Red Arrow Lines

Essay

The Red Arrow Lines of the Philadelphia Suburban Transportation Company (1936-70) became a national model and local brand of marketable mass transit in the 1950s, when few private companies still built, managed, owned, and operated suburban public transportation services, let alone profited from them. At a time when motor-vehicle commuting forced most transit proprietors into bankruptcy, receivership, or acquisition, the Red Arrow Lines–high-speed railways, trolleys, and electrified and diesel buses operated west and south of Philadelphia by Merritt H. Taylor Jr. (1922-2010) and his family of transit managers–outlasted and outshined most national and local competition.

Paradoxically, the Philadelphia Suburban Transportation Company cultivated loyal ridership of Red Arrow Lines by curtailing services and closing stations it acquired in 1946 from the beleaguered Philadelphia & Western (P&W) railroad and bus company run by A. Merritt Taylor (1874-1937), Merritt H. Taylor Jr.’s grandfather. Over the next decade, Taylor Jr. reduced train services and servicemen from sparsely populated industrial centers of Chester County, Pennsylvania, like Strafford and West Chester, and added trackless trolleys (powered by overhead wires) and diesel-fueled buses better able to navigate the sprawling towns of Montgomery County such as Ardmore and Haverford. Gut renovations of Red Arrow-related real estate in Montgomery and Delaware Counties, including the profitable Norristown High-Speed Line’s Terminals on Sixty-Ninth Street in Upper Darby, Delaware County, and on Main Street in Norristown, made room for back-office operations once assigned to branch offices. The redesign of these Art Deco structures left them without amenities like restaurants, lunch counters, and barber shops, but postwar residents of Philadelphia suburbs patronized Red Arrow Lines regularly enough to support expansion of the Philadelphia Suburban Transportation Company into New Jersey.

The lean architecture and infrastructure of Red Arrow Lines included a few luxuries that became the Taylor family legacy. Before aerodynamically-designed Silverliner trains graced commuter rail lines of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company in 1963, the Red Arrow Lines boasted “bullet trains”—sleek, bullet-shaped rapid transit cars of early modernist style that picked up and discharged passengers every fifteen minutes, every hour of the day, along the 13.7-mile long Norristown High-Speed Line. These Liberty Liner trains featured vibration dampers and waitstaff, which allowed coffee and tea service during the morning rush hour and beer and wine during the evening rush hour. Less-equipped buses and trolleys earned repeat ridership by traveling in dedicated traffic lanes leading to the Norristown High-Speed Line, express bus stops of the Schuylkill Valley Lines Inc., and rapid-transit terminals of the Philadelphia Transportation Company, as well as commuter rail stations of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Reading Railroad, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad companies. Together, the styling, synchronized schedules, exclusive rail and road rights, and intermodal connections of the Red Arrow Lines kept the company in business, in the pages of industry periodicals such as Railway Age, and in popular television shows like 60 Minutes.

The financial success of the Red Arrow Lines in the 1950s contributed to Merritt Taylor Jr.’s decision to abstain from participating in the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Compact (SEPACT) formed by Philadelphia and four surrounding counties in 1961. Taylor, an active member of Delaware County’s conservative-leaning political organizations, eschewed public subsidies for replacing rolling stock and denounced public-private partnerships in real estate reinvestment throughout his twenty-four-year tenure as Red Arrow Lines’ president. Meanwhile, competitors of the Red Arrow Lines—the Pennsylvania Railroad, Reading Railroad, and the Philadelphia Transportation Company, a local subsidiary of National City Lines Inc.—capitalized on the availability of public funds to cover their ballooning debts and compensate for their reduced ridership. Between 1958 and 1970, Taylor refused to redirect Red Arrow buses and trolleys to commuter rail stations in Media or otherwise participate in projects by SEPACT or SEPTA (the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, formed in 1963) to decrease street traffic and offer discounted direct rail service from the suburbs to Philadelphia’s business district.

Taylor’s reticence to join government-business compacts of the 1960s preserved his family’s political alliances in Delaware County, which also opted out of regional transportation compacts orchestrated by Philadelphia’s metropolitan-minded mayors. At the same time, however, the Red Arrow Lines lost revenue to Philadelphia and Montgomery County, which charged the company ever-higher tariffs to use their tunnels, terminals, streets and bridges. Rather than wait until it could no longer compete against the rail ridership recruitment and retention programs of local, state, and federal transportation authorities, Red Arrow leadership elected in 1970 to resell their stake in P&W to SEPTA at a premium of $13.5 million.

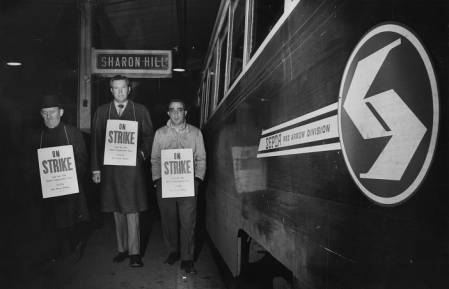

Red Arrow-decorated trains, trolleys, and buses rolled into Upper Darby terminal of the Norristown High-Speed Line for the first time under SEPTA leadership on January 29, 1970. Although authorized by the Taylor family, SEPTA’s takeover of Red Arrow Lines sparked a strike lasting more than a month by Red Arrow employees, many of whom had supported the Taylor family’s sustained opposition to public management, subsidies, and regulation. SEPTA conceded only temporarily to one of their most expensive demands—retention of the Red Arrow workforce that operated, maintained, cleaned, and stocked the luxurious Liberty Liners. Seven years after SEPTA adopted the Red Arrow legacy and logo, it abandoned them to address pressing problems with service delivery, facilities management, and systems integration throughout southeastern Pennsylvania.

As SEPTA reduced the Red Arrow Lines to essential sites and services, SEPTA’s Red Arrow Division grew under its first director, Ronald DeGraw (1942-2006), to include the community-based organizations and anchor institutions that restored or repurposed Red Arrow real estate at SEPTA’s behest. Universities, historical societies, and neighborhood and business associations of Montgomery and Delaware Counties such as the Lower Merion Civic Council and Swarthmore College adapted abandoned rail stations to commercial and civic uses. They converted railways to greenways and sponsored transit services such as shuttles to connect new shopping centers with old Red Arrow stations that had survived budget cuts and abandonment in the early 1980s. Later known as “railbanking,” such nongovernmental efforts to keep Red Arrow infrastructure and architecture in public use enabled SEPTA, their state sponsor, to retain ownership of land that the Taylor family amassed and reserve the right to reuse or redevelop this real estate at a later date. By the end of the 1980s, SEPTA began to reinstate suburban transit routes and services in sprawling towns that the Philadelphia Suburban Transportation Company once served. With each reactivation of a Red Arrow right-of-way, the landscape of private enterprise once again became integral to public transportation provision in Greater Philadelphia.

Fallon Samuels Aidoo, Ph.D., a transportation and land use planning practitioner, scholar, and educator, advises designers, managers, and sustainers of transportation services and spaces–from streets and shuttles to terminals and trails. She is co-author of the Newark River Access Guide (2013), a resource for reinvestment in transportation to and along the Newark, New Jersey, riverfront right-of-way, and co-editor of Spatializing Politics: Essays on Politics and Place (Harvard University Press / Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 2016), analyses of architecture and urbanism that shed light on contemporary political conflicts and consensus. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Philadelphia Suburban Transportation Co. Red Arrow Lines (Market Street Railway website)

- Phillytrolley.org

- Red Arrow Lines (Pennsylvania Trolley Museum)

- Red Arrow Lines -- Cars on the Ardmore Line (YouTube, July 2, 2011)

- Philadelphia Suburban (Red Arrow) trolley car 80 (YouTube, June 15, 2014)

- Philadelphia Suburban Transit Company (Social Networks and Archival Context Project, University of Virginia)