Penn Center

By Matthew Smalarz | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

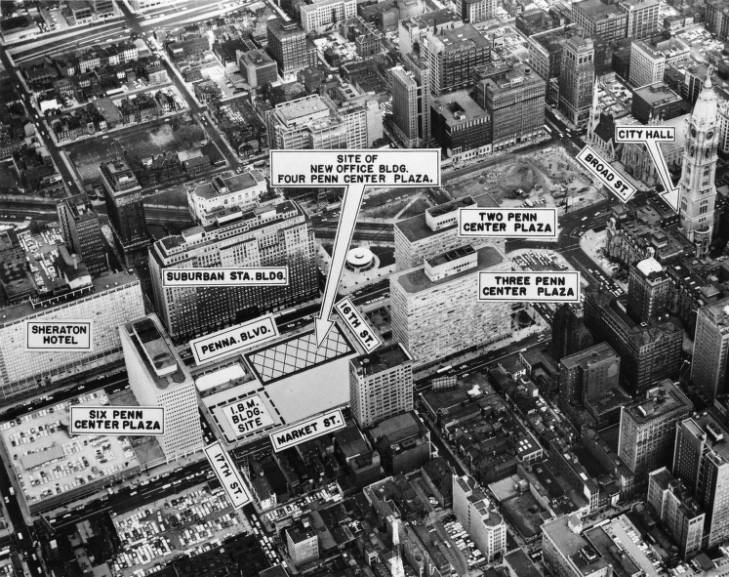

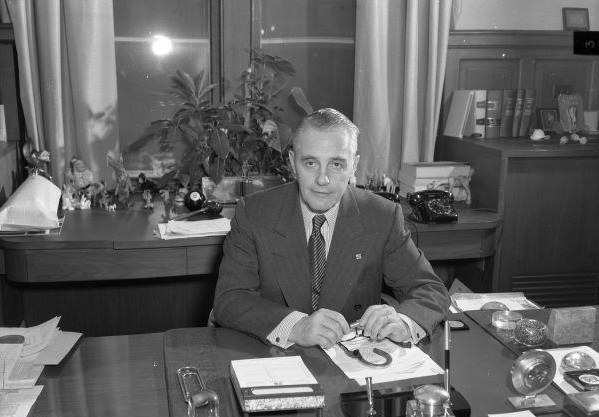

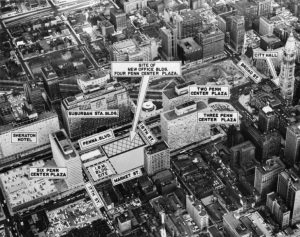

Deemed one of the boldest planning projects undertaken by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission during the mid-twentieth century, Penn Center replaced the Pennsylvania Railroad’s infamous “Chinese Wall” viaduct and Broad Street Station in Center City with modern civic spaces and commercial structures. The complex, which grew to comprise thirteen buildings stretching from Market Street and John F. Kennedy Boulevard, embodied the planning strengths and limitations of its visionary originator, Edmund Bacon (1910-2005). The final rendering of Penn Center, far from its intended original design, nonetheless signaled the growing influence of city planning under Bacon’s stewardship during the 1950s.

Penn Center originated from business and civic reformers’ collective efforts to rehabilitate both the physical and political state of the city after years of Republican machine rule. Through the formation of the City Policy Committee starting in the late 1930s, they sought to modernize the city’s physical state and in 1942 also reconfigured the City Planning Commission, which had been established in 1929 with the consent of the Philadelphia City Council. To further extend the reach of their work, they forged the Citizens’ Council on City Planning in 1943 to advocate for and supervise the actions of the commission. As the culmination of their collective activities, the Better Philadelphia Exhibition in 1947 at Gimbel Bros. department store evoked through the vision of architects Oscar Stonorov (1905-70) and Louis Kahn (1901-74) a transformation of the heart of the city through the creation of Independence Mall, the rehabilitation of what came to be called Society Hill, and, most notably, Penn Center as the centerpiece to the city’s central commercial district.

One of the principal obstacles to realizing the Penn Center project was the so-called “Chinese Wall,” constructed by the Pennsylvania Railroad on a six-block stretch along Market Street, which physically divided and impeded the physical redevelopment of downtown Philadelphia.

Stonorov and Kahn, who had been selected by the planning commission to create a redevelopment plan for the Chinese Wall site, proposed constructing three new commercial structures and a submerged, pedestrian walkway that would mimic Rockefeller Center in New York City. Seeking to maximize its financial investment in the site, the Pennsylvania Railroad fought the plan, and it was up to Bacon, on assuming the position of planning director in 1949, to resolve the issue.

The Early Proposals

Bacon’s first instinct was to collaborate with Kahn, who envisioned eleven symmetrical structures that would span from the Chinese Wall to the Schuylkill River, with a pedestrian walkway traversing them from beneath—an expansion of his earlier design concept from the Better Philadelphia Exhibition. Bacon, however, eventually deemed Kahn’s vision impractical. He soon turned to Vincent Kling (1916-2013), an innovative, young architect known for his professional and architectural connections to the railroad, to design a model that would encompass three office structures on the eastern half of the Chinese Wall, a submerged concourse dotted with stores, and nearby access to the Suburban Station concourse. Encouraged by interest expressed by James Symes (1897-1976), the presumed heir to the Pennsylvania Railroad, Bacon used a luncheon for members of the Citizens’ Council on City Planning on February 21, 1952, to announce that the Public Utilities Commission had agreed to allow the railroad to dismantle the Chinese Wall and Broad Street Station, a seventy-one-year-old railroad depot located at Broad and Market Streets, to make way for the project. Although Symes hinted that the site’s future redevelopment had yet to be completely determined, Bacon officially designated the project Penn Center and declared that “these plans represent a conception of a way of rebuilding . . . the city core expressive of the dignity of Philadelphia as the center of a growing metropolitan region.”

Bacon and newly elected Democratic Mayor Joseph Clark (1901-90), an outspoken municipal reformer who highlighted the centrality of Penn Center to the city’s comprehensive planning agenda, soon experienced setbacks. At the insistence of its president, Martin Clement (1881-1966), the railroad sought to make a quick profit by selling the site piecemeal rather than developing it as one continuous project. In addition, a number of civic organizations objected to Bacon’s suggestion of making way for the project by dismantling City Hall, with the exception of its tower. Bacon’s Penn Center Redevelopment Area Plan, which reached from Vine Street to Market Street, released in August 1952, answered critics by arguing that while the Chinese Wall site was privately owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad, the city was within its purview to redevelop adjoining properties in the immediate vicinity. Although the proposal did not include City Hall, it nevertheless heeded civic fears by calling for a study to determine the merits and liabilities of refurbishing or razing it. To advance the city’s unified vision for the site among the railroad’s leadership, which entertained offers from numerous developers, the plan called for a pedestrian walkway, additional surface transit lines, and a submerged expressway at Vine Street as well as a height restriction of 340 feet on newly erected structures to ensure that City Hall remained the tallest building in the city if it was retained.

For Bacon, the planning document proved insufficient to achieve his goals. The Pennsylvania Railroad demolished the Chinese Wall in May 1953, but instead of cooperating with the planning commission it leased two blocks of property at Fifteenth and Market Streets on the site to Uris Brothers, a real estate development firm from New York City, which proposed designing and building a drab, twenty-story structure designated “Three Penn Center,” further eroding Bacon’s goal of developing the land as one continuous project. Although Bacon had repeatedly sought to compel the Pennsylvania Railroad to incorporate the aesthetic and civic dimensions of the city’s Penn Center Plan, the railroad ultimately aligned with private developers to design a project intended to yield profitable returns.

First Up: Three Penn Center

As construction on the first Penn Center structure Three Penn Center commenced in late November 1953, Mayor Clark persuaded representatives from the railroad to construct the submerged pedestrian walkway, one of the plan’s critical features. But Bacon could not persuade the developers of the site to embrace most of his ideas for Penn Center, especially the inclusion of a continually open concourse. The final product and its four surrounding offshoots, which spanned from Market Street to JFK Boulevard and consisted of glass and concrete building materials, was widely condemned by architectural critics who deemed it “pretty miserable” and “an uninspired compromise with real estate interests” by its near completion in the late 1950s.

Despite Bacon’s dismay with the aesthetic features of Penn Center, he did not view the project as an abject failure, for he regarded it as an integral part of the broader redevelopment of downtown Philadelphia. He partnered with Dean Holmes Perkins (1904-2004), a city planner and dean of the Graduate School of Fine Arts at the University of Pennsylvania, who was installed by Mayor Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974) as chairman of the City Planning Commission, to acquire and mold the properties surrounding Penn Center into visibly appealing public spaces. The most notable of these public spaces, Dilworth Plaza (later Dilworth Park), occupied part of Penn Square, one of William Penn’s five original public squares for the city and the site of City Hall. He also collaborated with Vincent Kling to design a public plaza, later known as John F. Kennedy Plaza and LOVE Park, at the eastern end of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. To maintain the historical connection between the physical centrality of City Hall and William Penn’s original plan for the center of the city, he also devised an “unwritten gentleman’s agreement” compelling builders to only erect structures that would not eclipse William Penn’s statue atop City Hall, which stood at 548 feet as the highest structure in Philadelphia, an idea that had first appeared in the 1952 Penn Center Redevelopment Plan, which would be completed by the early 1960s.

Despite architectural criticism, Penn Center advanced Bacon’s broader agenda to modernize the physical appearance of downtown and signaled the emerging impact of city planning recommendations on the decision-making processes of private corporations in advocating for the needs of the city.

Matthew Smalarz teaches history at Manor College in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, where he serves as Chair of Social Sciences as well as History and Social Sciences Coordinator.

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University