Monument to Six Million Jewish Martyrs

Essay

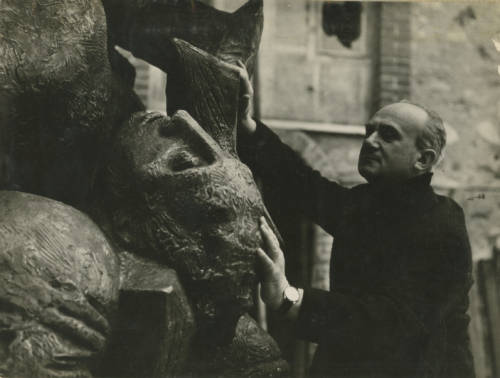

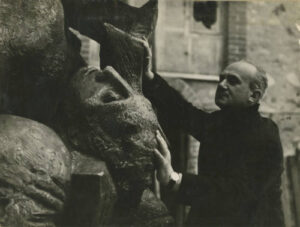

Monument to Six Million Jewish Martyrs, at Sixteenth and Arch Streets at the start of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, is an 18-foot, 5-ton bronze sculpture by Nathan Rapoport (1911-1987). Dedicated on April 26, 1964, it was the first public monument memorializing victims of the Holocaust in North America and the only such monument in Philadelphia. In 2018, the surrounding triangular site, previously populated by several trees, was reimagined as the Horwitz-Wasserman Holocaust Memorial Plaza. Although the plaza formally marked the space around Monument to Six Million Jewish Martyrs as a site of remembrance, reflection, and education, the sculpture has been an educationally and culturally significant landmark since its installation.

The sculpture, cast in Pietrasanta, Italy, rests on a granite base, which is inscribed on all four sides. The side facing the Benjamin Franklin Parkway announces the sculpture’s presentation to the city by the Association of Jewish New Americans and the Federation of Jewish Agencies of Greater Philadelphia. Members of the two organizations, composed of Holocaust survivors and local Jewish leaders, jointly commissioned Rapoport to create the monument in 1962. Interest in commissioning the monument built on community practices of memorialization, while responding to general public silence surrounding the Holocaust and local anti-Semitic activity. The commission required symbolism depicting resistance during the Holocaust, the destruction of Judaism, and life after the Holocaust.

The side facing the Memorial Plaza lists Nazi concentration camps and death camps beneath the directive “REMEMBER” in English and Hebrew. The side facing Arch Street reads, in Yiddish and Hebrew: “In memory of the six million Jewish Holy Souls, who persevered through the Nazis 1933-1945. Remember our brothers, the Holiness of HaShem, who were murdered at the hands of the Nazis.” The side facing Sixteenth Street declares, in English: “Now and forever enshrined in memory are the six million Jewish martyrs who perished in concentration camps, ghettos, and gas chambers. In their deepest agony they clung to the image of humanity, and their acts of resistance in the forests and ghettos redeemed the honor of man. Their suffering and heroism are forever branded upon our conscience, and shall be remembered from generation to generation.”

Suffering and Heroism

Suffering and heroism are vividly depicted in the sculpture through figurative illustrations of anguish and symbols of resistance. Just above the base, a woman rests in apparent pain, her head tilting backwards. Directly above her, a child reaches outward, mouth agape and eyes wide, an expression suggesting fear. Together, these figures evoke deep suffering. Above them, additional figures illustrate the endurance of faith: a praying man stretches his hands upward and a pair of hands holds the Torah scrolls. Flames encircle the sculpture, which may signify the spiritual redemption of the Burning Bush. Some scholars identify angular forms near the bottom of the sculpture as barbed wire, while others assert that these sharp forms are additional flames. Near the top of the sculpture, hands clutch daggers, symbolizing heroic resistance, among the flames of a menorah.

Entwined suffering and heroism is a significant theme in Rapoport’s major sculptural works, such as Monument to the Ghetto Heroes (1948), memorializing the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (1943) in Warsaw, Poland. Born and raised by working-class Jewish parents in Warsaw, Rapoport decided at age fourteen that he wanted to be a painter. After learning that painting classes at the municipal school of art were full, he enrolled in a sculpture course. As a teenager, he worked in an architectural workshop and alongside a sculptor restoring a palace. He earned enough money to enter the Academy of Art, where he gained recognition for works such as Tennis Player (1936) and received scholarships to travel to Italy and France.

In 1939, when Germany invaded Poland, Rapoport left Warsaw in search of the reorganized Polish army. He ultimately joined a collective of Jewish artists in Soviet Union-controlled Bialystock, Poland. There, he gained the attention of Art Commission officials and was given studio space in Minsk, Belarus. Rapoport spent several tumultuous years in the Soviet Union, creating sculptures, working in a labor battalion, and then being pulled from the battalion by a state official affiliated with the Art Commission, who provided studio and living space in Novosibirsk, Russia. In the winter of 1945-46, when the war ended, he returned to Warsaw before moving to Paris, France, in 1948, then living and working in Ramat Gan, Israel, and New York, New York, in the 1950s. Between the completion of Monument to the Ghetto Heroes (1948) and Monument to Six Million Jewish Martyrs (1964), Rapoport created Monument to Mordechai Anielewicz (1951) at Kibbutz Yad Mordechai, Israel. He later memorialized suffering and heroism throughout the Holocaust in the surrounding region: Korczak’s Last Walk (1980) in New York, New York, and Liberation (1985) in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Central Location

Monument to Six Million Jewish Martyrs was originally slated for installation at Gratz College’s North Philadelphia campus. However, the Association of Jewish New Americans and the Federation of Jewish Agencies of Greater Philadelphia pushed for its central location to ensure that the sculpture would reach a broad audience and raise public awareness of the horrors of the Holocaust. In 1966, the two organizations created the Memorial Committee for the Six Million Martyrs within the Jewish Community Relations Council to address physical conditions around the sculpture and expand its cultural and pedagogical influence. The committee worked to promote interfaith dialogue, encourage visits to the sculpture, and distribute educational materials to public schools. It also organized yearly services memorializing Holocaust victims and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Beyond annual memorial services, the sculpture has also been the site of vigils raising awareness of political struggles, such as the oppression of Jewish communities in the Soviet Union and Syria (1972).

In 2006, the Philadelphia Holocaust Remembrance Foundation renewed efforts to preserve Monument to Six Million Jewish Martyrs, increase public access to the sculpture, and expand educational programming. The Horwitz-Wasserman Holocaust Memorial Plaza, dedicated on October 22, 2018, was the dynamic culmination of the foundation’s ongoing work. The plaza features interpretive signs, an eternal flame video display, a tree grove representing resistance and shelter from the Nazi regime, a Theresienstadt tree symbolizing hope, train tracks from the Treblinka death camp, and the option to download a mobile application for a guided tour. As a dedicated center of remembrance and learning, the plaza situates Monument to Six Million Jewish Martyrs as the poignant anchor of an expanded memorial landscape.

Kristin Hankins is a Lecturer in American Studies at Yale University. She studies urban history and geography, public space, and visual culture.

Copyright, 2022, Rutgers University.