Mennonites

Essay

Philadelphia offered seventeenth-century Mennonite immigrants a gateway to the New World and their first permanent settlement in what would become the United States. Despite decades of migration to other parts of the country, Mennonites not only persisted in the city but also grew and diversified. By the early years of the twenty-first century, Mennonites in the greater Philadelphia region worshipped in eleven languages, reflecting the ethnic and racial diversity of the city itself.

Mennonites trace their religious roots to sixteenth-century Anabaptism, the so-called radical wing of Europe’s Protestant Reformation. On the continent, Mennonites and other Anabaptists distinguished themselves by practicing adult (rather than infant) baptism and by refusing to participate in violence, especially warfare. Persecuted in Europe for their convictions, many Mennonites emigrated to North America in the last half of the seventeenth century.

Hoping to avoid the political and religious sanctions they had experienced in their homelands, Mennonites in North America developed an identity as “the quiet in the land” by distancing themselves from the surrounding culture in visible ways. They opposed voting and holding public office, practiced nonviolence by refusing to join the military, required members to wear distinctive clothing (often called “plain dress”), and maintained strict disciplinary procedures for those who deviated from church expectations. Such social, political, and religious separatism enabled Mennonites to preserve their ethnic identity and Old World convictions in the new American setting.

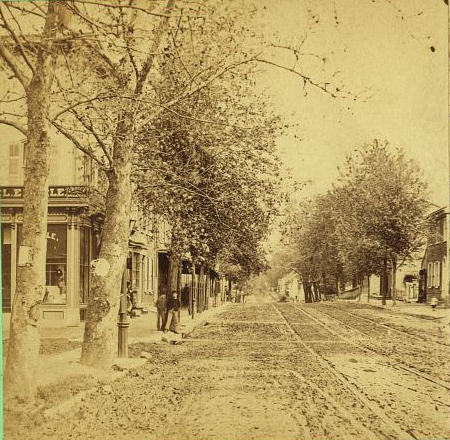

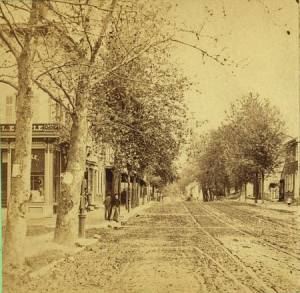

The first Mennonites to establish a permanent settlement in North America arrived in Philadelphia in October 1683. Most were of Dutch ethnic origin; a second wave, mostly Swiss, arrived in the early eighteenth century. Invited to the city by its Quaker founder, William Penn, the original immigrants settled in Germantown, then a small village about six miles north of the city (subsequently incorporated into Philadelphia in 1854). For a time, Mennonites worshiped with German Quakers, who constituted the majority population in the village. Some even converted to Quakerism; among these converts were three men who, in 1688, joined with a Lutheran Pietist to write the first protest against slavery in America, known as the Germantown Protest. In 1690, Mennonites established their own separate meeting for worship. In 1708, the congregation held its first baptism and communion service in a building constructed the same year and considered the oldest still-standing Mennonite meetinghouse in America.

Most Settled in the Hinterlands

Yet, while the city served as a port of entry for most Mennonite immigrants of Dutch and Swiss-German ancestry coming to America in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, few settled there. Most moved beyond Philadelphia to establish farming communities in places such as Franconia Township and Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. They believed that rural settlements would allow them to better preserve their distinctive practices and group identity. Thus, by 1820, some four thousand Mennonites and two hundred Amish, a closely related group, had settled in eastern Pennsylvania. Between 1817 and 1860, many Mennonites followed broader patterns of American migration and moved west, establishing settlements in Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Iowa. By the dawn of the twentieth century Mennonites had formed communities as far as Kansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Texas, Oregon, and California.

During this period of Mennonite migration and resettlement in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a variety of forces—religious, economic, and social—began to change Mennonite faith and practice. Cities, including Philadelphia, played a key role in these transformations. For instance, beginning in the 1830s and 1840s, some Dutch- and German-speaking Mennonites embraced the experiential faith of English-speaking evangelical Protestants, as well as their practices of revivalism, religious education, and missionary activity. These practices ultimately drew some Mennonites into major American cities, including Philadelphia, in hopes of finding converts to Christianity. Yet many of these new converts did not share Mennonites’ Dutch or Swiss-German ethnicity, nor their separatist beliefs, forcing would-be missionaries to adapt Mennonite faith to new contexts. These adaptations laid the groundwork for major changes to Mennonite faith and practice in the mid-twentieth century.

Additionally, during and after the American Civil War, changes in industry, transportation, and communication also propelled some entrepreneurial Mennonites into cities in search of new economic opportunity. Working and living in the urban crucible compelled some Mennonites to conform to the pressures of assimilation, including the pressure to speak English rather than German or Dutch.

Later, in the years following World War I, the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to northern cities and towns also challenged Mennonite theology and practice. In Philadelphia, African Americans felt drawn to Mennonites’ simple faith and the sense of family-like community they felt in worship services. Yet they balked at countercultural practices such as plain dress, especially because church members and leaders often failed to counter American society’s notions about racial hierarchy and segregation.

Separation of African Americans

For example, Philadelphia Mennonites contributed to the racial segregation that accompanied the migration of African Americans into the city in the interwar period. In the early 1930s, several African Americans began to attend services at the Mennonite mission near Norris Square in the Kensington neighborhood. Within a year, amid fears of racial mixing, mission leaders approved a petition to start a separate congregation for these new African American attendees. In this new church, originally known as the African Mennonite Mission and then renamed Diamond Street Mennonite Church after its move to West Diamond Street in 1942, members were expected to conform to the dress expectations of their white Mennonite counterparts even though they could not participate in services with these fellow believers. According to one scholar, many African American Mennonite women embraced plain dress as a way of showing their equality with white Mennonites and challenging racial hierarchies within the church; others balked at these practices, resulting in tensions with missionaries and other church leaders.

Even as Philadelphia Mennonites faced these and other particular tensions, a century and a half of religious, economic, and social change propelled Mennonites across North America to alter, adapt, or even discard some elements of their religious beliefs and practices. Despite regional and cultural variations and differences, especially between urban and rural communities, three major transitions occurred during the middle decades of the twentieth century. During World War II, many Mennonites transformed the church’s commitment to nonviolence from a passive refusal to join the military to an active pursuit of peace and justice, often embodied in war relief, humanitarian aid, and economic development efforts. Around the same time, many leaders began to view plain dress, nonparticipation in politics, and other practices as ethnic conventions, rather than biblical or theological mandates, and subsequently ceased to require them of new members. And during the Civil Rights movement and the Vietnam War in the 1950s and 1960s, some Mennonites stepped outside the ethnic enclave and translated their convictions about peace and justice into overt activism in support of the antiwar and Black-freedom causes.

Among Philadelphia Mennonites, these broader changes paralleled an explosive period of church growth. By the 1950s, different Mennonite groups had established a mere five separate congregations in the city, in addition to the many rural congregations scattered throughout Bucks and Montgomery Counties; one congregation in Greenwood, Sussex County, Delaware; and one congregation in Oxford, Warren County, New Jersey. But by 2000, Mennonites had seventeen congregations in the city proper, with several more in the city suburbs and dozens in the surrounding counties; ten congregations in Delaware; and sixteen congregations in New Jersey.

The post-1950 growth signaled a new era of Mennonite presence in Philadelphia. While some churches remained predominantly white, most of the new congregations were racially and ethnically diverse. Members of these new churches embraced a self-conscious Mennonite identity, but did so without European ancestry. Many Mennonites’ transition away from ethnic separatism as well as their newfound activism on behalf of peace and justice issues made them more sensitive to the needs and attitudes of their diverse, urban neighbors. In the 1960s and 1970s, numerous African Americans and Latino/as joined established Mennonite congregations or started new ones. In the 1970s and 1980s, waves of immigration from Global South nations such as India, Vietnam, China, Ethiopia, and others, led to the establishment of several new Mennonite churches in the city. By the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, many Mennonites in Philadelphia worshiped in a language other than English—a fact that linked them to their German- and Dutch-speaking spiritual ancestors who arrived in Philadelphia some three hundred years earlier.

Devin C. Manzullo-Thomas is lecturer in the humanities and director of the E. Morris and Leone Sider Institute for Anabaptist, Pietist, and Wesleyan Studies at Messiah College and a Ph.D. candidate in American history at Temple University in Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Biography of William Rittenhouse (German Historical Institute)

- Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

- Quaker Protest Against Slavery in the New World, 1688 (Bryn Mawr College Special Collections)

- Religious Membership Report, Philadelphia County, 2010 (Association of Religion Data Archives)

- Rittenhouse Homestead and Bake House (Rittenhousetown.org)