Greek War for Independence

Essay

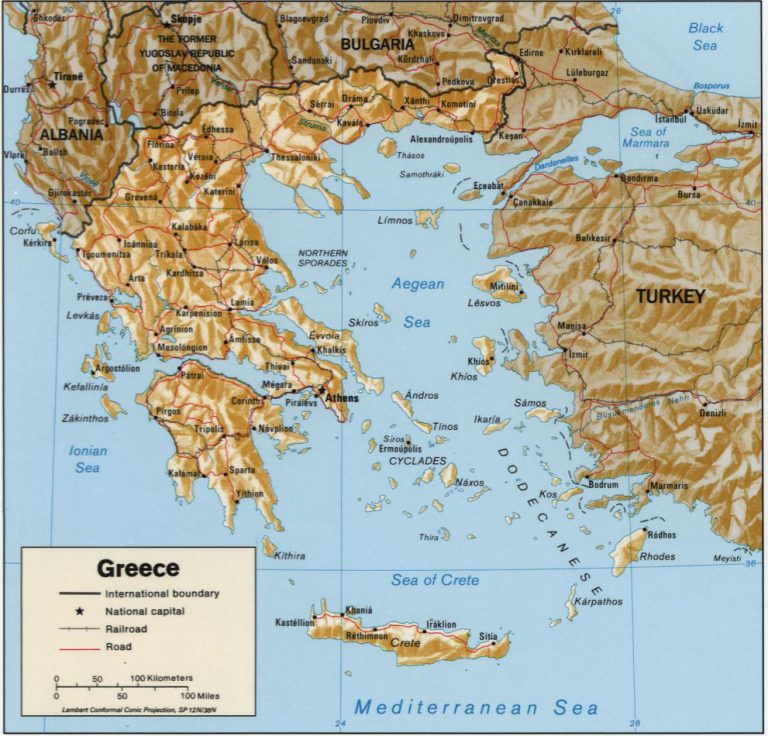

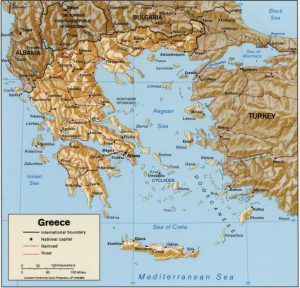

During the Greek War for Independence (1821-28), when the Greeks of the Morea (Peloponessus) rose in rebellion after almost four centuries of Ottoman rule, Philadelphians helped to arouse public sentiment and sympathy in favor of the Greeks, raised money and provisions to aid the cause, and lobbied their representatives to recognize Hellenic independence. In Philadelphia and elsewhere in the United States, philhellenes (lovers of Greek culture) sought to convince the American public that Greece, as the birthplace of western civilization, deserved to be resurrected as a free and democratic state. And as the inheritors of this tradition of liberty, Americans had a duty to help Greece reclaim its birthright.

Often styled the “Athens of America” for its cultural richness and taking its name from the Greek words for love (phileo) and brother (adelphos), Philadelphia proved to be well-suited to lend its moral and material support to the Greeks. By the time of the Greek revolution, Philadelphia was in the midst of its own Hellenic renaissance with the building of the Second Bank of the United States between 1818 and 1824. Modeled on the Parthenon, the Second Bank was regarded as the first truly Greek Revival building in the United States.

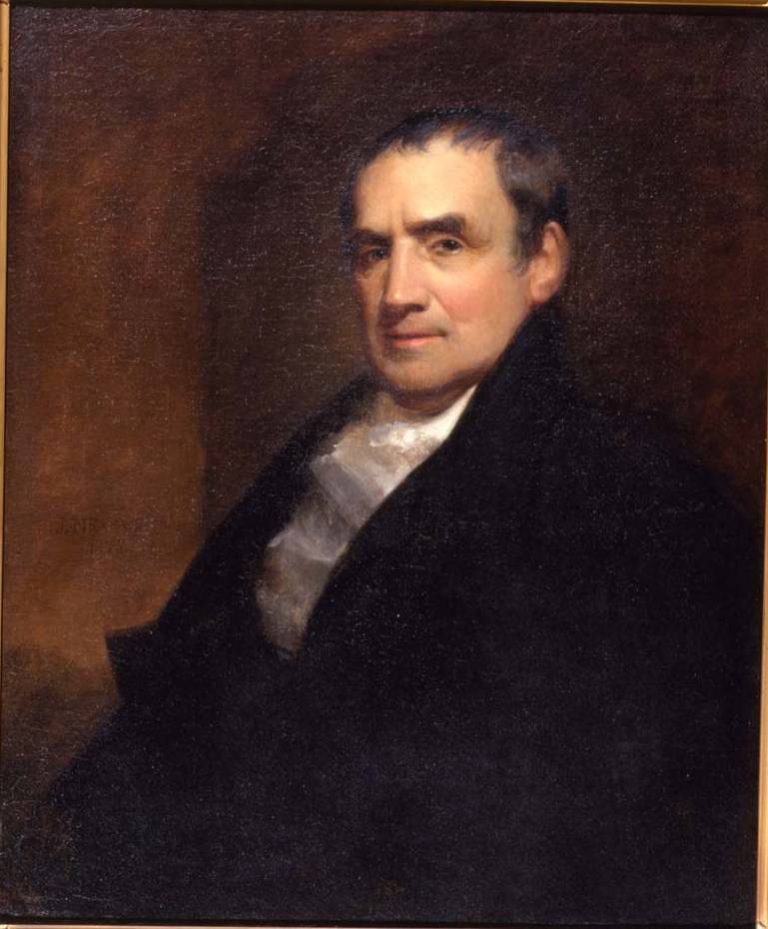

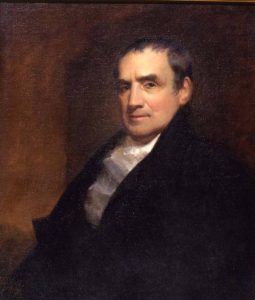

On December 11, 1823, several of Philadelphia’s most prominent citizens met at the Masonic Hall on Chestnut Street to form a committee to help the Greeks. Foremost among them was Mathew Carey (1760-1839), an Irish immigrant and publisher, who was elected committee secretary. Having immigrated to the United States in 1784 after fleeing political and religious persecution in Ireland, Carey found a strong kinship with those fighting for freedom in Greece. Carey had long been active in charitable work in Philadelphia. In the 1790s, he formed the Hibernian Society for the relief of Irish immigrants, and in 1829 he helped organize the Society for Bettering the Condition of the Poor. For the new committee to aid the Greeks, other members included Episcopal Bishop William White (1748-1836) as chairman; William Meredith (1799-1873), the president of Schuylkill Bank and future attorney general of Pennsylvania, as treasurer; Philadelphia Mayor Joseph Watson (1784-1841); George M. Dallas (1792-1864), future vice president of the United States under James K. Polk; Thomas M. Pettit (1797-1853), city solicitor and later deputy attorney general of Pennsylvania; prominent physician Nathaniel Chapman (1780-1853), future founding president of the American Medical Association; Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844), president of the Second Bank of the United States; local poet and playwright James N. Barker (1784-1858); and merchants and philanthropists Samuel Archer (1771-1839) and Paul Beck Jr. (1760-1844). Biddle had visited Greece in 1806, becoming only the second American to visit that country. He became a renowned patron and promoter of Greek culture and architecture in the United States.

A Nationwide Movement

Similar committees formed in almost every region of the United States. New York was the leading center, coordinating the collection of funds throughout the nation. Philadelphia’s failure to surpass New York was the result of strong Quaker objections. With a number of individuals reluctant to support measures that promised to aid military operations in Greece, the Philadelphia committee chose to act independently. Despite Quaker opposition, Philadelphia nonetheless came in second to New York in the amount raised, contributing $3,900 in aid.

A new relief campaign began in Philadelphia on December 16, 1826, after Carey became committee chairman. Instead of soliciting donations to support the Greek government’s military operations, Carey now sought to provide exclusively for the thousands of civilian refugees left homeless by the war and suffering from famine. Supporters no longer invoked the names of ancient philosophers or spoke of the past glories of Marathon and Thermopylae. The new emphasis on humanitarianism proved more successful among Philadelphians previously reluctant to finance the Greek war effort, which could be perceived as compromising U.S. neutrality.

The campaign raised funds with several theatrical performances and special benefit concerts, and clergymen and politicians delivered fiery sermons and spirited panegyrics while they took up collections. Several other committees around Pennsylvania remitted contributions to the Philadelphia group, building to a total of nearly $23,700 in aid. Chester County sent donations totaling $3,362; Pittsburgh reported $1,800 in collections; Delaware County donated $485; Bucks County added $485; Lancaster contributed $350; York sent $432; Montgomery reported $400; and North Cumberland, $500. Philadelphia also received donations from outside the state, from such places as Spartansburg, South Carolina, and Greenville, Kentucky.

The Philadelphia committee, like those in New York and Boston, purchased cargoes of food and clothing, which an American representative accompanied to Greece and distributed to the needy. Philadelphians sponsored two cargo ships, the Tontine ($13,856.40) and Levant ($8,547.18). In all, philhellenes in the United States financed eight ships and cargo valued at under $138,000. Some of the cargo did not reach its intended recipients, however. The Greek provisional government wrote the Philadelphia committee in May 1827 to express its gratitude but also to request that some of the supplies be appropriated to the soldiery instead of noncombatants. When the Tontine arrived, Greek authorities seized its cargo. Afterward, the U.S. frigate Constitution arrived to ensure the safety of future cargoes.

Greece Achieves Independence

The incident involving the Tontine and reports of Greek piracy may have adversely affected future subscriptions. On April 2, 1828, the Philadelphia committee officially folded its operation. By then the revolution in Greece was coming to a close. The destruction of the Turkish navy at the Battle of Navarino in October 1827 by a combined British, French, and Russian fleet assured a Greek victory. In May 1832, Greece was formally recognized as an independent nation. But this did not mean that efforts to assist the Greeks came to an end. After the revolution, religious outreach programs continued. In 1830, at the insistence of Bishop William White, the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society embarked on an ambitious plan to establish schools in Greece.

By separating relief from the political and military affairs of Greece, supporters succeeded in linking their movement to broader patterns of benevolent, religious, and humanitarian interests during the 1820s. In these years an unprecedented number of Americans joined together in a far-flung network of benevolent, charitable, and religiously-oriented organizations that aimed to spread personal, intellectual, and moral improvement. Reformers embarked on an array of crusades. As these humanitarians began to address the social problems at home, they naturally became drawn to helping alleviate similar hardships overseas. The Greek campaign plunged American benevolence into the international arena.

Angelo Repousis received his Ph.D. from Temple University and teaches there as an Adjunct Assistant Professor of History. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University