U.S. Supreme Court

By Laura Michel

Essay

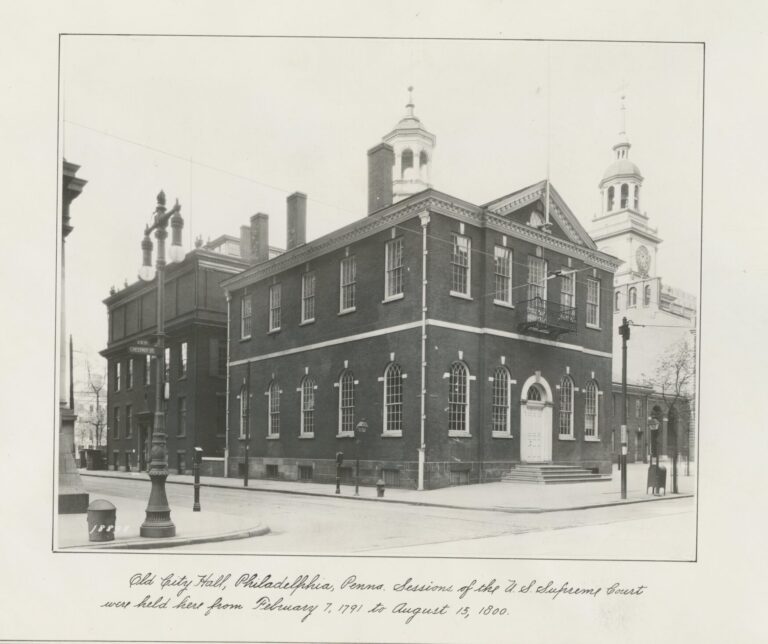

As the nation’s capital from 1790 to 1800, Philadelphia also served as the seat of the United States Supreme Court. Sharing a space with the Mayor’s Court in Old City Hall at Fifth and Chestnut Streets, the Supreme Court of the 1790s was very much an institution in progress. Established by Article Three of the Constitution and further elaborated by the Judiciary Act of 1789, the court’s power of judicial review—generally considered to be at the heart of the institution’s authority and prestige—was not specifically articulated until Marbury v. Madison in 1803, after the capital moved to Washington, D.C. Despite its relative weakness, scholars have come to identify the Supreme Court’s time in Philadelphia as a period of important procedural groundwork that allowed the court to evolve into an independent and powerful branch of government.

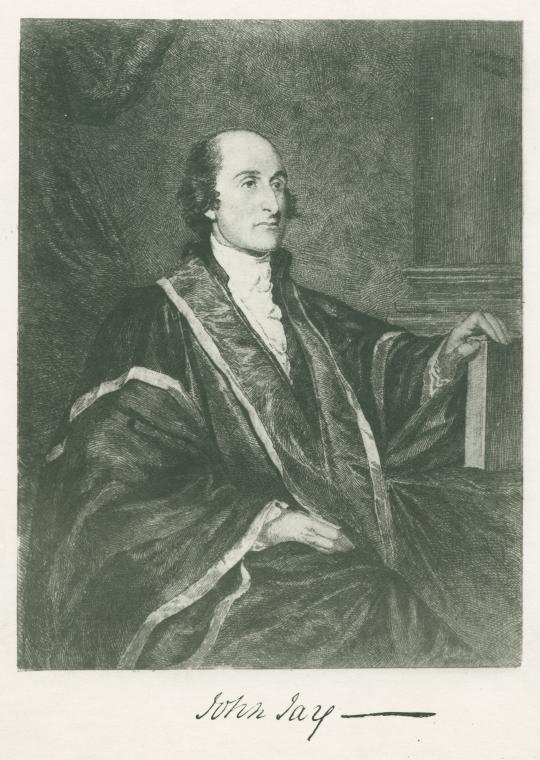

The Supreme Court of the 1790s was smaller than its modern iteration. In accordance with the Judiciary Act of 1789, it had six members: one chief justice and five associate justices. With a firm belief in the importance of a strong judiciary to effective governance, President George Washington (1732-99) approached the selection of these early justices deliberately, prioritizing geographic diversity and jurists with established records of service to the young nation. The men who served during the court’s first terms in Philadelphia included well-known figures such as Federalist Papers coauthor John Jay (1745-1829); Constitutional Convention delegates James Iredell (1749-1829, North Carolina), John Rutledge (1739-1800, South Carolina), and James Wilson (1743-98, Pennsylvania); as well as established jurists William Cushing (1732-1810) from the Massachusetts Superior Court and John Blair (1732-1800) of the Virginia Court of Appeals. During the court’s tenure in Philadelphia, six additional appointments were made, including the third chief justice, Oliver Ellsworth (1745–1807).

The justices met as a whole body for two one-month terms in February and August and spent much of their time away from Philadelphia performing their “circuit riding” duties. The Judiciary Act of 1789 had established a series of lower federal courts: one district court per state and three superior circuits (Eastern, Middle, and Southern). Drawing from English judicial tradition, two Supreme Court justices were assigned to each “circuit” and would “ride” to hear cases in their respective regions. The justices almost universally loathed these duties. While neither February nor August was the most salubrious time to be in Philadelphia, circuit riding presented much more of a threat to life and limb. Justice Iredell’s leg was broken in a road accident, Justice Samuel Chase (1741-1811) nearly drowned when his carriage misjudged the depth of a river, and Justice Wilson died of malaria while on circuit duties in North Carolina. While the Judiciary Act of 1793 reduced this burden and required only one justice to be present at a hearing, the practice of circuit riding meant that justices were not part of the everyday social or political life of Philadelphia in the 1790s.

Constrained by the burden of circuit riding and its as-yet unsettled powers, the Supreme Court heard only an average of seven cases per year during its time in Philadelphia. While few, these cases nevertheless reflected the role of the court in the broader Federalist project of establishing and enhancing federal authority. Van Staphorst v. Maryland (1791), the first case docketed before the Supreme Court, involved a dispute over the repayment of a loan made by Dutch bankers Nicolaas (1742-1802) and Jacob van Staphorst (1747-1812) to Maryland during the Revolution. While it was ultimately settled out of court, by agreeing to hear the case, the court held that it had jurisdiction to enforce contracts made between foreign nationals and states.

Subsequent cases continued to build on this articulation of federal power and authority, perhaps most controversially in Chisholm v. Georgia (1793). In this landmark case, Alexander Chisholm (c. 1738-1810), executor of the estate of a South Carolina merchant, sued the state of Georgia for the nonpayment of goods provided by his client during the Revolutionary War. Georgia, citing the long-held British common law doctrine of sovereign immunity, claimed that a state could not be sued without its consent and called for the case to be dismissed. In a 4-1 decision in favor of Chisholm, the court ruled that Article 3, Section 2, of the Constitution superseded states’ claims of sovereign immunity and made them subject to the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. With the ratification of the Constitution, Chief Justice Jay wrote in his decision, the ultimate sovereignty of the people was placed in the federal government, to which the states were subordinate. In the context of the emerging First Party System and debates over federalism, the decision met with vocal opposition, particularly from the states. In response, Congress moved quickly to adopt the Eleventh Amendment (1795), which limited the ability of individuals to sue states in federal courts. Despite this apparent setback, the Supreme Court continued to place limits on states’ sovereignty throughout the 1790s, including in Ware v. Hylton (1796), which ruled that federal treaties had precedence over any conflicting state laws.

In addition to cases heard, the court fashioned its place in the federal system in what it opted not to do. Rather than defer to the stronger and better-defined executive and legislative branches, the justices asserted their own vision of the extent and limits of judicial power. This was particularly apparent in the career of John Jay, the first chief justice of the Supreme Court. In 1793, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826)—acting on behalf of Jay’s longtime friend President Washington—asked the court to prepare an official advisory opinion related to American neutrality amidst ongoing conflict between Britain and France during the wars of the French Revolution. Jay, who was well-known and respected for his role in the negotiation of the Treaty of Paris, was certainly qualified to advise on this matter of foreign policy. Nevertheless, he declined to offer an official opinion in order to protect the impartiality of the Supreme Court should any related cases appear on its docket in the future. Only by doing so, Jay asserted, could the separation of powers and system of checks and balances established by the Constitution truly succeed. At the same time, Jay saw no issue with continuing to serve as a personal advisor to Washington. He even offered to help the administration draft its 1793 Proclamation of Neutrality, publicly defended the policy in an ex-officio capacity, and led a diplomatic mission to Britain to negotiate what became known as the Jay Treaty in 1794.

In terms of the accepted scope of its authority, prestige, the amount of time spent in session, and the number of decisions made, the Supreme Court of the 1790s was a less powerful and less robust institution than the court that later emerged in Washington under the leadership of Chief Justice John Marshall (1755-1835). Nevertheless, the importance of the court’s evolution during its time in Philadelphia should not be underestimated. Its role in the articulation of federal supremacy and its assertion of its position as an independent third branch of government laid the groundwork for its emergence in later years as a powerful and prestigious institution.

Laura Michel holds a Ph.D. in History from Rutgers University. Her work considers the intersection of philanthropy, reform, and identity in the early American republic. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2023, Rutgers University.