Locomotive Manufacturing

By John Hepp

Essay

For over one hundred and twenty years, railway locomotives were built in Greater Philadelphia. From the pioneering manufacturers of steam locomotives in the Spring Garden section of the city in the 1830s to the sprawling plant of the Baldwin Locomotive Works in Delaware County in the twentieth century, the products, the companies, and the buildings were archetypes of Philadelphia’s industrial might at its manufacturing peak. Baldwin Locomotive became the largest producer of steam railway locomotives in the United States. By the mid twentieth century, however, even Baldwin could no longer compete in the world market, which had shifted to diesel and electric locomotives.

The rise, dominance, and decline of locomotive manufacturing in the region had two complementary contexts, one local, the other transnational. In the late 1820s American railroads imported steam locomotives from Britain and, because the locomotives had to be partially disassembled for shipping, employed local artisans to put them back together. Because these imported locomotives were expensive and often too heavy and rigid for the poorly constructed track used in the United States, engineering firms on the East Coast quickly began to build local alternatives. In Philadelphia, entrepreneurs drew on the city’s broad engineering base and its skilled workforce to adapt the British technology.

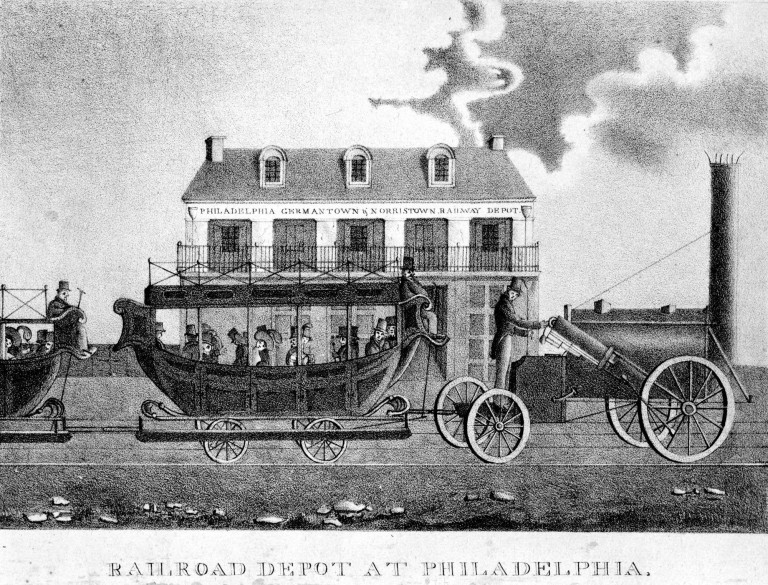

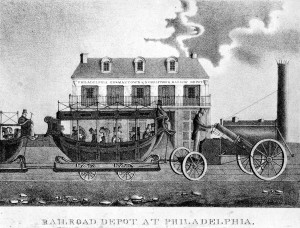

This first phase of locomotive building in Philadelphia lasted from the 1830s to the American Civil War and consisted of a variety of small-scale enterprises that tended to have difficulty surviving economic downturns, such as the Panic of 1837. In 1830, the American Steam Carriage Company was founded in Philadelphia and manufactured its first locomotive the next year. It failed. In 1831, Matthias W. Baldwin (1795-1866), a Philadelphia jeweler and machine maker, built a working scale model of one of these British imports for Peale’s Philadelphia Museum. That same year, he reassembled the English locomotives constructed for the New Castle and Frenchtown Turnpike and Rail Road, Delaware’s first railway, and learned still more about the new technology. In 1832, Long & Norris, a successor to American Steam Carriage, and Baldwin built successful locomotives for the Philadelphia, Germantown & Norristown Railroad, the first line to open in the city.

Norris Locomotive Works

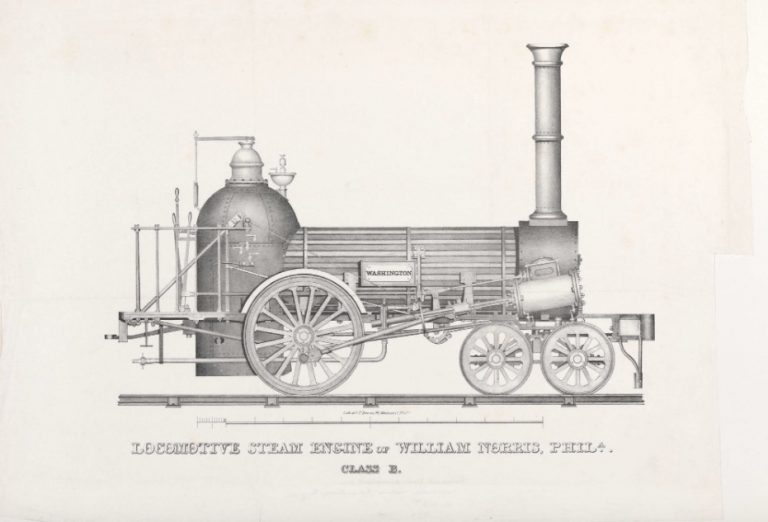

During this period the most successful builder in the city was the Norris Locomotive Works (the successor to Long & Norris, which operated under various names and differing partnerships). Norris produced nearly one thousand locomotives between 1834 and its closure in 1866 or 1867. The firm achieved success through engineering innovations (it substituted a movable truck or bogie for the standard fixed front axle on English locomotives, which worked better on the poor American track) and by generating publicity (on July 10, 1836, it operated a steam locomotive up the steep rope-worked inclined plane in West Philadelphia on the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad). Its designs became so popular that it became the first American exporter of locomotives. By 1840, 30 percent of the firm’s production went to foreign markets. Norris locomotives operated in England, France, Prussia, Austria, Saxony, Belgium, Italy, Canada, Cuba, and Colombia. By the 1850s, Norris was the largest locomotive builder in the United States, but it closed shortly after the Civil War during a downturn in demand for steam locomotives.

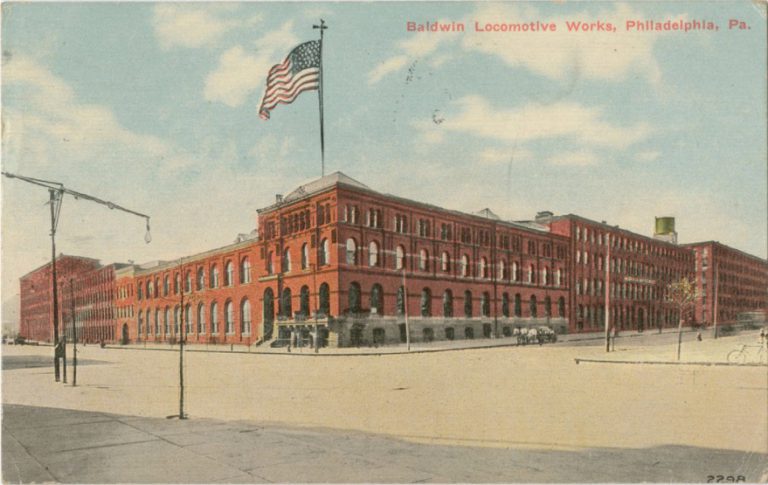

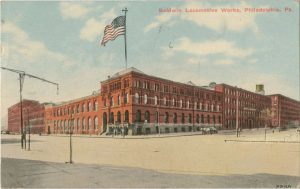

The second phase of railway locomotive production lasted from the end of the Civil War to the 1930s, a period when Philadelphia’s Baldwin Locomotive Works dominated the industry nationwide. With a plant located near the Norris Locomotive Works in the city’s Spring Garden section, in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s, Baldwin, although less innovative than Norris, produced higher-quality products. This, combined with innovations in financing, allowed Baldwin to thrive in the second half of the nineteenth century. By 1870 (four years after the death of its founder), the Baldwin Locomotive Works was by far the largest producer of steam locomotives in the United States and one of the largest manufacturers in the world. It, like Norris earlier, also exported its products worldwide. The peak of Baldwin’s production in Philadelphia came between 1898 and 1906, before railway regulation under the federal Hepburn Act (and the Panic of 1907) slowed demand for locomotives nationally. In 1906 alone, Baldwin produced 2,666 steam locomotives and employed more than eighteen thousand workers. Although the locomotive manufacturers did not know it at the time, increased regulation, two world wars, a Great Depression, and technological change would mean that demand for steam locomotives would never again reach this high point.

In the early twentieth century, as part of the City Beautiful Movement, Philadelphia and other American cities sought to relocate large-scale manufacturers like Baldwin away from central business districts and their peripheries. At the same time, Baldwin’s management desired a new and enlarged plant. The company acquired a large tract of land in suburban Eddystone, Delaware County, and slowly transferred all production there, completing the move by 1928. Constructed on a grand scale, the facility at Eddystone never operated at more than one-third of its capacity.

Challenges of New Technology

From the 1930s through 1956, Baldwin survived as not only the sole locomotive builder in Philadelphia but also as just one of a handful nationwide. Two technological changes in the first half of the twentieth century in the American railroad industry combined to decrease the demand for steam locomotives from Baldwin and its competitors. First came the electrification of commuter lines in New York and Philadelphia in the first three decades of the century. This eventually encouraged one of the railroads–the Pennsylvania–to electrify its busy main lines between New York, Washington, and Harrisburg. Then, although railroad electrification slowed, the development of diesel locomotives accelerated. First used in limited applications in the 1920s, by the end of the 1930s diesels operated as switch engines and on prestige passenger services, and by the 1940s were replacing steam locomotives in general service on most American railroads. Although more expensive than steam locomotives to purchase, diesels were cheaper and more efficient to operate.

As late as 1937, Baldwin’s management thought its future depended on the production of steam locomotives, despite changing technology. The next year, when Baldwin emerged from its 1935 bankruptcy with new management, it finally began to develop the newer diesel locomotives on a much larger scale.

During the Second World War, Baldwin continued to produce steam locomotives for both the United States and abroad and built tanks for the military at its massive Eddystone works. However, the War Production Board authorized Baldwin’s main competitors–the Electro-Motive Division of General Motors of La Grange, Illinois, and the American Locomotive Company (Alco) based in Schenectady, New York–to build diesels. This meant that Baldwin entered the postwar market in a weaker position.

After the Second World War, Baldwin introduced a full line of diesel locomotives and merged with a smaller locomotive builder to form Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton in 1950. Despite continual improvements in the products, the company’s sales remained well behind General Motors and Alco. In 1956, when the usually dependable Pennsylvania Railroad decided to place a large order with General Motors instead of Baldwin, the company ended the production of locomotives, although it continued to make construction equipment until around 1970. Baldwin had built over seventy thousand steam, electric, and diesel locomotives since 1832. With the closure of the once-massive Eddystone plant, locomotive production ceased in the greater Philadelphia area after 125 years.

Baldwin’s failed conversion to diesel production can be explained in part by the company’s late realization of the importance of the technological change, a policy offering custom-designed units in addition to a standard line, and its use of nonstandard technology (for example, electrical equipment made by Westinghouse instead of GE and, initially, its own form of multiple-unit control). On a global scale, however, none of the major steam locomotive builders that dominated the world market in the early twentieth century successfully made the transition to the construction of diesel and electric locomotives in the twenty-first. The new era simply required technology and skills that differed from steam locomotives. Baldwin, and with it the Philadelphia region’s role in locomotive manufacturing, became a casualty of massive industrial change in the second half of the twentieth century.

John Hepp is Associate Professor of History at Wilkes University in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, and he teaches American urban and cultural history with an emphasis on the period 1800 to 1940. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Along The City Branch, The Forgotten Norris Locomotive Works (Hidden City Philadelphia

- Locomotive Steam Engine of William Norris, Philadelphia (Internet Archive)

- Baldwin Locomotive Works (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Baldwin Locomotive Works Engine Specifications, 1869-1938 (Southern Methodist University Libraries)

- Baldwin Locomotive Works #26 (Steamtown National Historic Site)

- Norris Locomotive Works (Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network)

- The Railroad in Pennsylvania (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Friends of Matthias Baldwin Park