Lincoln Drive

Essay

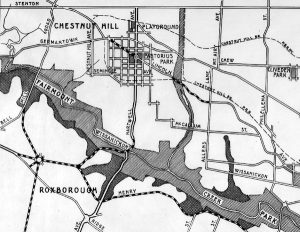

The 4.1 miles of Lincoln Drive that link Philadelphia’s northwest neighborhoods to Center City was built in three distinct segments over the course of five decades in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At its south end, a winding mid-nineteenth-century section along the Wissahickon Creek was originally constructed to provide access to water-powered industrial mills. A middle, City Beautiful-era section, was constructed on top of the channelized and buried Monoshone Creek. And at its north end, a discontinuous section was built to facilitate residential development of the Chestnut Hill neighborhood in the early twentieth century. Lincoln Drive’s twisting alignment and complicated character—a single roadway that functions as both a local street and a major arterial—reflect its hydrological origins and gradual evolution from commercial road to parkway to high-volume commuter route.

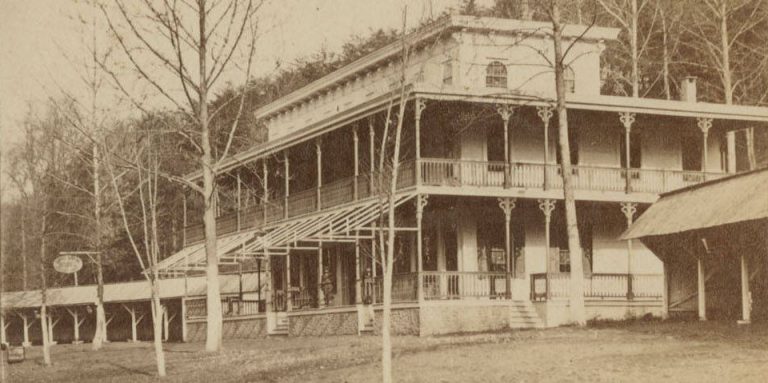

The first section of Lincoln Drive was a mile-and-a-half-long private toll road known as the Wissahickon Turnpike. Completed in 1856, it ran along the Wissahickon Creek between its confluence with the Schuylkill River, in the East Falls neighborhood, and Rittenhouse Town (also referred to as “Rittenhousetown” in many early sources), a small settlement of mills and residences in the Germantown neighborhood. This earliest section of the road provided access to paper, grist, fulling, saw, and powder mills that contributed to Philadelphia’s early industrial development. Inns, such as the Maple Spring Hotel, quickly sprang up along the turnpike to lodge and feed people traveling into and out of the city.

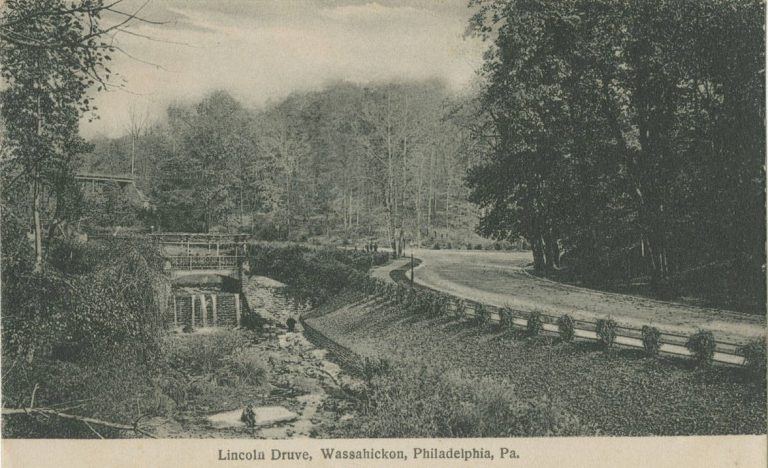

This first incarnation of Lincoln Drive was short-lived, however. Most of the mills along the Wissahickon Turnpike were gone within thirty years of the road’s construction. The city’s Fairmount Park Commission took title to lands in the Wissahickon River Valley in 1869 and 1870 and—to eliminate industrial discharges and protect water quality downstream—razed the mills. Still, the road, renamed Wissahickon Lane in the mid-1880s, remained open to provide access to the city’s growing park system and to the southern end of Germantown.

In the late 1890s, Wissahickon Lane was extended one and a half miles from Rittenhouse Town into the Mount Airy neighborhood. The combined length—the newly constructed section and the older mid-nineteenth century section—was given a new identity by being christened “Lincoln” in honor of the sixteenth U.S. president, though the road was known as Lincoln Avenue until an official name change to Lincoln Drive in 1931.

A Fortuitous Convergence

This extension of Wissahickon Lane and its renaming resulted from the concurrence of an exceptional opportunity and a growing demand. The opportunity was provided by the construction of a modern sewer system by the Public Works Department. The growing demand was for good roads due to booming sales of the first modern automobiles to wealthy residents of Mount Airy and Chestnut Hill.

Philadelphia’s Public Works Department, in just one example of projects occurring across the city in the 1890s, channelized and buried in sewer pipes much of a small tributary of the Wissahickon called Monoshone Creek (also known as “Paper Mill Run” on some early maps). Then, between 1900 and 1909, the underground sewer was extended into Chestnut Hill and the branch’s entire length from Germantown to Chestnut Hill became known as the “Lincoln Avenue Interceptor.” This buried stream provided the alignment on which Lincoln Drive was built. (Streams and creeks elsewhere in the city met a similar fate, many of them with names still familiar today because of the roads that were constructed on top of them: Aramingo, Wingohocking, and Tacony, to name a few.)

This extension of Lincoln Drive provided a second major roadway connection to Center City. The other was Germantown Avenue, a historic, centuries-old road connecting Philadelphia to Chestnut Hill and to towns and cities to the north and west, including Reading, Allentown, and Bethlehem.

The covering of Monoshone Creek made possible the creation of Lincoln Drive, providing a routing and serving the functional and social interests of wealthy northwest neighborhood residents. By the early 1900s Germantown Avenue, still cobblestoned for much of its length, accommodated a busy electric trolley route, making it an inconvenient, uncomfortable, and slow route to use in early cars. Not only did the newly constructed Lincoln Avenue provide a faster route to Center City, it was built to be an aesthetically pleasing parkway in the City Beautiful tradition, an ideal road on which to drive. It complemented the two rail lines already serving the northwestern suburbs.

City Beautiful Influences

This conception of Lincoln Avenue in the 1910s and 1920s—as a beautifully designed parkway in keeping with the principles of the City Beautiful movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—had a lasting impact on adjacent land uses into the 1940s and 1950s. A few commercial properties were established along Lincoln Avenue/Drive, including gas stations and automotive garages. But many residents criticized them for being unsightly and out of keeping with the intent of the roadway. Their opposition succeeded in leading City Council to pass an ordinance in 1930 to prohibit additional filling stations on Lincoln Drive between Mount Airy Avenue and Sedgwick Street. The ordinance was overturned by a Court of Common Pleas the following year, however, because it was deemed an unreasonable and discriminatory prohibition on competition (three gasoline stations already existed nearby). The gas stations remained, but only a few commercial businesses joined them in the following decades and the roadway maintained its primarily residential nature.

Even as the middle section of Lincoln Avenue was being constructed, developers, politicians, and city planners envisioned the extension of the road into Chestnut Hill. There it would connect to Bethlehem Pike and to a proposed bridge over the Wissahickon to link Chestnut Hill to Philadelphia’s Roxborough neighborhood and Main Line communities to the west. Pennsylvania State Senator George Woodward (1863-1952), son-in-law of Chestnut Hill developer Henry Howard Houston (1820-95), strongly advocated for the road and bridge investments. The Houston and Woodward families had substantial land holdings in northwest Philadelphia on both sides of the Wissahickon Creek, and faster and easier access to them would have significantly increased their value.

The extension was quickly initiated in the early 1900s, but in an incomplete and discontinuous manner that left a half-mile gap in the road between Allens Lane in Mount Airy and Cresheim Valley Road in Chestnut Hill and saw the road end at Abington Avenue, a half mile short of its envisioned connection to Bethlehem Pike. Although filling in the gaps remained a priority for many in Chestnut Hill, the Great Depression of the 1930s and the war years that followed left the proposals unfunded and unrealized.

In the 1950s, automobile ownership rose quickly and traffic volumes on Lincoln Drive increased rapidly, as they did on roads and highways throughout the city, the region, and the United States. Following public hearings organized by the city’s Board of Surveyors, some roadway modifications to increase vehicle capacity on Lincoln Drive were implemented, such as the widening of the drive from two to four lanes. But eventually, residents and business owners who had come to value the neighborhood’s reputation for exclusivity and quiet argued for keeping expansions to travel corridors in Chestnut Hill out of the heart of the neighborhood. In the early 1960s, those arguments won out and city planners dropped proposals for any additional work on Lincoln Drive from official city documents. The northern segment of Lincoln Drive remained a discontinuous and less-traveled section of the road.

Rising Car Ownership

By the turn of the twenty-first century, rising car ownership rates and ongoing development in Mount Airy and Chestnut Hill resulted in another change in the character of Lincoln Drive. By 2000, it had become a major route for commuters traveling from the northwestern neighborhoods of Philadelphia to Center City via the drive’s southern end, where motorists continued along the Schuylkill River via Interstate 76 (on the west bank) or Kelly Drive (on the east). Traffic volumes rose to a high level: tens of thousands of cars used the southernmost section of Lincoln Drive every day, with volumes tapering down to the low single-digit thousands in the northernmost section in Chestnut Hill. Because of the drive’s traffic volumes, narrow lanes, and winding route, buses and large commercial trucks were prohibited from using it.

While Lincoln Drive did not match the traffic volumes or crash counts of Philadelphia’s most dangerous roadways, such as Roosevelt Boulevard in the city’s Northeast, it developed a reputation for being a risky route. Commuters regularly traveled at double its posted 25 mph speed limit. And serious accidents, some causing major injuries and fatalities, occurred regularly, such as the 1982 crash on Lincoln Drive near Rittenhouse Street that left Philadelphia native and R&B singer Teddy Pendergrass (1950-2010) a paraplegic.

None of the 4.1 miles of Lincoln Drive existed before the mid-1850s, nearly two centuries after the founding of the city of Philadelphia by William Penn in 1682, but the eventual road and its alignment became reminders of the economic, infrastructure, and natural histories of the city. The beauty of the southern section’s setting along the Wissahickon Creek was impossible to miss, the history preserved in the Rittenhouse Town Historic District evoked the city’s industrial past, and the leafy early twentieth century neighborhoods of Mount Airy and Chestnut Hill illustrated the connection between residential development and investments in transportation infrastructure.

Bradley Flamm is the Director of Sustainability at West Chester University, an academic who has taught at Temple University and the University of Pennsylvania, a transportation planner, and a resident of Northwest Philadelphia. He is grateful to the Philadelphia Streets Department’s Michael Carroll and Frank Morelli, the Philadelphia Free Library’s Alina Josan, and the Philadelphia City Planning Commission’s David Schaaf for their assistance in researching this article. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Design set for Lincoln Drive gateway markers (WHYY, November 18, 2010)

- Lincoln Drive gateway project moves closer to completion (WHYY, October 15, 2012)

- Councilwoman Bass pushes for Lincoln Drive red-light cameras (WHYY, February 21, 2013)

- Lincoln Drive gateway project gets financial boost (WHYY, April 17, 2014)

- City grant to enable completion of Lincoln Drive gateway project (WHYY, August 10, 2015)

- Putting the brakes on Lincoln Drive's Raceway (PlanPhilly via WHYY, May 25, 2018)

Links

- Traveling Lincoln Drive (YouTube)

- Historic RittenhouseTown

- Germantown (VisitPhilly.com)

- Germantown Historical Society

- Chestnut Hill (chestnuthillpa.com)

- Lincoln Drive is called "Dead Man's Gulch" for a reason (Chestnut Hill Local)

- Main Sewerage Systems of Philadelphia, 1902, showing Lincoln Avenue Interceptor (Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network)

- Philadelphia Land Use Map, 1942 (Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network)