Telegraphy

By Lucy Davis

Essay

Telegraphy transformed communication in the nineteenth century, allowing information to travel nearly instantly across the nation and the world. Developing alongside railroad transportation, the telegraph bridged the distance between Philadelphia and cities across the globe.

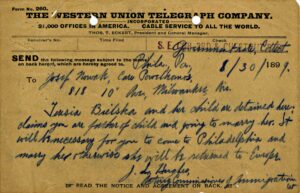

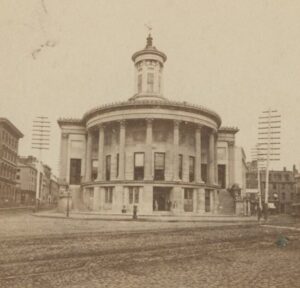

The earliest telegraph systems were devised in the 1790s in France and consisted of a line of towers on which an operator could broadcast signals, similar to flag semaphore. The short range and great expense of constructing and operating these optical telegraphs limited their application to major government projects. Many people worked on the development of the electric telegraph, but the cumbersome systems found little support until Samuel Morse (1791-1872) devised a “bi-signal” system of long and short current bursts to represent individual characters, along with a receiver that recorded the transmission automatically on paper tape to allow translation. Morse Code became the de facto cypher used in telegraphic communications. Morse and a partner, Alfred Vail (1807-59), built their first experimental telegraph device at the Speedwell Ironworks in Morristown, New Jersey. On February 8, 1838, the pair demonstrated the system to a scientific committee at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia.

The First Connection

Philadelphia’s location between other major cities on the Eastern Seaboard made it a prime location for an early telegraph system. Service began in June 1846, when the Magnetic Telegraph Company connected the city to New York City and later to Baltimore and Washington, D.C. Publisher William M. Swain (1809-68) of the Philadelphia Public Ledger and the Baltimore Sun, realizing the utility of the device for transmitting news quickly, raised over a third of the $10,000 capital required for the southern line. This line allowed the Ledger and the Sun to report dispatches from the Mexican-American War. During the American Civil War, Philadelphia newspapers used the telegraph to provide same-day updates on the Battle of Gettysburg. The technology also proved invaluable for emergency services. By 1856, Philadelphia had installed a municipal services telegraph system connecting police and fire stations across the city to create a rapid response network.

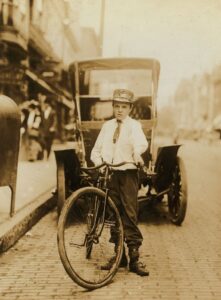

Telegraph lines often paralleled new railroad lines, which expanded rapidly during the same period. The two services allowed both people and information to be transported rapidly across the vast expanses of the nation. When the transcontinental railroad connected the West to the existing rail network in the East in 1869, a telegraph line was built along it. A Transatlantic line—the third attempt at connecting Europe and North America—began operation in 1866, allowing news and messages to be transmitted across the western world. Consolidation followed as small regional networks were purchased by large companies like Western Union, which held a near-monopoly in the United States by the turn of the twentieth century.

Arrival of Wireless

Wireless telegraphy eliminated the need for expensive cables by transmitting messages using radio waves. The first wireless telegraphy company in the nation, the American Wireless Telephone and Telegraph Company, transmitted its first message in 1900 between Camden, New Jersey, and Philadelphia. As proof of the technology’s ability to traverse much greater distances, the DeForest Wireless Telegraph Company built a wireless telegraphy station within the headquarters of the Philadelphia-based North American at 121 S. Broad Street. The newspaper almost instantly received and published the March 1905 inaugural address of President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919). Wireless telegraphy became an invaluable tool during World War I by allowing instantaneous communication with troops in the field, the air, and the sea, but its use declined soon after.

The introduction of the telephone at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition heralded the end of telegraphy, as the new technology gradually replaced text-based messaging for many daily uses. During World War II, the military used telegraphs to inform next-of-kin of war deaths. Telegraphy remained in limited use due to the high cost of long-distance telephone calls until the internet and satellite communications rendered the format obsolete in the late 1990s. Although amateur radio operators kept wireless telegraphy alive into the twenty-first century, the communication medium otherwise came to an end in 2006, when Western Union carried the last telegram in the United States.

Lucy Davis is an independent public history consultant in South Jersey. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2024, Rutgers University.