Public Education (The School District of Philadelphia)

By William W. Cutler III | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

In 1837 the Philadelphia Board of Education—then known as the Board of Controllers—embraced “universal education” and opened the city’s publicly supported and publicly controlled schools to all school-age children, free of tuition. The board proudly proclaimed: “the stigma of poverty, once the only title of admission to our public schools, has . . . been erased from our statute book, and the schools of this city and county are now open to every child.” By the beginning of the twenty-first century, however, many Philadelphia parents had opted for suburban schools, charter schools, or home-schooling, and the School District of Philadelphia had become in many ways what it had originally been—a system for poor and disadvantaged children.

Publicly funded and publicly controlled education in Philadelphia originated in 1818, when alarming changes in the commonwealth’s largest city prompted the Pennsylvania General Assembly to establish the “First School District of Pennsylvania.” Poverty and crime were spiraling out of control as the city’s size increased and its economy expanded. No longer intimate and communal, Philadelphia was becoming what historian Sam Bass Warner once called a “private city.” Turning to the free market in 1802, the legislature provided for the city’s poor children to be taught in private schools at public expense. When this approach to the dual problems of diversity and disorder proved to be inadequate, it authorized the creation of a pauper school system and the election of a Board Controllers to organize and oversee it.

The board’s first president, Quaker reformer Roberts Vaux (1786-1836), soon decided that something more was needed, and in 1827 he formed the Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of Public Schools, by which he meant schools that would be tuition free and open to all children. His vision became a reality through the common school laws of 1834 and 1835 and the Consolidation Act of 1836, which opened Philadelphia’s public schools to all school-age children. With this step, the city joined the common school movement—most often associated with Horace Mann (1796-1859)—that was spreading beyond New England to institutionalize and standardize the way most children were educated. In Philadelphia, these public schools grew quickly, so quickly that they enrolled 17,000 within two years. To manage such numbers, the controllers divided students into three ability groups. In October 1838 they also opened Central High School for boys, locating it on Juniper Street below Market, then the western edge of the developed city.

Basic Education Only

In the nineteenth century most Pennsylvanians did not want anything more than a basic education. Moreover, Philadelphia’s economy sustained many workers who had little, if any schooling. Central High School prospered because the middle class perceived its diploma to be a hedge against downward mobility for their sons and perhaps a stepping stone to business or the professions. The Philadelphia Girls Normal School (later renamed the Philadelphia High School for Girls), which opened in February 1848 in a building on Chester Street previously occupied by the district’s Model School, offered the daughters of the middle class an opportunity to acquire an advanced education.

Many alumnae of Girls Normal became teachers. Women were preferred for this occupation because they were supposedly better with children, especially the very young, and, more importantly, because they were willing to work for much less money than men. But most taught for just a few years because they had to resign if they wed. They also were at the mercy of the prevailing political winds. Some even had to pay to obtain or keep their positions. Interchangeable or not, they still had to be replaced when they departed because the demand for their services was great and growing. By 1867 two-thirds of all Philadelphians between six and twelve years of age attended a school operated by the district, whose enrollment in December1870 stood at nearly 89,000. The district expected its teachers to have more than a basic education, but most started while still in their teens, having been schooled for no more than five or six years.

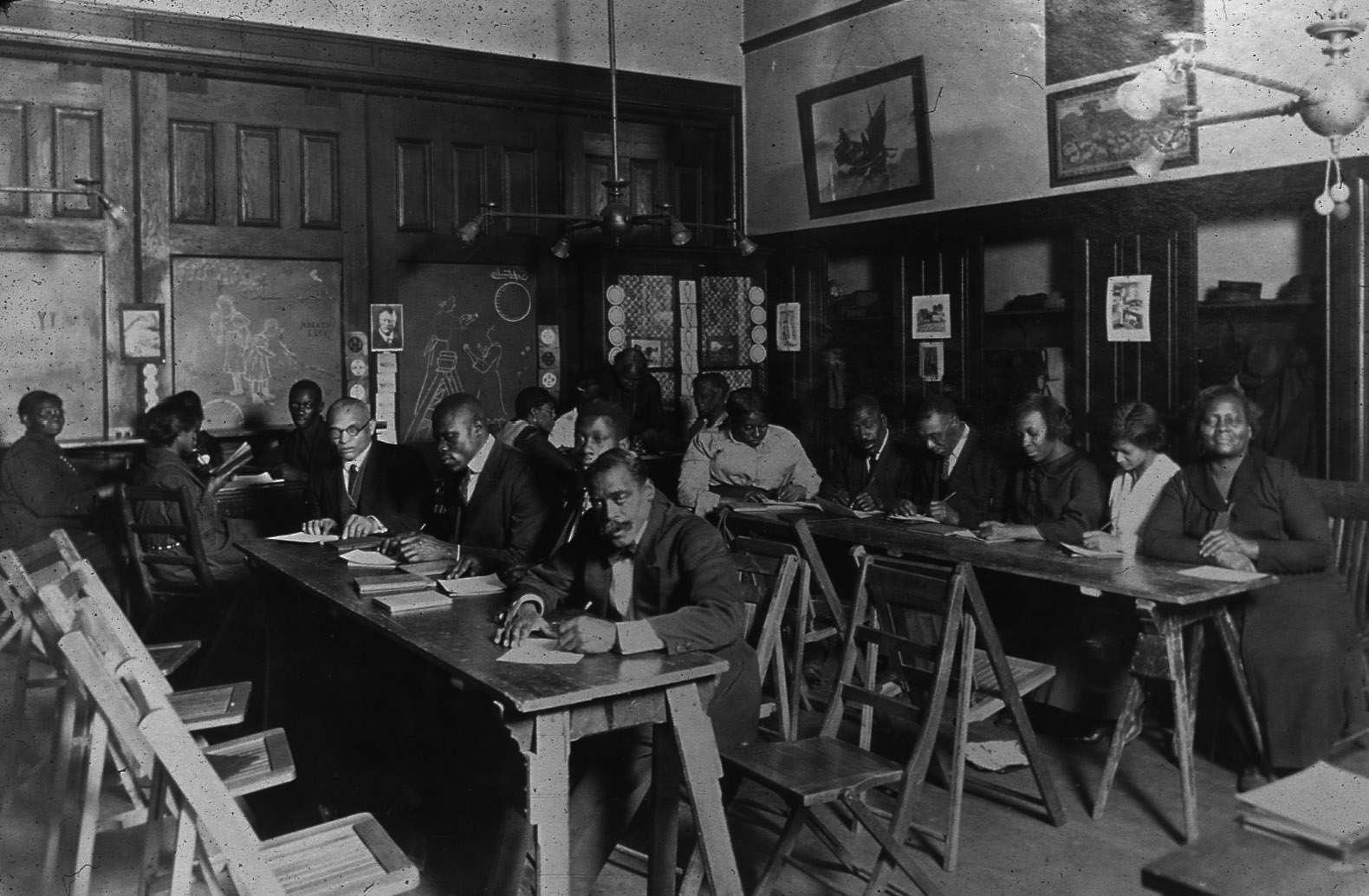

Although Philadelphia public schools were open and free to all for most of the nineteenth century, they were not integrated. Prompted by a wave of black crime and a decline in total enrollment, the controllers opened a primary school for African Americans on Mary Street in 1822. When they opened another on Gaskill Street four years later, it was designated for girls and the other for boys; the practice of sex segregation was widespread then and remained common in the district until the twentieth century. In 1828 both moved into a school at Seventh and Lombard Streets—a location then becoming the heart of Philadelphia’s black community—after the district erected a new building for its white students. Such subtle discrimination became more overt over time, peaking in 1854 when the state legalized the separation of the races in all public schools if twenty or more African American pupils could be educated together. By the time this law was repealed in 1881, segregation had become entrenched in Philadelphia.

Power Largely Decentralized

Power over urban public education was largely decentralized in the mid-nineteenth century. The controllers may have been responsible for collecting and distributing revenue in Philadelphia, but an elected board of directors managed the public schools in each ward in the city. Composed of local business and civic leaders as well as politicians, these boards hired teachers, chose principals, and perhaps most important of all, erected buildings. At first, each ward board chose its own representatives to what became known in 1850 as the Board of Education, but in an attempt to improve the selection process the state legislature gave the right to make such decisions to the judges of the Court of Common Pleas in 1867. For the next forty years civic leaders and professional educators made numerous attempts to weaken the ward boards, even proposing to abolish them altogether. Justified as modern and scientific, these reforms attracted powerful backers, but they struggled to win acceptance. It took revelations of corruption to convince the Pennsylvania legislature that reform was needed. In 1905 it passed a “Reorganization Act” that entrusted a more efficient but less democratic board of education with the power to run the system. Transformed into advisory bodies, the ward boards eventually disappeared.

More than twenty years before the Reorganization Act, centralized control of public education received a boost when the school district hired its first superintendent. Because of opposition by the ward boards, Philadelphia lagged behind other cities in this regard even though its enrollment was rapidly growing, swelling by almost 18 percent in the 1870s. James A. MacAlister (1840-1913) assumed the post in 1883, having been persuaded to leave the same position in Milwaukee. MacAlister came prepared to reform the Philadelphia public schools, as did his successors Edward Brooks (1831-1912) and Martin G. Brumbaugh (1862-1930). MacAlister and Brumbaugh believed the curriculum should include industrial education—a subject that many traditionalists like Brooks believed did not belong in the public school curriculum. While MacAlister was superintendent, the district opened two manual training high schools, Central Manual Training (on the corner of Seventeenth and Wood Streets) and Northeast Manual Training (on Howard Street below Girard Avenue), and the James Forten Elementary Manual Training School for African Americans (on Sixth Street above Lombard).

During the administrations of these three superintendents the district expanded and diversified its curriculum. High schools started teaching modern foreign languages, basic science, and American history. Astronomy was even included in the Central High School course of study, and the school built an observatory when it moved to the northwest corner of Broad and Green Streets in 1900. The district’s evening division offered citizenship and literacy classes for immigrants and African Americans. Physical education also made its appearance in the curriculum. The district assumed responsibility for boys’ sports in 1912, more than thirty years after some students had formed their own interscholastic athletic teams. The introduction of physical education for girls in 1893 led to the formation of girls’ teams that competed on an intramural and, briefly in the 1920s, an interscholastic basis.

Distinguished Superintendents

The district’s first three superintendents were distinguished educators and strong leaders. When he left the district in 1891, MacAlister became the first president of the Drexel Institute of Science, Technology, and Industry (later Drexel University). While Brooks was superintendent, he served on the influential Committee of Fifteen appointed by the National Education Association to reform the elementary school curriculum. Brumbaugh, who helped devise and implement the Reorganization Act, turned his eight years in Philadelphia (1906-1914) into a successful run for the governorship of Pennsylvania. Taken as a whole, the work these superintendents did convinced Philadelphians that their school district needed an eminent man at the helm and centralized, professional leadership.

Although public money had paid for public education in Philadelphia since the days of Roberts Vaux, the school board seldom spent freely because it was never fiscally independent. In 1904 it spent less than its counterparts in thirty-three other American cities. A reform law passed in 1911 gave the board the power to borrow money but not levy taxes, a limitation that was reinforced by the state Supreme Court in 1937. Given these constraints, the School District of Philadelphia usually pinched pennies. Controlled by its business manager, Add B. Anderson (1898-1962), the district balanced its budget for more than thirty years by concentrating on basic instruction and compelling its teachers to accept very low salaries. This strategy may explain why unionization did not take a firm hold among the city’s teachers until Anderson was dead and Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974), once the mayor, took over as school board president. The Philadelphia Federation of Teachers (PFT), which came into existence after the American Federation of Teachers expelled the Philadelphia Teachers Union for radical activity in 1941, struggled to have an impact for more than two decades. When the economic and political climate finally changed in the 1960s, the PFT mounted a successful membership drive and became the exclusive bargaining agent for all the district’s teachers. Empowered in this way, it took full advantage of Act 195, adopted by the state legislature in 1970, that allowed public employees to strike in Pennsylvania.

Six Strikes in 11 Years

Between 1970 and 1981 the PFT went on strike six times—job actions that greatly improved its members’ salaries, benefits, and working conditions but also dramatically increased their employer’s expenses. The school district’s budget more than doubled, from $312 to $711 million, during those years. At the same time, the city’s slow transition from an industrial to a service economy weakened the tax base. A rare combination of slow growth and hyper-inflation further compromised the district’s financial situation. The Board of Education was forced to raise class size and furlough teachers, angering parents as well as PFT leaders. It even resorted to carrying deficits over from one budget year to the next, prompting questions about its fiscal leadership.

Local tax dollars have never been enough to pay for public education in Pennsylvania. Outside money, whether from the common school fund established by the state in 1831 or some other source, has always been needed by local districts. In the mid-1920s the state provided about 14 percent of all the funds spent on public education in Pennsylvania. This figure nearly quadrupled by the mid-1970s before falling back to barely one-third of the total at the end of the twentieth century. Because some school districts have fewer resources than others, the state began making differential appropriations as early as 1921, when a minimum salary law classified school districts by size of enrollment. The smaller the district, the larger the proportion of salary costs that would be offset by the state. This formula disadvantaged the School District of Philadelphia, which had the most students, but even so, its budget gradually became dependent on both state and federal money, especially after the courts and Congress mandated that some students receive more help than others.

Reformers in the 1960s attempted to equalize educational opportunity. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (1965) committed the federal government to providing funding for schools with many low-income children, and the Bilingual Education Act (1968) forced public schools to reconsider how they educated students whose first language was not English. Soon thereafter, the federal courts began to issue rulings in favor of equal access to public education for children with disabilities. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the defendant in a suit filed by the Pennsylvania Association of Retarded Children, faced the charge that its public schools did not treat children with mental disabilities fairly. Settled by mutual consent in 1972, the suit justified equalization subsidies that helped Philadelphia and many suburban school districts cope with the extra costs associated with educating culturally disadvantaged, mentally disabled, and low-income students. These subsidies drove the state’s share of the Philadelphia school budget from 32 to 58 percent between 1967 and 1973 and kept its share of that budget at more than 50 percent until 1992, when a slow decline began that was reversed, if only temporarily, in 2008.

The Racial Divide

In the mid-twentieth century equal access was just as big a problem for African American children as for those with disabilities. Before and after World War II, record numbers of southern blacks migrated to Philadelphia. Confronted by pervasive discrimination, they settled in neighborhoods that soon became almost completely segregated. Not surprisingly, the public schools in those neighborhoods also became segregated. Responding slowly to the Supreme Court’s landmark decision, Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the School District of Philadelphia did not adopt a non-discrimination policy until five years later. In 1963 a committee appointed by the Board of Education recommended that school boundary lines be redrawn and a school building program be developed to promote integration. But lacking the political will to implement such controversial plans, the board soon faced a discrimination suit filed by the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission. It remained unresolved for many years. In 1983 Constance Clayton, the first African American to be named the district’s superintendent, tried to convince the commission to withdraw its suit by preparing and implementing a “modified desegregation plan” that depended heavily upon voluntary compliance. It met with widespread approval, but many white Philadelphians shunned the city’s public schools anyway, especially in blue collar neighborhoods, and by 2010 white children comprised only 20 percent of the district’s student population. These demographic realities convinced the commission in 2004 to substitute the fair distribution of resources within the system for desegregation as the principal condition for a settlement.

When Clayton became the superintendent in 1982 the reputation of the school district had sunk to a very low level. Philadelphia was not alone in this regard; by then public schools in many cities were perceived to be failing. Some reformers proposed a return to public control at the neighborhood level, arguing that parents, not bureaucrats, knew what was best for their children’s education. New York City implemented a limited decentralization plan in 1968, but Philadelphia took a different path in part because of Richardson Dilworth. He favored making the school board smaller and more accountable to the mayor, changes that were adopted by referendum in 1965.

Dilworth’s leadership of the board proved to be no more transformative than that of his predecessors. Mark Shedd (1926-1986), hired by Dilworth to run a school district then enrolling nearly 280,000 children, embraced innovations like the Parkway Program, an experimental high school that gave a few students unprecedented freedom of choice in selecting courses and teachers. He also created a resource center for African American studies and ordered that black history be taught in every high school in the city, but this order fell on deaf ears and remained unfulfilled for nearly forty years. Shedd ran afoul of the city’s ambitious Police Commissioner, Frank L. Rizzo (1920-1991), who considered the superintendent to be a soft-hearted liberal. When Rizzo was elected mayor in 1971, Shedd decided to leave, joining the faculty of his alma mater, the Harvard Graduate School of Education. His successors, Matthew Constanzo and Michael Marcase, were no match for the district’s political and financial problems. After three years on the job Costanzo became the superintendent in Haddonfield, New Jersey; Marcase lasted longer but fell farther, leaving after seven years to teach educational administration at Temple University.

Calm Under Clayton

Clayton brought more than a decade of relative calm to the Philadelphia school district, stabilizing its budget and restoring its image. She mandated a standardized curriculum based upon the idea that all students could learn all subjects and all disciplines. She took a special interest in struggling students. Programs in such fields as business, health, and electrical science were embedded in some of the city’s comprehensive high schools. With the assistance of the Pew Charitable Trusts, “small learning communities” also were created in these high schools.

But Clayton did not solve the problem of equal access or contain the costs of the district’s operation. The superintendents who followed her—David Hornbeck, Paul Vallas, and Arlene Ackerman—stressed improving student achievement, but each burned out within a few years. Hornbeck won few converts when he angrily accused the state legislature of malpractice for under-funding education for low-income African Americans. Vallas may have had no choice when he downsized the district, selling its elegant administration building on Twenty-First Street and expelling violent students, but he alienated many allies, especially African American teachers and principals. Ackerman’s attempts to win them back were so heavy-handed that she lost credibility with the power brokers she needed to remain superintendent.

By the time Vallas arrived in 2001, the Board of Education had ceased to exist, replaced by what came to be known as the School Reform Commission (SRC). Made possible by the Education Empowerment Act (2000), the SRC brought an end to local control of public education. Too many appeals for more money had finally convinced the governor and the legislature to assert state control. The district would be run by a committee of five, three chosen by the governor and two by the mayor. The idea that the city’s public schools should educate every child also faded. In competition with private schools, charter schools, and suburban school districts, enrollment in the School District of Philadelphia dropped by more than 45,000 students in just four years, from about 207,000 in 2006 to about 160,000 in 2010. At the same time, its proportion of low-income students reached more than 70 percent.

The SRC governed the School District of Philadelphia for seventeen years (2001-18). During that time it never enjoyed the full support of the city’s politicians or the district’s parents and teachers. Two of the three superintendents it hired–Paul Vallas (b. 1953) and Arlene Ackerman (1947-2013)–left abruptly and under a cloud. The SRC often offended politicians by running deficits, parents by closing schools, and teachers by laying off employees and canceling its contract with their union. After being elected mayor in 2017, James F. Kenney (b. 1958) called for the return of local control, and in 2017 the SRC voted itself out of existence, effective June 30, 2018. Under a new board of education appointed by the mayor, the School District operated once again under familiar rules.

With unreliable sources of income and students among the neediest, by the second decade of the twenty-first century the School District of Philadelphia resembled the educational system that Roberts Vaux rejected when he first called for reform in the 1820s. That system relied on parental initiative, similar to what the proponents of vouchers advocate to solve the problems of public education in the twenty-first century. Perhaps Vaux would not understand everything about modern education, but he would certainly grasp the meaning of these numbers and this proposal for the school district he created. They belie his vision for a publicly supported, publicly controlled system of schools open to all and free of tuition.

School District of Philadelphia Superintendents, 1883-2022

James MacAlister, 1883-91

Edward Brooks, 1891-1905

Martin G. Brumbaugh, 1906-14

John P. Garber, 1915-21

Edwin C, Broome 1921-38

Louis Nusbaum (acting), 1939

Alexander J. Stoddard, 1939-48

Louis P. Hoyer, 1948-55

Allen H. Wetter, 1955-64

C. Taylor Whittier, 1964-67

Mark R. Shedd, 1967-72

Matthew W. Constanzo, 1972-75

Michael P. Marcase, 1975-82

Constance Clayton, 1982-93

David Hornbeck, 1994-2000

Diedre Farmbry, 2000-2 (chief academic officer)

Paul R. Goldsmith (interim chief executive officer), 2001

Paul G. Vallas, 2002-7

Arlene C. Ackerman, 2008-11

Leroy D. Nunnery (interim chief executive officer), 2011-12

William R. Hite, Jr., 2012-22

Tony Watlington, appointed 2022

William W. Cutler III is Professor Emeritus of History at Temple University whose research and teaching focus on the relationships between education and American Culture. His books include Parents and Schools: The 150-Year Struggle for Control in American Education (University of Chicago Press, 2000).

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Two North Philly grade schools to undergo massive staffing changes in hopes of 'turnaround' (WHYY, March 11, 2014)

- Philly principals ratify contract deal that includes significant salary and health care concessions (WHYY, March 17, 2014)

- Schools funding a big unanswered question in Philly budget hearings (WHYY, April 1, 2014)

- Philly teachers create website to document district's budget crisis (WHYY, April 14, 2014)

- 'Election season' in North Philly: parents hear pitches on charter conversion (WHYY, April 16, 2014)

- Beyond "doomsday": Philadelphia School District unveils its "empty shell" budget (WHYY, April 26, 2014)

- Philly Parking Authority seeks rate hike for city meters -- with proceeds destined for schools (WHYY, April 28, 2014)

- North Philly parents suspicious of postponed charter school election (WHYY, April 29, 2014)

- School district officials come to Philly Council in quest for funds (WHYY, May 5, 2014)

- Philly School Reform Commission refuses to adopt 'empty shell' budget (WHYY, May 29, 2014)

- Councilman wants to take a chance on 50-50 drawing for Philly schools (WHYY, June 8, 2014)

- Philly Futures helps college-bound Northeast High student defy expectations, odds (WHYY, June 10, 2014)

- Superintendent Hite: Pa. not providing Philly kids a 'thorough and efficient' education (WHYY, June 24, 2014)

- Philly Mayor says schools would be in trouble without proposed cigarette tax (WHYY, June 30, 2014)

- Philly parents anxiously await school funding -- or dire decision by district (WHYY, August 8, 2014)

- Students left on corner as Philly district reduces busing service (WHYY, August 18, 2014)

- Woes of Philly schools can't be overstated, Hughes declares (WHYY, August 21, 2014)

- A Philly first: No schools on the Pa.'s 'persistently dangerous' list (WHYY, September 3, 2014)

- Scenes from the first day of school in NW Philadelphia [gallery] (WHYY, September 8, 2014)

- Fallout of Pa. cheating scandal continues with charges against two Philly principals (WHYY, September 26, 2014)

- Beers, bars and babies: The next generation of Philly school parents gets serious (WHYY, November 20, 2014)

- Philly schools adopt five-year plan with minimal 'ask' of $30 million (WHYY, December 19, 2014)

- Eighth Philly educator charged in standardized test cheating scandal (WHYY, January 7, 2015)

- Contentious debate over Philly charter expansion comes to a head Wednesday (WHYY, February 18, 2015)

- How is special education paid for in Pennsylvania public schools? (WHYY, April, 29, 2015)

- Phila. School District passes an austere — but hopeful — budget (WHYY, July 1, 2015)

- Beyond burnout: One teacher's trip back into the classroom (WHYY, August 4, 2015)

- Philly schools don't bite on plans to outsource student health services (WHYY, October 22, 2015)

- Philly schools chief says cash will run out by end of January (WHYY, December 16, 2015)

- Philly SRC votes to phase out two middle schools, not close immediately (WHYY, February 19, 2016)

- Liquor-by-the-drink tax generates $60 million for Philly schools, revenue chief says (WHYY, June 3, 2016)

- Despite progress, teacher vacancies linger as Philly schools open (WHYY, Spetember 7, 2016)

- Area near Drexel in West Philly wins big school grant (WHYY, December 22, 2016)

- Report: Philly needs billions to rehab sagging schools (WHYY, January 27, 2017)

- Philly SRC departs with busy meeting (WHYY, June 22, 2018)

- At first meeting, new Philly school board turns to old hand for leadership (WHYY, July 10, 2018)

- What happened when City Council met the new Philly school board for the first time (WHYY, November 27, 2018)

- What happened when Philly closed 30 schools? New study offers answers (WHYY, March 19, 2019)

- Philly school board names Tony Watlington as new superintendent (WHYY, April 1, 2022)

- Philly school district elects 'new generation of leaders' (WHYY, December 16, 2022)

Links

- School District of Philadelphia

- The Philadelphia Public School Notebook

- James A. MacAlister, Manual Training in the Public Schools of Philadelphia (1889, Google E-Book)

- PhilaPlace: Central High School

- PhilaPlace: The Philadelphia High School for Girls

- Education in Pennsylvania (ExplorePAHistory)

- Working the Public School System (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)

- Schools Interrupted (YouTube, film by Dalena Bui and Danielle Little of Science Leadership Academy)