Mason-Dixon Line

Essay

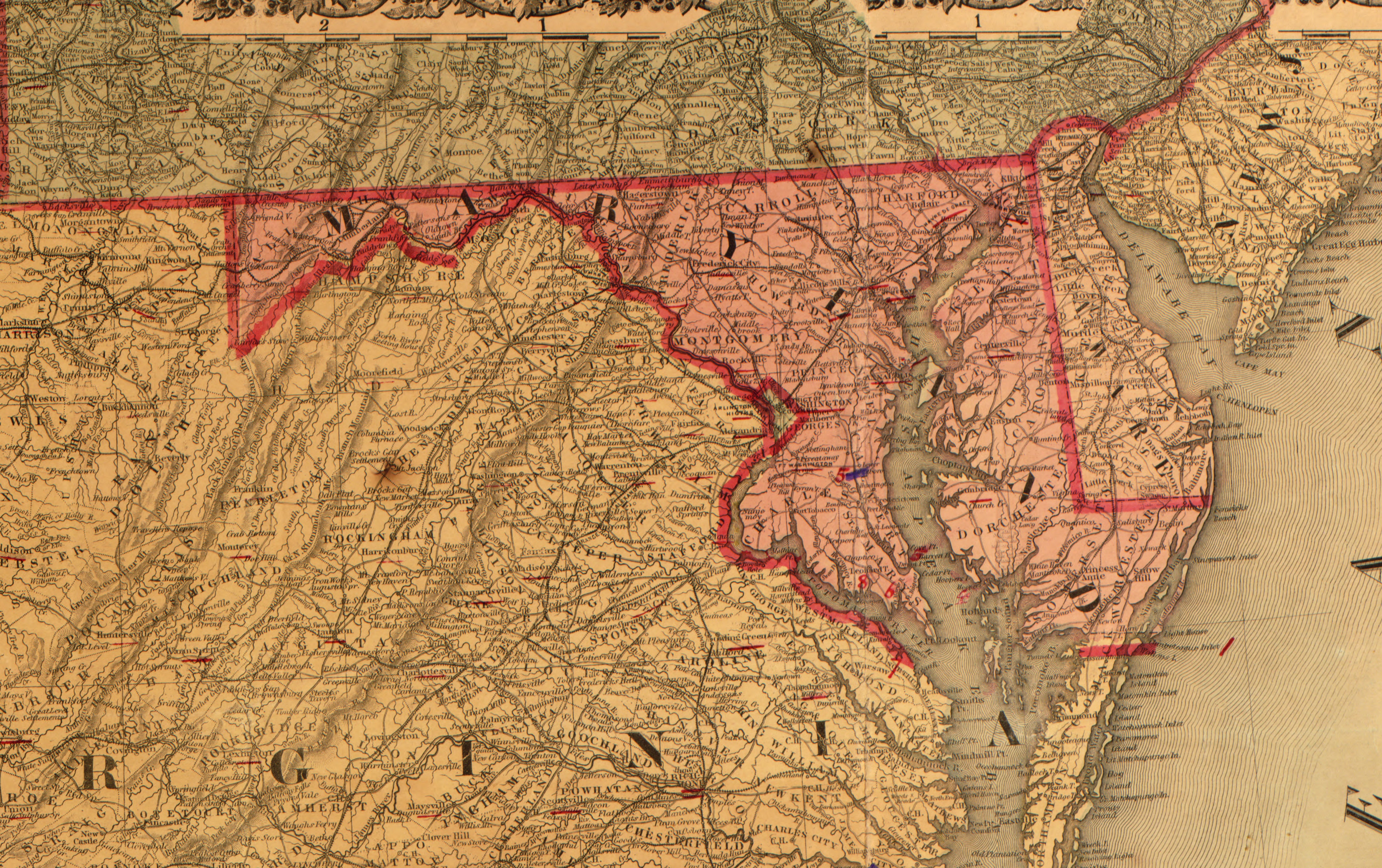

The Mason-Dixon Line, which settled a border dispute dating back to the founding of Philadelphia, is the southern boundary of Pennsylvania. Originally surveyed by Englishmen Charles Mason (1728-86) and Jeremiah Dixon (1733-79), the line separates Pennsylvania from Maryland and West Virginia along the 39º43ˊ N. parallel and bounds Delaware along an arc that extends from Maryland to the Delaware River. During the nineteenth century the line became a symbolic boundary between the southern and northern United States.

The territorial dispute between Maryland and Pennsylvania began immediately after King Charles II (1630-1685) gave William Penn (1644-1718) a charter to settle the lands between New York and Maryland in 1681. The charter set Pennsylvania’s southern boundary at the fortieth parallel, but the proprietors of both Maryland and Pennsylvania hoped to take advantage of the charter’s ambiguities. Pennsylvanians tried to push the boundary farther south and gain a port on the headwaters of the Chesapeake Bay. Marylanders contended that because Philadelphia is below the fortieth parallel, the city should actually be in Maryland.

In 1732 the British Board of Trade set the boundary about fifteen miles south of Philadelphia, though attempts to survey this line were abortive. Colonists on both sides forced the issue by settling on disputed lands and these perceived incursions, many of which were instigated by Marylander Thomas Cresap (1702-90), led to violence. In 1750, commissioners from both colonies agreed to run a border according to the 1732 agreement and, after struggling to conduct an accurate survey in the early 1760s, asked England’s Astronomer Royal for help. He sent Mason and Dixon.

Mason and Dixon arrived in Philadelphia in November 1763 while Pennsylvania was caught up in a cycle of increasingly racialized atrocities between whites and Natives, including the Paxton Boys’ massacre. Using state-of-the-art astronomical apparatus, Mason and Dixon surveyed borders between Delaware, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. In 1767, with the help of Iroquois guides, Mason and Dixon tried to extend their line west of the Royal Proclamation Line, which British officials had created in 1763 to regulate the expansion of white colonists into Indian lands across the Appalachian Mountains. But the threat of violence from Delaware Indians, who were then disputing Pennsylvanians’ and Iroquois claims to their territory, forced the expedition to turn back. In 1784, astronomers Andrew Ellicott (1754-1820) and David Rittenhouse (1732-96) ran the boundary to its intended endpoint—five degrees west of the Delaware River.

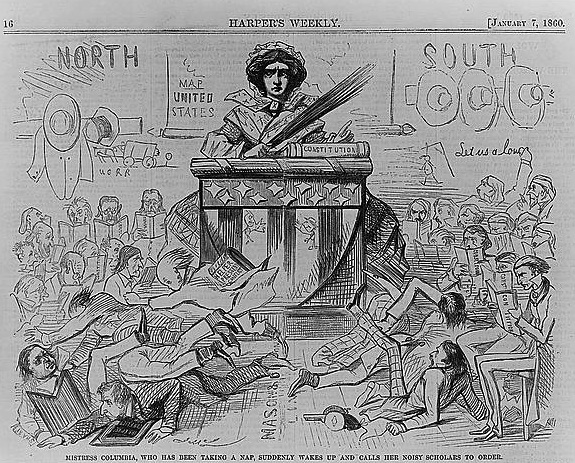

During the antebellum era, Americans began to identify the Mason-Dixon Line as delineating the northern and southern sections of the United States. But the line was never a clear boundary between a world where slavery ruled and one where freedom rang. Various forms of free and coerced labor existed along both sides of the line and southern slave owners maintained the legal right to recover enslaved Blacks who fled north of the 39º43ˊ parallel. Although many whites in Maryland, Delaware, and even Philadelphia sought to preserve racial slavery, the proximity of the line and the freedom it promised to runaway slaves forced planters in Maryland and Delaware to experiment with a wide variety of labor regimes. By 1860, large landowners in Maryland and Delaware had become far less dependent on slave labor than those in the Lower South and, ultimately, unwilling to join the confederacy, a crucial factor in the North’s eventual victory. For many Americans, the line has remained the iconic boundary between Northern and Southern cultures.

Cameron B. Strang is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Nevada, Reno. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Surveyors Historical Society

- Social Media: How Mason and Dixon would have looked on Twitter. (Twitter.com)

- Playing with Museum Representations of 18th-Century American Encounters (On Display Blog, October 25, 2014)

- Commentary: Preserving Mason-Dixon's milestones, history (Philadelphia Inquirer, May 24, 2016)