Political Parties (Origins, 1790s)

Essay

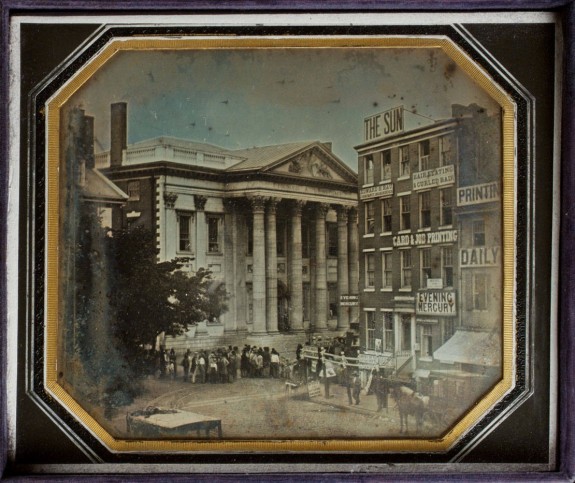

Philadelphia, long considered the “cradle of liberty” in America, was also the “cradle of political parties” that emerged in American politics during the 1790s, when the city was also the fledgling nation’s capital. A decade that began with the unanimously-chosen George Washington (1732-99) as the first President of the United States ended with partisan rancor, as the economic policies of Alexander Hamilton (1757-1804), tensions in America’s relationship with France, and the controversial Jay Treaty with England divided Americans into two distinct political parties which had little, if anything, in common. Philadelphia was the epicenter of this political earthquake.

However, partisan rancor in Philadelphia was not caused by the creation and presence of the federal government. Political factions and rivalries that had existed at the local level for many years were exacerbated by the fighting that emerged at the national level. Federalists who fostered an image of rule by the elites took the reins of government in a city and commonwealth where the disaffected “have-nots” had waged political war with the “haves” since the 1750s and 1760s, when Benjamin Franklin allied with many Quakers against the proprietorship of the Penn family–a family who (they believed) exploited the province for revenue.

On the national level, the signing of the U.S. Constitution in Philadelphia in 1787 and the subsequent ratification battles in the states created two distinct factions–“Federalists” who supported the document and “Anti-Federalists” who opposed it. The First Congress, which initially convened in New York in 1789 before moving to Philadelphia in 1790, consisted of men from both factions and reached agreement on a Bill of Rights and the establishment of Cabinet departments. But the proposals set forth by Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton created schisms that only widened during Washington’s administration. One such proposal involved the assumption of state war debts by the federal government. This plan angered those from states who had already paid off a large portion of their debts. Virginia Congressman James Madison (1751-1836), who had written many of the “Federalist Papers” along with Hamilton to promote the ratification of the Constitution, was one of those who sternly opposed Hamilton’s measures. Pennsylvania denounced the “funding scheme” as well, especially when speculators who became aware of the plan galloped across the countryside and bought up debt certificates from unsuspecting Pennsylvania veterans.

Early Divisions

When Hamilton later proposed the creation of a national bank, Madison was joined in his battle by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), who was alarmed at the growth and encroachment of the new central government and the bank’s questionable constitutionality. “A distinctive Anti-Federalist agenda emerged,” wrote Saul Cornell in The Other Founders. “The goal of Anti-Federalists was to limit the powers of the new government and bolster the states so that they would continue to be in a position to protect the liberty of their citizens.” By 1792, those opposed to Hamilton’s programs had coalesced into the Democratic-Republican Party (also styled as “Jeffersonians”). The elections in that year saw many gains by the nascent party and a majority in the U.S. House of Representatives.

The fissure between Jefferson’s party and Hamilton’s was caused by more than banks and debts. The Washington administration’s foreign policy made the gap even wider, as Hamilton’s Federalists favored closer ties with the British while the Jeffersonians favored France and the French Revolution. When war between the two European superpowers began in 1793, the Jeffersonians advocated honoring the alliance with France that was made during the American Revolution. Washington, hoping to avoid a war that the country could ill afford, sided with Hamilton and implemented a policy of neutrality, which many Jeffersonians interpreted as favoring Britain. Republicans had also criticized Washington and Vice President John Adams (1735-1826) of having monarchical tendencies, so the link to England was easily made.

During this time in 1793, Democratic Societies began to form across the country. One of the most prominent of these groups was the Pennsylvania Democratic Society, founded in Philadelphia by such prominent citizens as Alexander Dallas (1759-1817), who later served in James Madison’s cabinet. The societies extolled the virtues of the French Revolution and were inspired by Citizen Edmond Genêt, an ambassador from the new French republic to the United States.

Domestic issues also fostered growth among the societies. The Pennsylvania Democratic Society in Philadelphia vehemently opposed Hamilton’s excise tax on whiskey in 1794, which impacted many farmers in western Pennsylvania, and sought to elect officials who would repeal the excise law.

Whiskey Rebellion, French Revolution

Three events soon damaged the credibility of the societies. The French Revolution became more violent, culminating in the beheading of King Louis XVI. Citizen Genêt alienated President Washington by belligerently outfitting American privateers to engage in combat with British ships. And farmers in western Pennsylvania resorted to violence to oppose the excise tax (referred to as the “Whiskey Rebellion”). When Washington denounced the societies as disruptive and unrepublican, they experienced a rapid decline. Yet they served as a framework for the opposition party that emerged by the end of the decade.

An organized opposition party was not new to Pennsylvania. A quasi-party system had been developed in the aftermath of the ratification of its 1776 State Constitution. While the constitution fostered greater democracy by granting voting rights to all men regardless of property ownership, it was inadequate due to the lack of effective checks on the legislature, which soon overreached in its authority to confiscate property and overrule the judiciary. This last element was in direct contrast to the democratic spirit which prevailed in Pennsylvania when the document was drafted, and two parties – a “Constitutionalist” formation and a “Republican” faction which opposed the constitution – emerged. In 1790, Pennsylvanians adopted a new constitution that provided for greater parity among the branches, along with a bicameral legislature and a governor with veto power.

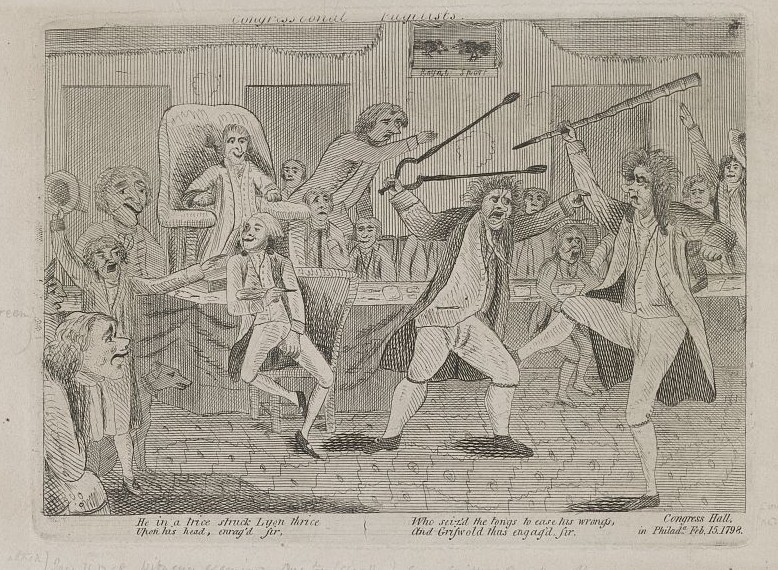

Nationally, the increasing partisanship of the 1790s was mirrored in the press, as Federalists and Republicans waged political war – which often included personal invective – in the pages of the country’s newspapers. In Philadelphia, the nation’s capital, Hamilton and Jefferson not only waged war but hired editors to create and manage partisan newspapers. John Fenno (1751-98) did the Federalists’ bidding in the Gazette of the United States, which originated in New York in 1789 and moved with the government to Philadelphia one year later. The Jeffersonians countered with the National Gazette of Philip Freneau (1752-1832) and the Aurora, which was edited by Benjamin Franklin’s grandson, Benjamin Franklin Bache (1769-98).

The Jay Treaty, signed between the United States and Britain in 1794 and ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1795, further widened the gap between the parties. While the treaty prevented war with Britain, Jeffersonians severely criticized it as a capitulation to England. The treaty did not address certain grievances, particularly the British practice of seizing American ships and the impressment of American seamen. But as a result of the treaty, along with the seeds planted by the Democratic Societies shortly beforehand, Jeffersonian Republicans observed major gains in Pennsylvania in 1796 due primarily to the aftermath of the Jay Treaty, and the Republican movement had, by this time, crystallized into a genuine opposition party.

Pennsylvania’s political evolution in the 1790s was a microcosm of the nation, as opposition to the Federalists steadily grew throughout the decade. The “have-nots” on the Western frontier and among Philadelphia’s urban poor were disillusioned with Hamiltonian policies that foreclosed their farms, taxed their whiskey, and favored the British monarchy over the French republic. By the middle of the decade, moderate Jeffersonians led by Thomas McKean (1734-1817), a signer of the Declaration of Independence and former Federalist, had taken control of the reins of Pennsylvania’s government.

Brian Hendricks is a Ph.D. candidate in early American history at Southern Illinois University. His research focuses on the election of 1796 and the growth of political parties in New York and Pennsylvania.

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History