Pietism

Essay

Pietism was the source for much of the early religious vitality and diversity in Philadelphia. Between 1683 and 1800 thousands of Pietists crossed the Atlantic Ocean looking for a place where they could follow their conscience in religious matters. Pennsylvania became an attractive destination thanks to the goodwill fostered by William Penn’s missionary journey to Germany in 1677. Although Penn’s goal was to further the cause of the Quaker faith in German territories, the friendships he developed among Pietists yielded dividends for his new colony. Pietist beliefs were commonly found among German settlers who embraced the freedom to practice their religion according to their scruples. Pietism also spread throughout the region circulating among laypeople and clergy. Many American Protestant churches, especially evangelical churches, were influenced by the Pietist commitment to a heartfelt conversion experience that emphasized a dynamic and activist personal faith. Into the twenty-first century elements of Pietism remained in many of the beliefs and practices of churches throughout the Philadelphia region.

Originating from German-speaking Europe, Pietism was an international network of early modern laypeople and clergy who hoped to revitalize Christian devotion in the lives of ordinary people. Although the sources for Pietism were many and often disputed, the roots of the movement are found in the work of Johann Arndt, Martin Luther, English Puritans and other Calvinists, and even the mystical elements of the medieval Roman Catholic Church. Pietism emanated from the thought and work of two Germans, Philip Jacob Spener (1635-1705) and August Hermann Francke (1663-1727), who hoped to reform Protestant churches in late seventeenth-century Prussia. Spener, a preacher and theologian, wrote the principal text of Pietism, Pia Desideria (1675), while Francke, a professor at the University of Halle, established the chief institutions of Pietism with his massive orphan houses, schools, and charitable works in Halle, known as the Halle Foundations. Francke’s labors influenced Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf (1700-60), leader of the Moravians. Francke and the Moravians subsequently shaped the thought and practice of two Church of England clergymen, George Whitefield (1714-70) and John Wesley (1703-91), the founder of the Methodists, each of whom played an important role in the Great Awakening. The breadth of Pietist influence was not limited to these few individuals but included diverse practitioners of radical Pietism who brought an entrepreneurial ethos to the movement that empowered women and men through a dynamic and activist Christian faith.

Arising in the wake of the devastating social and cultural effects of the Thirty Years’ War in German lands, Pietism was a response to the Lutheran Church’s emphasis on doctrine and church governance that did little to connect theological ideas with everyday Christian living. The early Pietists responded to this moral and religious morass in the second half of the seventeenth century by encouraging an experiential religion that focused on an individual coming to faith in Christ through a heart-felt change, emphasizing the importance of the Bible for Christian belief, living out their faith through pious practices, and seeking to socially and morally reform the world. Pietists also believed that the Second Coming of Christ would be preceded by revivals that would restore the true church and lead to the conversion of peoples around the world. This focus on the end times, or eschatology, was rooted in fears about religious wars but also pointed to the hope for the eventual victory of Christ and the church over a fallen world. More radical Pietists engaged in a wide-range of practices from prophetic utterances to ascetic and communal living experiments. Radicals were also often advocates for equality among the sexes and races, which further alienated Pietists from the mainstream society. In the context of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Pietists’ religious and political opponents sharply rebuked them as social, religious, and political subversives and shunned their experience-based and emotional form of Christianity. Despite being embattled, Pietists continued to attract followers. Their emphasis on a reorientation of one’s personal life after salvation encouraged personal transformation through small group Bible study, ethical living, social activism, and supporting Christian missions and evangelism.

Pietists come to Pennsylvania

Pietism flourished in several German cities, including Frankfort am Main, Halle, Württemberg, Heidelberg, and Herrnhut, and immigrants from those areas directly influenced religion in and around Philadelphia. The persecution of Pietists by German state authorities encouraged their migration to North America. By 1682, Pietists in Frankfurt organized the Frankfurt Land Company to sell land purchased from William Penn (1644-1718) to German Pietists. Francis Daniel Pastorius (1651-c.1720), a Pietist business agent for the Frankfurt Land Company who later became a Quaker, helped establish Germantown in 1683. Promotional tracts written for Germans Pietists highlighted Pennsylvania as a land free from the immorality and decadence that religious separatists believed troubled Europe. After the invasion of German territories by the forces of the French king Louis XIV, many Pietists and religious dissenters escaped to Pennsylvania seeking peace and the freedom to follow their conscience in matters of faith.

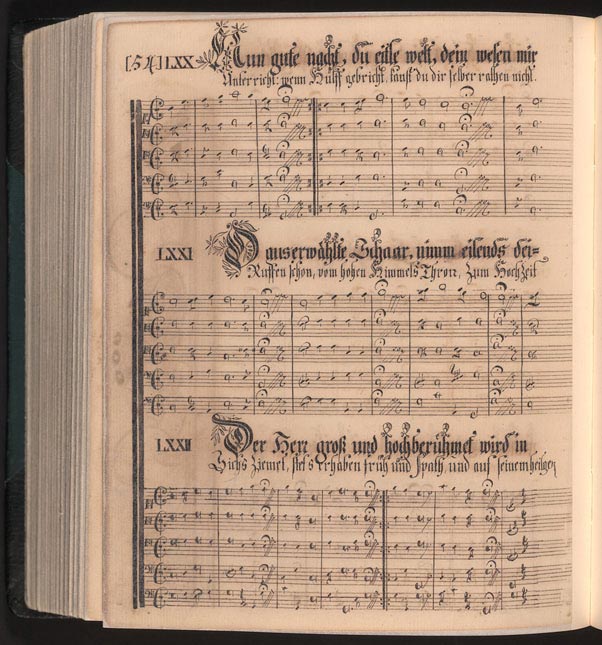

Some of the radical Pietists who came to Pennsylvania held beliefs that reflected the transition from the magically-infused early modern world to the scientific rationality of the modern world. One such example was Johannes Kelpius (1673-1708), who arrived in Philadelphia around 1694 and was a member of a radical Pietist sect known as the “Chapter of Perfection” established by Johann Jakob Zimmermann (1642-93). Using numerology, prophecy, and a close reading of world events, Zimmermann believed that Jesus Christ would soon return. In anticipation of Christ’s arrival, he planned to travel with a group of mystically-minded monks to Pennsylvania to prepare for the momentous event. Zimmermann, however, died before he could see his vision fulfilled, and Kelpius took the helm of leadership and secured passage for the men to Philadelphia. Kelpius’s hermit community, often referred to as the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness based on Revelation 12:6, settled in the wilderness along Wissahickon Creek where they built a small tabernacle and waited for the Second Coming of Christ. Another radical Pietist who followed in Kelpius’s footsteps was Conrad Beissel (1691-1768). In 1732, he founded the community at Ephrata, also known as the “Camp of Solitaries.” By 1755, the community had reached the apex of membership with some three hundred to four hundred residents in separate houses for men, women, and families. Ephrata was noted for its distinctive piety, art, music, dress, emphasis on celibacy, and communal living. Eventually, the community dwindled in size and reorganized as the German Seventh-Day Baptist Church in the early nineteenth century.

Another group of radical German Pietists in colonial Pennsylvania who were influential among early German immigrants were the Unitas Fratrum, more commonly known as the Moravians. They, along with other religious refugees, sought protection from Emperor Charles VI on the lands of Count Zinzendorf in Germany. Zinzendorf, a former student of Francke in Halle, gave the Moravians a Pietist vision for global missionary work and sent groups of Moravians to North America. The first Moravians migrated to Germantown, but later groups made their mark on Philadelphia and the surrounding region. They established settlements at Lititz, Nazareth, Emmaus, and Bethlehem, where they made a significant contribution to female education in the colony. They also brought their love of music with them to Pennsylvania and wrote sacred music, sang hymns and chants, and played in orchestras that brought them acclaim. Moravians were noted also for their evangelism, particularly among Native Americans and African slaves.

Pietists influence the development of American Lutheranism

By 1740, Pennsylvania had twenty-seven Lutheran churches, but due to a severe shortage of clergymen, only a few pastors could be found to lead them. To partially fill this void, German Pietist leader Gotthilf August Francke (1696-1769), son of August Hermann Francke, encouraged Henry Melchior Mühlenberg (1711-87) to travel to Philadelphia to provide leadership to Lutheran congregations. Arriving in 1742, Mühlenberg recognized the gravity of the situation and gave his complete devotion to his pastoral and ecclesiastical duties in Philadelphia and the surrounding area. He recorded his experiences in Hallesche Nachrichten, one of the most detailed accounts of everyday life in Pennsylvania from the colonial period. Mühlenberg organized the first Lutheran church body in the colonies, the Evangelical Lutheran Ministerium of Pennsylvania, that oversaw the steady growth of Lutheran churches in the region. Pietism also influenced his belief in the power of education to reform society. He strove to found schools as an avenue for encouraging individual piety and civic mindedness. Due to his industrious educational and ecclesiastical efforts he is considered the “Father of American Lutheranism.”

Pietism was a late-seventeenth and eighteenth-century movement that was vitally important for the development of Protestant Christianity in Philadelphia and the surrounding region. Even though Pietism did not remain an essential aspect of American Lutheranism beyond the early nineteenth century, the influence of Pietist churches and the American revivalist tradition perpetuated traces of Pietism among adherents of Methodist and Holiness churches throughout the nineteenth century. During the twentieth century, Pentecostals and Charismatics, heirs of the Holiness movement, embodied a new incarnation of Pietist radicalism that harked back to the religious impulses found in early colonial Philadelphia.

Darin D. Lenz, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of History at Fresno Pacific University.

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History