Baseball: Negro Leagues

By Neil Lanctot | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

More than any other city, Philadelphia epitomized the significance of Negro League baseball in urban communities. For a remarkable eight decades, local fans consistently supported a series of Black ball clubs whose successes generated racial pride and represented a triumph of African American institution-building.

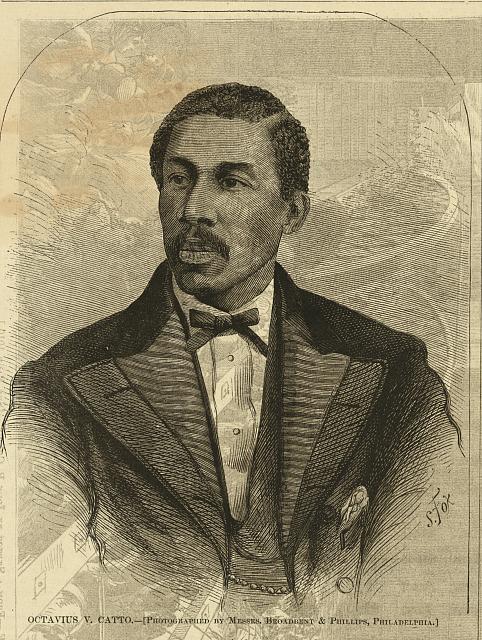

In Philadelphia, the first all-Black baseball teams surfaced in the 1860s. By far the most prominent was the amateur Pythian Club, which not only scheduled games against several white opponents but also unsuccessfully attempted to affiliate with the National Association of Base Ball Players, the major baseball organization of the era. Although the assassination of Octavius V. Catto (1839-71), the club’s driving force and local Black leader, brought the Pythians’ story to a premature close, other organizations emerged to take their place. The mid-Atlantic-based Cuban Giants, considered to be the first Black professional team, debuted in 1885 and was heavily comprised of Philadelphia amateur players. Initially perceived as a gimmick (the players spoke a sort of mock-Spanish to pass as Cuban), the Cuban Giants soon had fans buzzing about their exceptional talents on the field. To survive, the team took on any and all comers, rambling up and down the East Coast in search of profitable games.

In the years that followed, the Cuban Giants regularly visited Philadelphia, an especially attractive venue thanks to its thriving semiprofessional baseball scene and large Black population. But local African Americans had no hometown professional team to support until the formation of the Philadelphia Giants in 1902. Like other Black clubs, the Giants spent a good deal of time on the road, although they sometimes rented Columbia Park, the Athletics’ home field at Twenty-Ninth and Columbia Streets.

Rise of the Hilldale Club

The Philadelphia Giants were a success on the diamond but not at the box office and finally disbanded in 1911. In the meantime, a group of Black teenagers established the Hilldale Club, an amateur team playing in an “open field” in Darby southwest of the city. With dozens, if not hundreds, of similar squads organizing and folding each season, no one foresaw that Hilldale would one day become a major Black institution.

The man behind the Hilldale miracle was a gentlemanly little postal clerk named Edward Bolden (1881-1950), who began as the team’s scorer but soon took control of the young club. Over the next several years, Bolden heavily publicized the team in the pages of the Black weekly Philadelphia Tribune, rented home grounds at Chester and Cedar Avenue in Darby, and aggressively recruited the best local players. Their following grew so rapidly that Bolden and a group of fellow postal employees incorporated the team in 1916 with plans to move to an all-salaried roster the following season.

As a full-fledged professional team, Hilldale (also known as the Daisies) became one of the most successful Black ballclubs in the country in the 1920s. The thousands of rural Black southerners pouring into the Philadelphia region as part of the Great Migration further expanded Bolden’s already sizable customer base, which eagerly turned out for Hilldale’s regular Saturday home games in Darby (Pennsylvania blue laws prevented Sunday baseball until 1934). Strong white semiprofessional teams, often sponsored by business and industrial concerns such as Lit Brothers, Strawbridge and Clothier, and Fleisher Yarn, provided additional revenue. Flush with cash, Bolden signed nationally known superstars such as catcher Louis Santop, but he always kept his eye out for area talent. Future Baseball Hall of Fame third baseman Judy Johnson was a product of the Wilmington sandlots, while infielder Billy Yancey got his start on the fields of South Philadelphia.

The post-World War I prosperity of Hilldale and other Black teams led to the formation of the first permanent professional leagues: the Midwest-based Negro National League (NNL) in 1920 and the Bolden-backed Eastern Colored League (ECL) in 1922. Not surprisingly, Hilldale captured the ECL’s first three pennants and participated in the Negro Leagues’ first World Series in 1924. Although beaten by the Kansas City Monarchs five games to four, Hilldale got the better of the rematch in 1925, taking the deciding game at Phillies Park (later known as the Baker Bowl) at Broad and Lehigh Streets.

The Depression Takes a Toll

Bolden had built a tremendous ballclub, good enough to beat a barnstorming group of Philadelphia Athletics in five of six games in 1923. But Hilldale struggled to weather the subsequent economic downturn in Black Philadelphia, culminating with the onset of the Great Depression. By 1930, Bolden had departed, soon to be replaced by John Drew, a wealthy Delaware County politician and bus magnate. After watching attendance shrink to less than 200 fans per game, Drew finally pulled the plug on Hilldale in July 1932.

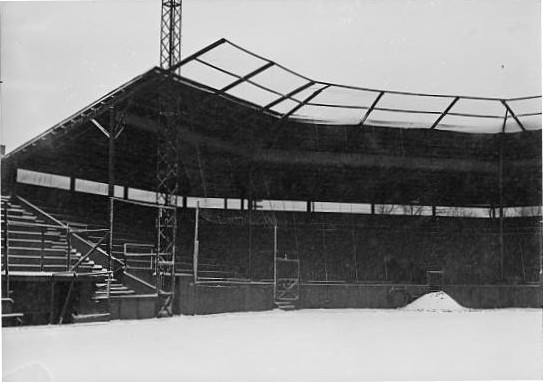

Although the business of Negro League baseball was at its nadir, Bolden returned in 1933 with a new club, the Philadelphia Stars. This time, Bolden brought in financial backing from Eddie Gottlieb (1898-1979), a veteran promoter and key figure in professional basketball, first with the South Philadelphia Hebrew Association and later with the Philadelphia Warriors. Eager to attract the rapidly growing Black population of West Philadelphia, the Stars obtained home grounds at Passon Field at Forty-Eighth and Spruce Streets before moving to Parkside Field at Forty-Fourth and Parkside. The park’s location, adjacent to a Pennsylvania Railroad roundhouse, was hardly ideal for baseball. Trains entering or departing the roundhouse generated heavy smoke, which not only affected visibility but also showered coal dust and soot on unfortunate fans.

In 1934, the Stars joined the now eastern-based Negro National League and won their first and only championship that season. In general, the club was never able to match Hilldale’s dominance of the 1920s, often falling short to the powerhouse Homestead Grays. Still, Black Philadelphians faithfully continued to support the Stars as a vital African American institution, one that provided otherwise unavailable opportunities for a number of elite local athletes. Outfielder Gene Benson attended West Philadelphia High School, infielder Mahlon Duckett and catcher Bill Cash went to Overbrook, while catcher Stanley Glenn starred at John Bartram. But the Stars missed out on the era’s best local Black ballplayer, Nicetown’s Roy Campanella, who eventually signed with the Washington Elite Giants in 1937.

Financially, the Stars reached their peak during the early 1940s, when a booming war economy transformed the previously shaky Negro Leagues into one of the major Black businesses in America. Now able to fill larger venues, Gottlieb and Bolden began to lease Shibe Park, home of the A’s and Phillies, for weekly night games in 1943. Two years later, the Stars drew an impressive 101,818 fans for only nine weeknight dates at Shibe (the Phillies and A’s, meanwhile, drew only 773,020 combined for the entire season).

Integration Dooms the Negro Leagues

The Stars’ prosperity did not last long. The postwar integration of Major League Baseball dealt a crippling blow to the Negro Leagues, worsened in Philadelphia by the abandonment of Parkside Field after 1947 and death of Bolden in 1950. Gottlieb and Bolden’s daughter Hilda briefly attempted to keep the team afloat by selling top players to Organized Baseball, but Black Philadelphians were now far more interested in the Brooklyn Dodgers and other integrated teams. The Stars disbanded after the 1952 season, and Negro League baseball itself collapsed by the early 1960s.

Hilldale Park and Parkside Field are long gone, but the proud history of Negro League baseball in Philadelphia has not been forgotten. Historical markers commemorate both of these ballparks where African Americans congregated in the thousands each week to watch the best Black baseball talent in America.

Neil Lanctot is a historian who has written three books, each reflecting his keen interest in sports and race. His writing has also appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer, Baltimore Sun, and several other journals and anthologies. (Author information current at time of publication)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Pythian Baseball Club Headquarters (PhilaPlace)

- Honoring the Stars (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- African American Baseball In Philadelphia Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Society for American Baseball Research

- Former Philadelphia Stars Negro League player Mahlon Duckett dies at 92 (Philadelphia Inquirer, July 14, 2015)

- Negro League Baseball Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)