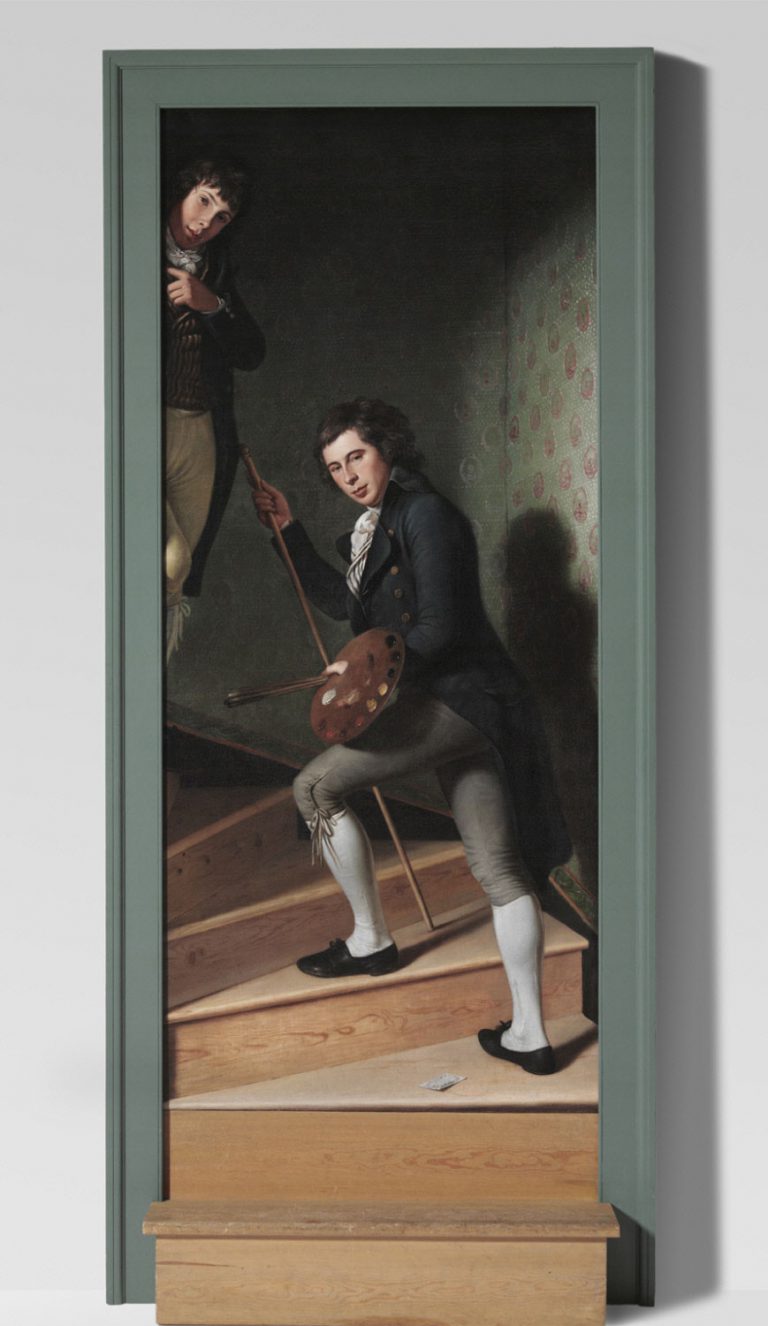

Staircase Group (The)

Essay

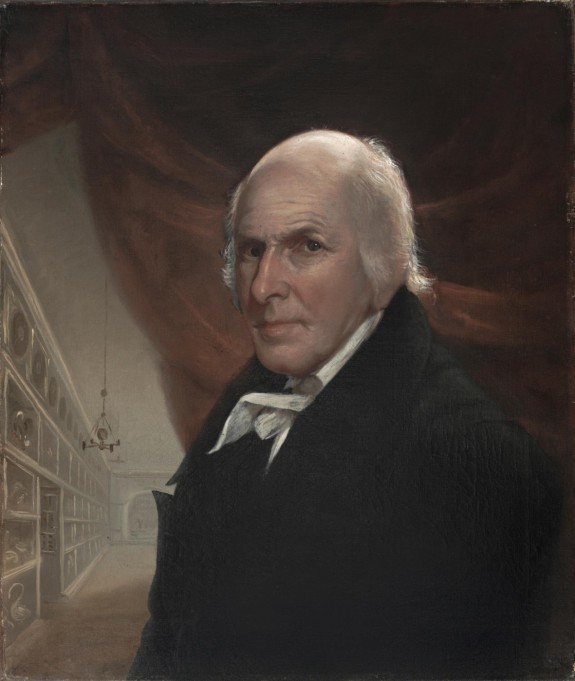

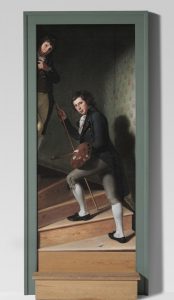

After Charles Willson Peale’s The Staircase Group emerged from a private collection in the mid-twentieth century, the Philadelphia Museum of Art placed the compelling trompe l’oeil (deceive the eye) double portrait on display and it became widely reproduced in American popular and art historical literature. Its contemporary popularity echoed the popularity it enjoyed at Peale’s Philadelphia Museum (1786-1854) between its creation in 1795 and 1854 when the museum’s financial failure forced the sale of its painting collection.

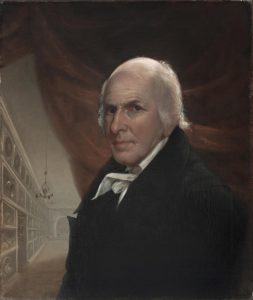

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) was among the most notable portrait painters of revolutionary and federal Philadelphia and the innovative founder of America’s first museum created to educate and entertain the public through lectures, demonstrations, and carefully presented collections of art and natural science. His Staircase Group shows two of his sons, Raphaelle (1774-1825) and Titian Ramsay (1780-98), in that museum, as indicated by the admission ticket seen on the step near Raphaelle’s foot. Both sons were an integral part of this enterprise and Raphaelle, shown palette in hand, assisted his father while honing his skills in portraiture and the still life painting for which he is now famous. His younger brother, Titian, was admired for his expertise in natural science, developed while working on the museum’s collections. Although Titian died four years after the portrait was painted, his namesake, Titian Ramsay (1799-1885), carried on this tradition as a notable explorer and naturalist.

Visitors recorded seeing it installed in a doorframe with a real stair beneath it to reinforce its illusionism. According to Raphaelle and Titian’s brother, Rembrandt (1778-1860), President George Washington (1732-99), whom Charles painted from life seven times, mistook the highly illusionistic picture for the young men themselves, while visiting the museum to see life-size wax figures of Native Americans in authentic dress. For Charles Willson Peale this picture exhibited his ability as a portraitist and his technical expertise in making pictures calculated to impress and entertain the public.

Trompe l’oeil paintings, drawings, and wax figures enjoyed international popularity at this period. Such works teased viewers perceptions, either delighting them when they were surprised by an illusion or awakening them to greater vigilance about accepting what they saw “at first glance.” As art historian Wendy Bellion observed, the popularity of such illusionistic pieces in Philadelphia at this time may have reminded citizens to maintain a healthy skepticism about the activities of their government, not just its public pronouncements.

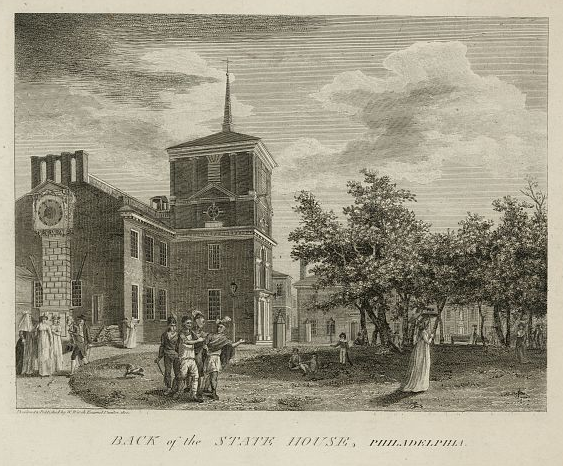

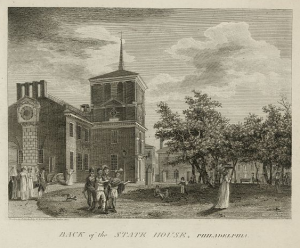

In 1795 Peale’s Museum was located in Philosophical Hall, the home of the American Philosophical Society, founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1743 “to promote useful knowledge.” Positioned on the east side of the State House, it was at the center of the sophisticated social, political, and cultural life of Philadelphia when it served as the U.S. capital. Prior to its installation in the museum, The Staircase Group was shown at the inaugural exhibition of the Columbianum (May-July 1795), America’s first, short-lived art academy that Charles was instrumental in founding. Here modest and accomplished work by a variety of artists was seen alongside sophisticated large scale portraits by famous American-born artists John Singleton Copley (1738-1815), Joseph Wright (1756-93), and Benjamin West (1738-1820), then the second president of Britain’s Royal Academy of Arts. It was with these artists Peale wished to compete and the picture he identified as Portraits of two of his Sons on a stair case was conceived within the artistic tradition he learned while studying with West in London from 1767-69.

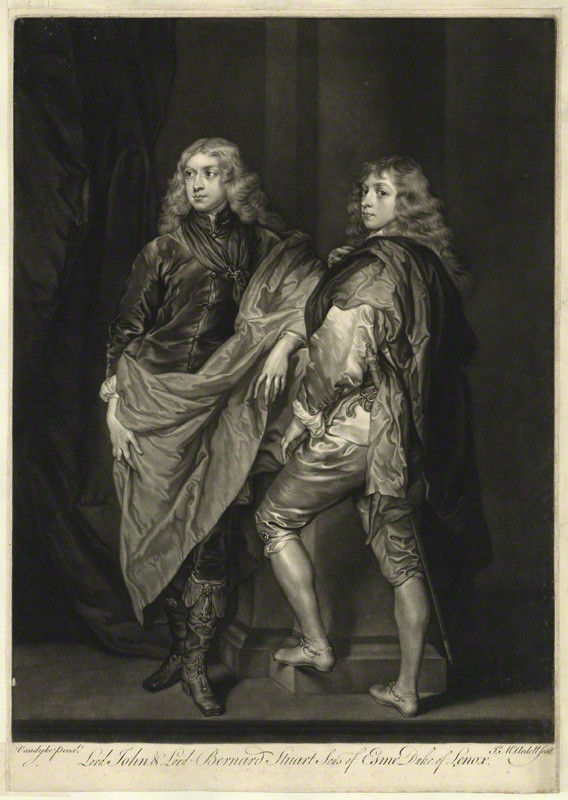

This academic tradition, which Peale followed in his most ambitious portraits, directed artists to improvise on the work of an accomplished artist. This provided a template for a composition and often provided sentimental or intellectual associations relevant to the new picture. These enriching pictorial references impressed educated viewers with an artist’s understanding of the great art of the past and raised his status among his peers. Famous works were available through engravings of which Peale had a large collection.

The celebrated picture Peale referenced in his Sons on a Staircase was Lord John Stuart with his brother, Lord Bernard Stuart, painted by Europe’s most admired portraitist, Sir Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641), the namesake of Peale’s infant son, who had died in 1794. This reference highlighted the contrast between siblings of the hereditary British aristocracy and those of America’s new democracy. As Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), then president of the Peale Museum’s board, believed, America had a “natural aristocracy” defined by “virtue and talents” rather than privilege and “this was the most precious gift of nature, for the instruction, the trusts, and government of society.” Engaged, rather than relaxed like Van Dyck’s young noblemen, Peale’s sons, Raphaelle and Titian–Nature’s young noblemen–actively welcome visitors into their family’s museum, an enlightened enterprise their artist-patriot-entrepreneur father, Charles Willson Peale, deeply believed would serve their new nation.

Carol Eaton Soltis is Project Associate Curator, Peale Collection Catalogue, American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University