most important of these was Southeast (later Washington) Square.

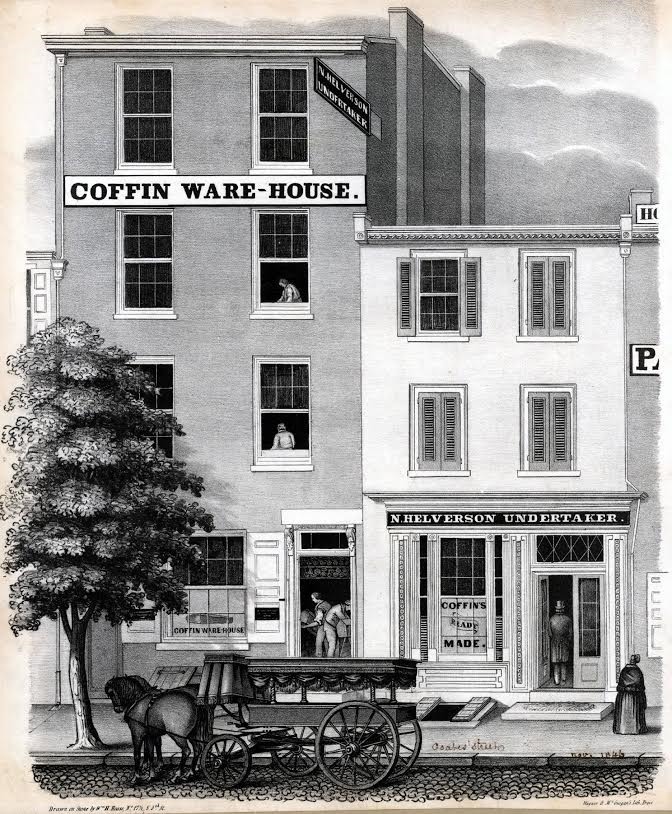

By the mid-nineteenth century, formally trained and licensed professionals, including undertakers and embalmers, increasingly assumed the task of caring for the dead. Undertakers orchestrated funerals and embalmers prepared bodies. Philadelphia city directories reveal that men who worked as undertakers and embalmers greatly outnumbered hired female shrouders. In 1867, Philadelphia had 125 male undertakers, one female undertaker, and only four female layers-out of the dead. Undertaking frequently was a family business.

The Civil War, industrial accidents, medical professionalization and specialization, and increasing dependence on hospitals and homes for the incurable contributed to these changes. The massive death toll of the Civil War was a boon to undertakers and embalmers, and the viewing of Abraham Lincoln’s embalmed body by thousands of Americans popularized the technique. Industrial accidents resulting in disfiguring deaths gave rise to new embalming specialties, specifically restorative art. With the growth of hospitals, fewer people died at home; subsequently, their corpses were no longer prepared or viewed there. In the second half of the nineteenth century, undertakers, now most often referred to as “funeral directors,” learned embalming or partnered with embalmers to establish a new profession. Some funeral directors dedicated their practices to specific ethnic and religious communities. Families who desired to show their love and respect for their deceased did so by patronizing these professionals.

Not only did the people who cared for the dead change, so did the vessels in which bodies were buried. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, coffins were often plain, hexagonal, pinch-toed boxes decorated with simple iron handles. Germantown was home to one of the nation’s oldest coffin producers, the workshop of Jacob Knorr. By the end of the nineteenth century, the casket replaced the coffin. Larger, more ornate, rectangular in shape, adorned with elaborate handles, and sometimes topped by a window through which the living viewed the dead, the “casket” was a receptacle that housed a precious treasure. The casket designated the deceased as a unique being, and its extravagance signified the dead’s real or desired class status.

Cremation also gained acceptance in the late nineteenth century. Fears about the spread of disease through improper burials convinced some Pennsylvanians to adopt cremation as a more sanitary option. The country’s first crematory, established in the western Pennsylvania town of Washington, led to the construction of other furnaces, including the state’s second crematory in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Reformers organized societies that promoted cremation instead of burial in both Philadelphia and Lancaster. The Philadelphia Cremation Society, established in 1886, built the city’s first crematorium, and the city Board of Health soon erected a second adjacent to the municipal hospital. New Jersey constructed its first crematoriums in the early twentieth century.

Demographic changes also affected the burial and funeral practices in the Greater Philadelphia region. Diverse ethnic groups brought varied customs. The Irish celebrated the wake, a vigil initially designed to ensure that the deceased was indeed dead. Characterized sometimes by rowdy fellowship, including drinking and joke telling, the wake ended with the sharing of a large meal with family and friends after the funeral mass. Jewish migrants to the region, like the Quakers, favored plain, wooden coffins without nails and introduced their seven-day mourning ritual of Shiva, observed when a loved one passed or married outside the faith. Many African Americans, who journeyed to Philadelphia during the Great Migration, chose to be buried in the South; their remains made their final journeys aboard trains. Arriving home, the bodies were picked up by southern Black funeral directors who prepared them for viewing. Italians who settled in South Philadelphia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries adapted funeral rituals from Italy to their urban neighborhoods. They melded Italian folk beliefs and practices intended to prevent the return of the deceased among the living with a desire for social status, spending lavish amounts on funerals, buying opulent caskets, large flower sprays, and impressive gravestones decorated with photographs of the deceased. To keep the dead from visiting those who remained, they tucked treats, such as cigarettes, into caskets. Family picnics and walks at cemeteries served to keep the deceased happy and provided the living the chance to experience a peaceful, natural setting, away from the hard streets of their South Philadelphia neighborhoods.

Among the most elaborate funerals were those for fallen police officers and firefighters, which broadened the definition of family to embrace fellow service members as well as biological kin. Hundreds of police officers or firefighters participated in these funerals honoring their comrades and highlighting the dangerous but essential work these men and women performed. The wearing of dress uniforms, the placing of mourning bands across badges and on vehicles for prescribed mourning periods, and the erection of end-of-watch memorials both honored the dead and brought comfort to the living.

By the turn of the twenty-first century, digital technology and the environmental movement were changing the region’s funeral practices. Family and friends, spread across the nation and around the globe, paid their respects to lost loved ones through online memorials that allowed viewers to see photographs of the deceased, offer condolences, and share memories. Those who sought greener burial and funeral options turned to home viewings, natural cemeteries such as Green Meadow Natural Burial Ground in Fountain Hill, Pennsylvania, and the enclosure of their remains in concrete balls deposited in the Atlantic Ocean and used to create coral reefs.

Professional, material, and social factors have influenced the development of funeral and burial practices in the Philadelphia region for centuries. Female layers gave way to male undertakers, coffins gave way to caskets, and cremation often replaced burial. And throughout, religious, economic, and ethnic diversity impacted the choices residents made about their final farewells and resting places.

Karol Kovalovich Weaver is the author of Medical Revolutionaries: The Enslaved Healers of Eighteenth-Century Saint Domingue (University of Illinois Press) and Medical Caregiving and Identity in Pennsylvania’s Anthracite Region, 1880–2000 (Penn State Press). Her third book project is titled Powerful Grief: American Women and the Politics of Death. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Changes in Pa. rules rankle some funeral directors (WHYY, May 15, 2012)

- Nameless in death, nine bodies exhumed in Pa. in hopes of unearthing identity (WHYY, September 26, 2016)

- Historic cemeteries struggle to return from decades of neglect (WHYY, November 15, 2016)

- In South Jersey, a familiar fight to save a historic African-American cemetery (WHYY, April 25, 2017)

Links

- Historic Philadelphia Burial Grounds Map (Philadelphia Archaeological Forum)

- Abraham Lincoln's Funeral Procession Through Philadelphia (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)

- Layers-out of the dead, The Philadelphia Directory, 1808 (Internet Archive)

- Philadelphia Police Memorial Museum

- Officer Down Memorial Page

- Morgue Workers Taking a Break (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Dr. LeMoyne, inventor of the first United States Crematory, in Washington, Pennsylvania (ExplorePAHistory.com)