Liberty County

Essay

City and state politicians representing Northeast Philadelphia, deeply unsettled by the shifting economy and demographic makeup of the city in the 1980s, proposed seceding to create “Liberty County,” a separate, suburban municipality to ostensibly address taxpayers’ demands for improved municipal services. The primary impetus for such a radical step, however, was reaction to Philadelphia’s first African American mayor, W. Wilson Goode (b. 1938), whose election in 1983 further stoked racial anxieties throughout Northeast Philadelphia. Supporters of secession pressed for independence from the city throughout Goode’s two terms as mayor, but after his reelection in 1987 the movement diminished as many residents, refusing to acknowledge Goode’s municipal contributions to their neighborhoods because of his race, chose to move to the suburbs rather than continue the fight.

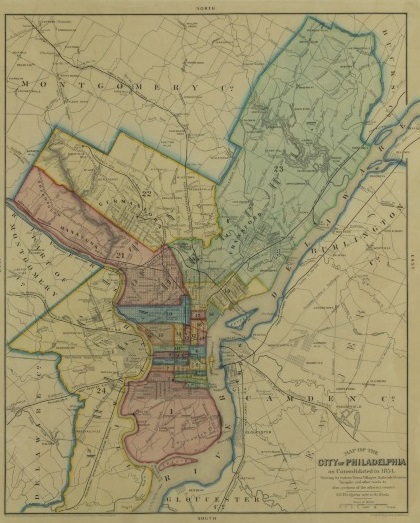

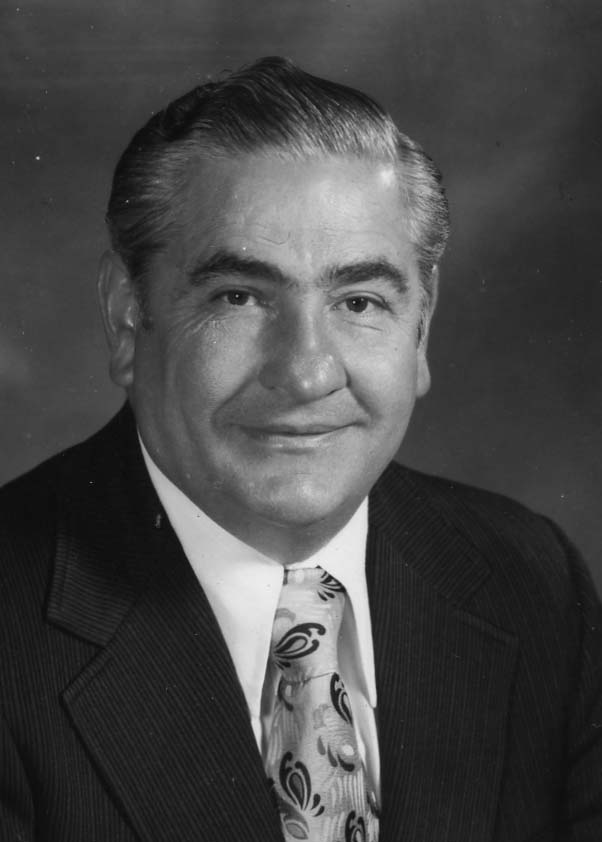

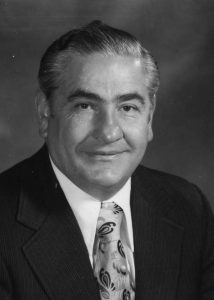

A rising political star in Philadelphia politics who had served as managing director for Mayor William Green (b. 1938), Goode campaigned throughout Northeast Philadelphia in an effort to convince skeptical white voters that he would improve municipal services if elected mayor. Residents remained hostile to Goode’s candidacy, however, largely because of his race. Shortly after his election, Frank “Hank” Salvatore (1922-2014), a Republican state representative from Far Northeast Philadelphia, submitted a bill to the Pennsylvania legislature proposing that Northeast Philadelphia secede from the city to become a separate entity to be known as Liberty County. Goode countered by working to establish an amicable relationship with business and civic organizations in the Northeast and promising in 1984 to build “a mini-City Hall” there. His efforts fell short, however, as Northeast city council representatives Joan Krajewski (1934-2013) and Brian O’Neill (b. 1949) remained skeptical of Goode’s intentions, eventually joining an emerging chorus of community activists who questioned whether the mayor could fulfill his promise to build a municipal services center.

In May 1985 relations between Goode and his Northeast constituents took a further turn for the worse. Following the tragically botched effort to remove the Black nationalist and anarcho-primitivist group MOVE from Osage Avenue in West Philadelphia on May 13, Northeast residents began to speak fearfully of the possibility that Goode might similarly resort to dropping explosives on their neighborhoods if they failed to comply with his executive authority. Even as the city launched a formal investigation into the mayor’s handling of the crisis, Hank Salvatore sought to capitalize on the mayor’s political misfortunes by demanding a concurrent state legislative inquiry about the mayor’s actions against MOVE and its compound. Not to be cowed, Goode rebuffed his white political and civic-minded critics and made good on his promise for a Northeast “mini-City Hall,” which opened at the Northeast Shopping Center at Roosevelt Boulevard and Welsh Road in September 1985.

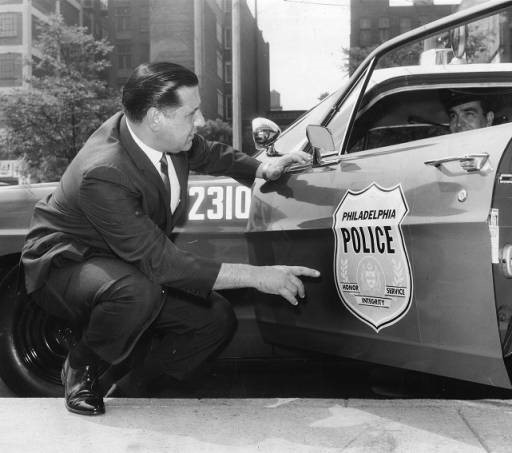

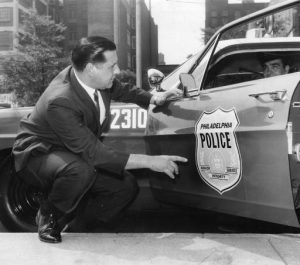

Goode’s action failed to alter the situation and animus against him in the Northeast peaked just months later in July 1986 during a municipal services strike that left piles of trash strewn on neighborhood sidewalks. Residents blamed the mayor for failing to resolve the crisis. With cries for Salvatore’s secession proposal still festering, the emergence of former mayor and police commissioner Frank Rizzo (1920-91) as a candidate once again for mayor further aggravated relations with the city. Labeled by supporters as a “Great White Hope,” Rizzo stormed Northeast neighborhoods, where he assured supporters that he would significantly improve city services if elected. By contrast, Goode, who had pledged color-blind governance in 1983, found little support in the Northeast during the 1987 campaign and increasingly courted African American voters in other parts of the city. While Goode ultimately prevailed over Rizzo to gain reelection–winning a significant number of Black voters but losing by large margins in Northeast Philadelphia–he was left governing a city that had failed to expunge its racial demons.

Resentful of Goode’s continued presence as mayor, Salvatore rallied those who supported his secessionist stance one last time by openly threatening again in February 1988 to create a separate, suburban entity, Liberty County, through state legislation. His action drew praise from some Northeast residents, who called him a latter-day “Patrick Henry” who would save the Northeast from the perceived tyranny of “King Wilson I.” But his plan lacked the same widespread community support it had initially corralled during the mid-1980s. Liberty County became little more than a fantasy to its white supporters, who slowly left the city for better housing opportunities and municipal services in the nearby suburbs during the 1990s and early 2000s. Salvatore’s supporters periodically reproposed his Liberty County idea in local newspapers throughout the Northeast , but lacked sufficient political support in their communities to make it a viable initiative.

Matthew Smalarz teaches history at Manor College in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, where he serves as the History and Social Sciences Coordinator and received the Outstanding Educator of the Year Award for the 2016-2017 academic year. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Crossing cultural lines to solve everyday troubles in Northeast Philadelphia (WHYY, June 8, 2011)

- Philadelphia zoning board denies methadone clinic for northeast neighborhood (WHYY, March 14, 2012)

- How a poverty study speaks to all races in Philadelphia (WHYY, July 29, 2013)

- Been there, do this: Mayor Wilson Goode Sr. talks leadership and vision for the city's future (NewsWorks, February 11, 2015)